Minister Anielle Franco: ‘If I’ve gotten this far, it’s because of Marielle and my mother’

In this interview, the minister of Racial Equality of Brazil and sister of Marielle Franco, murdered five years ago this Tuesday, speaks about women’s representation in politics, racism, the right to abortion and the damage caused by Bolsonaro

Anielle Franco’s life took a radical and unimaginable twist with a murder that took away her only sister and shook Brazil exactly five years ago, on March 14, 2018. Marielle Franco, a charismatic left-wing municipal councillor in Rio de Janeiro with a promising political career, was shot five times. The crime was the work of professionals. She was 38 years old, the current age of her younger sister, who since January has been the country’s minister of Racial Equality. Anielle was a young mother who earned a living as an English teacher at private schools. Prior to that, she was a professional volleyball player, she had two college degrees and lived in the United States. She soon became a public figure in her quest to preserve the memory and the political legacy of her older sister. “If I’ve gotten this far, it’s because of Marielle and my mother,” she says.

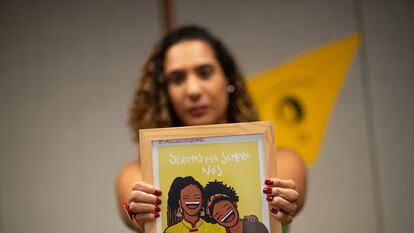

At the entrance of her office and on her work desk, there are a couple of yellow scarves with her face and the caption “Justice for Marielle.” She hopes that the suspects in her sister’s murder, two military policemen who have been in prison for four years, are tried soon. And she especially wants to know who ordered Marielle to be killed.

The minister welcomes EL PAÍS at her office in Brasilia on March 8, International Women’s Day, a date that always had a special meaning at her home. She has just attended the ceremony in which Brazilian President Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva decreed that March 14 shall be the Marielle Franco Day against Race-based and Gender-based Political Violence. “It’s a day that brings some meaning to the efforts [of these years] and it makes the struggle and hard work worthwhile. We still need many more women in politics. Mari [that’s how she refers to her sister] always used to say that her dream was to make it at least 50/50.”

This imposing woman, with a smile on her face and oozing enthusiasm, admits: “We’re still quite far away from that.” Tuesday marks five years (half a decade, she mentions) of her journey from mourning to activism. She is one of the protagonists of the transformative change that democracy is undergoing in Latin America. As Black women raised in a favela in Rio, the Francos embody an impending and apparently unstoppable shift in the power structures of Brazil. People such as these women, who have been excluded for centuries, are breaking into the realm of upper-middle class white men.

Her role as head of the Marielle Franco Institute gave Anielle a level of exposure and recognition that her sister never experienced during her lifetime. After rejecting offers to run for Congress, she accepted the invitation [to become minister of Racial Equality] from the president. “In these five years I was convinced that only something very big would make me change my mind and my life. I’m not talking about money. The return of President Lula to the government after he was in prison, and after six years of misgovernment [the years following the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff], meant a lot to me.” The leader of the Brazilian left was persuasive: “I sat before him, he looked me in the eye and said, ‘You know you have an obligation to accept my invitation’.”

Time magazine just named her one of the 12 Women of the Year. Half a decade ago she picked up where her sister had left off. She left teaching and made it her mission to encourage other Black and mixed-race women to enter politics. “Electing Black women, signing them up as candidates, is not enough – we need to protect them, because there is a question that still haunts me. Why didn’t we realize the huge force that Marielle represented, how could we not see that we needed to protect her? She was unprotected. Nobody ever thought of that, she herself probably never gave it a thought […]. As Angela Davis says, when a woman gets on the move, she shifts the entire social structure, and Mari shifted around many important things.”

Marielle responded fearlessly to the macho attitudes of other politicians, she criticized corruption and police violence, she criticized corrupt congressmen, the power of the mafias of former men in uniform in Rio… And on top of it all, she was bisexual, had a teenage daughter and was married to another women. Anielle herself stirs up some fierce hatred and is often threatened.

Just like female politicians in the rest of the world, Brazilian women come under greater hostility than their male counterparts, whether it be in Parliament or on social media. A study conducted by the Marielle Franco Institute, which was established by her family and led by Anielle until she became minister, showed that over 98% of women candidates in the last municipal elections suffered some form of political violence, and the vast majority of them came under fire on social media. She points out that Black and mixed-race female politicians who were surveyed reported up to “seven or eight types of political violence” and “getting no support from their party.” Bolsonaro and his followers are a pristine example of this strategy of virulent misogyny.

Lula presides over the government with the highest number of women in Brazil’s history, yet only one third of the ministers are women. The situation in Congress is much worse. Women have only 17% of the seats, well below the world average. And only 2% of the members are Black women, even though they make up 28% of the population of the country, where women have been able to vote for the past 90 years.

“White men don’t want to give up those areas of power, but we’re going to take them because we are ready. It’s so good to have the example of Francia Márquez in Colombia!”, she says before underscoring the fact that Lula too has appointed a couple of women to direct two state banks.

In terms of female presence in the political sphere, Brazil pales in comparison to the major countries in the region. Take Mexico, for instance, where 50% of the members of Parliament are women, or Colombia and Argentina (where the vice-presidents are women), or Chile (with a balanced government and a feminist president). She admits that it’s hard for her to accept that “Brazil is such a backward country.”

The Franco sisters were good students. They went to mass on Sundays and danced to funk music. They grew up in a home with strong political views in Maré, one of the largest favelas in Rio de Janeiro. “I grew up as a supporter of Lula, dressing in red. Once my sister and I were chewed out because we lied to our mother and we went into downtown Rio campaigning.” Once she got over it, their mother Marinete was more understanding. Although Marielle always stood out as the political activist while Anielle was fully immersed in volleyball, their political vein is homegrown. “My maternal grandmother and my aunts took action during the dictatorship to protect women,” she recalls.

