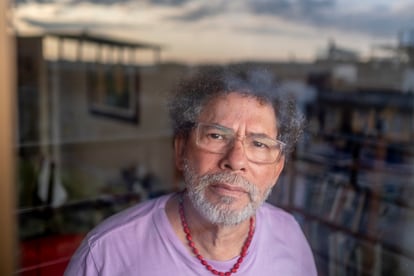

Pastor Alape, the former FARC guerrilla running for town mayor instead of Congress

A member of the organization’s negotiating team in Havana and a former field commander, the 64-year-old is seeking election in his native Puerto Berrío, which EL PAÍS visited during the campaign

Unlike those around him, who have already had two or three beers, Pastor Alape’s glass is still full. He measures each of his sips, stretching them out while the ice cubes melt in the sweltering heat of the night in Puerto Berrío, Antioquia. When asked what he drinks, he answers quietly, “just a splash of rum with water.” He keeps his knitted backpack on and stares at the TV, like everyone else in the corner store. They are watching a World Cup qualifier between Colombia and Ecuador. At the final whistle, people approach him to talk and to complain about insecurity in the town. They ask him to arrange for the return of water supply to a particular neighborhood, or they simply shake his hand. These interactions reveal he is someone special, either because of his past as a guerrilla commander or because of his present as a mayoral candidate for Pacto Histórico (Historic Pact for Colombia), the leftist coalition with which Gustavo Petro won the presidency a year and a half ago.

Alape smokes only at night. He goes out into the street, borrows a lighter, uncaps a pack of menthol Marlboro and enters the realm of sports commentary. “Today we found a way to win. We have good players, although they don’t compare to the roster we had in Brazil,” he notes, referring to the 2014 World Cup, when Colombia reached the quarterfinals for the first time, and he was in his final years in the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). By then he was a member of the FARC secretariat — he had previously commanded two of the organization’s combat blocks, the Magdalena Medio and Noroccidental — and was with his troops in the jungle of Chocó, near the Pacific Ocean. Not wanting to miss any of the games, he hired the services of a cable company and three antennas were installed in the houses of a community in the area. There they watched the 2014 World Cup, hosted by Brazil.

A few meters away, a van from his security detail is waiting for him. He finishes his cigarette and proceeds to say goodbye. It is almost 10 p.m. He coordinates with Mary, his debate leader, over the next day’s schedule and briefly shares with a teacher his proposals for agriculture. “We have to reactivate the entire agrarian and peasant fabric, give Puerto Berrío the capacity to produce its own food. The challenge is to position ourselves as one of the main meat producers in Colombia,” he says.

His silhouette fades as he crosses the street. “I’ll wait for them early. Let me know if they get lost, but the apartment is easy to find,” he says before getting into the truck.

The campaign

Of the 10 candidates for mayor, Pastor Alape is one of those with the least publicity. Aside from a few banners and billboards, donated a couple of weeks ago, his campaign is focused on walking the sidewalks and neighborhoods, talking to the people and showing himself to be different from “the usual politicians.” This tactic exposes him to claims about his past. In July, when he registered his candidacy in the offices of the local registrar, a passer-by shouted at him, asking when he was going to make reparations to the victims. “The mistakes we made served to dehumanize us. The leaders made a mistake by listening to a few, who met in cafés in Bogotá, isolated from reality, and believed that national opinion was favorable. It is not easy to explain what happened in Bojayá or El Nogal,” he acknowledges.

The Bojayá massacre in 2002 and the attack on the El Nogal club in 2003 left 115 civilians dead. They are two of the bloodiest events in the history of the FARC, which in 52 years of clandestine fighting was responsible for 96,952 homicides, according to records from the Colombian Truth Commission, the Human Rights Data Analysis Group and the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP). In 2022, this tribunal, which arose from the agreement between the Colombian government and the guerrillas, charged Alape with deprivation of liberty and hostage-taking. The sentence to be imposed — consisting of community service involving restorative works and other activities — is not yet known, but he is willing to serve it in his village. “We have to generate awareness that transformation is necessary. I am going to pay the restorative penalty here.”