She says that her mother, a lawyer who on the day of the interview came to visit at the Ministry, used to work as a household employee to pay for her own law studies. A key factor in the minister’s life and career trajectory was the decade or so that she lived in the United States. At the age of 16 she received a scholarship to play volleyball in the US, and her family made every effort to support her move. During her time there, she studied journalism and ethnic and race relations, and she earned the highest salary of her life, according to a recent interview. She was paid 150 dollars per hour to work as a translator for Brazilian immigrants detained in a Texas prison who lacked documentation.

She’ll never forget how different it was to be welcomed in the United States when she returned in February as a minister, alongside Lula, to meet with Joe Biden. “Right then I saw my whole life on a movie reel. Entering the US is so different when you’re not part of the presidential entourage… Back in the day, a dog would sniff you over, at immigration they asked me for my visa, why I was travelling there … And I explained as sweetly as I could that I was going there to study. They even took me for a prostitute!,” she explains.

She took the opportunity to tell the US president that both countries, marked by the legacy of slavery, have a lot of common ground for cooperation. “The problems that they have there, we have them here. There’s George Floyd, there’s Marielle Franco…”

The challenge she is up against as minister of Racial Equality is huge, because Brazil owes a great historical debt to the descendants of the five million Africans who were forcibly taken there over course of three centuries. This debt has everyday consequences for the 56% of Brazilians who are of mixed or Black ancestry. And even more so for the most vulnerable half: the women. She will need to work hand-in-hand with other ministries.

Since she finds it impossible to point out just one priority as the minister, she mentions five lofty issues that complement each other: violence, access to healthcare, hunger (70% of those who go hungry are Black or of mixed race), access to education, university quotas (“I too am the result of quotas”, she often boasts), and access to land, a crucial factor in explaining the historical origin of present-day inequality.

Among the very urgent matters is the issue of violence, she adds. “The first topic we must address is the genocide of Black people. Every four hours a Black person is murdered (…), we’re in the midst of the politics of death, they think we can just be cast aside,” she says. She is well versed in violence, including the one exercised by the Brazilian state. She learned it day in and day out in her neighborhood. “I was fed up with having to step over bodies, of not being able to leave home to study or work, often because of the violence from the State.”

Last week, Maré, the favela where she grew up, went through two days of intensive police operations. The official data are spine-chilling. Last year Brazilian police killed 6,000 people, most of whom were Black. That’s 500 victims a month. For comparison, the US police killed a hundred people each month. The fear that their children won’t return home is a constant concern of black Brazilian mothers. “We need to think of a way to clean up the police so that they understand that, when you go into a favela, there are good, hard-working people there. They can’t just see us as a threat. We need our police to be more race conscious, educated, more humane – not war police.”

Franco wants to address two topics that are gaining momentum in Latin America, but which are still a taboo in Brazil. She is committed to addressing the decriminalization of drugs within the framework of the discussion on public security. Regarding the right to terminate pregnancy, her view is clear: “It’s always the time to discuss abortion, starting with legal abortion.” She thinks the priority today is to guarantee that all Brazilian women, including Black and poor women, who have a higher mortality rate than white women due to clandestine abortion, have access to termination of pregnancy within the public healthcare system in three legal assumptions: rape, risk for the woman’s health and when the fetus has no brain (anencephaly).

Once that’s done, she wants the discussion to be extended to decriminalizing abortion because “it’s the woman’s body. We are tired of having a bunch of men deciding about our bodies.” In spite of the breakthroughs in Latin America, every other day a Brazilian woman dies in a clandestine abortion, and the political environment is extremely hostile, due to widespread conservatism and the power of Evangelical churches across Brazil.

During the final year far right-wing president Bolsonaro was in power, the budget allocated to combating violence against women was the lowest it had been in a decade. That has consequences, as experts underscore. “Physical aggression, sexual offense, psychological abuse have become more frequent in the lives of Brazilian women. Sexual harassment at the workplace, on public transportation, have reached unthinkable heights. And we are facing a sharp increase in the most serious forms of physical violence,” warned a report from the Brazilian Forum on Public Safety.

Two data points are among the most striking: 1,410 Brazilian women were murdered in 2022 just because they were women, nearly four a day; and a million women were attacked with a knife or a fire arms, nearly one of every hundred Brazilian women.

Minister Franco points out that here too the racial inequality stands out: “Violence against Black women is rising while it is declining against white women.” In recent years public policies to fight against this scourge have diminished, she says. Over recent years, much has been said about how former president Bolsonaro rolled back all types of environmental protections, but much less has been said about the damage he inflicted when it comes issues related to race and gender.

“The destruction began with the budget allocations. We started 2023 with just four million Brazilian Reals ($770,000 dollars) for the Ministry of Racial Equality. He hated women and Black people. He ignored figures showing that Black women remained at the bottom in terms of occupation, access to healthcare, to education, but way up on top as far as violence is concerned.”

She points out that the department today is a ministry, but back then it was just a secretariat. But that’s not the only problem. “The people at the helm believed that the issue of race was unimportant. So taking up the task from that point requires restructuring, rebuilding and re-establishing public policy.”

Anielle’s two daughters started school in Brasilia. And the spirit of Marielle is with her every day, she says. She often thinks that the one who should be here is her sister. For instance, when she was interviewed for a famous television program that they grew up watching, or when she became a minister of the government or was included in the list compiled by Time. “When I walk into the Ministry, I think of my sister’s project.”

And where does she think Marielle would be had they not murdered her five years ago? “I’m absolutely sure that she would have become a senator of the Republic, that was her biggest dream.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.