This past has repercussions in the political sphere, but it is impossible to gauge to what extent. In Puerto Berrío, where 25,425 inhabitants are of voting age, there are no polls to measure voting intentions. In the old-fashioned way, the streets are the only way to measure who has a genuine chance of winning. As far as his team are concerned, Alape is one of them. Being the only left-wing candidate, they believe that the 5,122 votes that Gustavo Petro garnered in Puerto Berrío in the second round of the presidential election are a base to grow upon. They agree that the other names with possibilities are Iván Laguna, who has links to the current administration, and former mayors Robinson Baena and Jaime Cañas.

Saray Rúa, 21, is Alape’s campaign manager. She met the former guerrilla at an event for socially reinserted persons and recalls that she was struck by seeing him as “a normal man.” They quickly struck up a friendship and, despite the fear that this relationship initially aroused in Rúa’s family, Alape is now a frequent guest in their home. Rúa is an eighth-semester law student, so Alape prevented him from devoting himself fully to the campaign. “I wanted to cancel classes, but Pastor wouldn’t let me. He insisted that I should continue studying.”

In a café in the urban area of Puerto Berrío, Rúa is accompanied by Salem Arias, another of Alape’s followers and a Historic Pact candidate for the local council. Arias says his father, who always voted to the right and supported former president Álvaro Uribe, now shares posts about Alape’s candidacy on social networks. “We can win or lose, but this is still a historic moment,” he says with the natural enthusiasm of a 20-year-old.

Both explain, in an exercise that one can see they have rehearsed, “the five transformations” proposed by Alape: strengthening productivity, civic culture, sustainable territory, human dignity and the reduction of violence. Paradoxically, at the same time, several shots ring out on the block. A crowd gathers in the street. Everything returns to normal five minutes later, as if nothing has happened.

Life without weapons

The alarm clock is set to go off at 5 a.m. Pastor Alape turns on the radio and starts getting ready. He wears a T-shirt, a necklace of red stones “for energy,” a pair of jeans and closed sandals. His escorts — who spent the night in the neighboring apartment — are still asleep. He squeezes the juice from two grapefruits and makes a coffee from beans sowed by signatories of the peace agreement. From his wooden dining room, he can see the Magdalena River, the same one he sailed when he joined the FARC in December 1979.

On the walls hang half a dozen backpacks, as well as photos and paintings. Highlights include a photograph of Che Guevara, another of the generals of the Mexican Revolution, a copy of Vincent van Gogh’s The Bedroom and an oil painting given to him by a cousin, with the faces of her parents, Lisandro and Ana Fidelia. She was a militant in the Communist Party and was a strong influence in his adolescence. “I got into guerrilla action because of an interview with Camilo Cienfuegos that my mother read aloud.” He stresses that his maternal family, who “descended from black Maroons,” is the reason he has so many relatives in the village. “With the beginning of the pandemic, in 2020, I settled in Puerto Berrío. It has helped me to reconnect with family and friends, who are still here. They tell me that I have a relative on every corner, and we are a very extended family.”

Alape was a member of the FARC negotiating team that signed a peace agreement with the Colombian government in November 2016, during the presidential term of Juan Manuel Santos. Although he was not present at the beginning of the talks in 2012, he joined the delegation two years later and represented the guerrilla group along with Iván Márquez, Jesús Santrich, Pablo Catatumbo, Victoria Sandino, Carlos Antonio Lozada, Marcos Calarcá, Joaquín Gómez and Rodrigo Granda in Havana. Several of them later became congressmen, as a result of the seats granted by the agreement to former guerrillas to participate in national politics. Alape says that he was never interested in becoming a legislator and that he prefers to be mayor of his hometown, where he wants to stay “until his final days.”

He laughingly evokes the soccer rivalry he has with Granda. Alape is a fan of Deportivo Independiente Medellín and Granda of Atlético Nacional, fierce local rivals. “I had enough of him in Cuba. When Nacional won, I knew he would send me a message. I am from Medellín, which is an expression of rebellion,” he says proudly, displaying the collection of jerseys he keeps in his closet.

He is folding the garments when Marlon, who prefers to be called “Chano” — his nom de guerre — enters the apartment. Quiet and shy, a smile escapes from under his cap when asked about his life. He was born in Barranquilla and in his youth joined the FARC. Now, close to 40, he is one of the five ex-combatants that make up Alape’s security detail. He reports that it is time to leave. More bodyguards line up on the steep stairs and the vans park in front of the building. “There goes the old man,” crackles one of the intercoms. Alape comes down slowly, sideways. He explains that he has a bad knee. “I made an appointment with the doctor and they won’t give me an appointment until December,” he complains.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.