Will China’s next premier be a moderating influence on Xi?

Xi, who has bolstered the state sector, has said that he wants the ruling party to return to its “original mission” as China’s economic, social and cultural leader

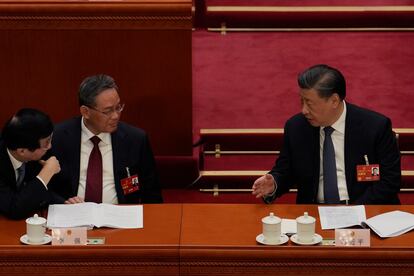

The pro-business track record of the man poised to become China’s top economic official will make his term a test of whether he might moderate President Xi Jinping ‘s tendency to intervene. Li Qiang, 63, who is expected to be chosen China’s premier on Saturday, will have to grapple with a slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy, which is dealing with emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, weak global demand for exports, lingering U.S. tariff hikes, a shrinking workforce and an aging population.

Xi, who has bolstered the state sector, has said that he wants the ruling party to return to its “original mission” as China’s economic, social and cultural leader. That has been accompanied by tighter control over some industries, more aggressive censorship of TV and pop culture and the spread of a “social credit” system that penalizes the public for offenses ranging from fraud to littering. Xi took China’s most powerful role in 2012.

Now, observers are watching whether Li can roll out pragmatic policies during his five-year term. But the process of political decision-making in China is opaque, making analyzing the country’s direction a difficult matter for outsiders.

Expectations are based on Li’s performance as the party chief of the country’s largest city — Shanghai — and as the governor of neighboring Zhejiang province, a hub of small and mid-sized business. And, perhaps more importantly, his close ties with Xi.

Li was quoted as saying in a 2013 interview with respected business magazine Caixin that officials should “put the government’s hands back in place, put away the restless hands, retract the overstretched hands.”

Li hailed Zhejiang’s businessmen as the most valuable resource in the province, pointing to e-commerce billionaire Jack Ma, and he highlighted his government’s cutting red tape.

In contrast, Li has also strictly enforced some state controls, including rules meant to prevent the spread of COVID-19. When his local rule has been out of tune with national policies set by the president and his team, he has eventually fallen into step, seen as key to his rise.

Under President Xi, entrepreneurs have been rattled not just by tighter political controls and anti-COVID curbs but more control over e-commerce and other tech companies. Anti-monopoly and data security crackdowns have wiped billions of dollars off companies’ stock-market value. Beijing is also pressing them to pay for social programs and official initiatives to develop processor chips and other technology.

A native of Zhejiang, Li studied agricultural mechanization and worked his way up the provincial party ranks. In 2003, he started an executive MBA program at Hong Kong Polytechnic University, common among ambitious party cadres.

Priscilla Lau, a former professor of the university and former Hong Kong delegate to China’s legislature, said Li attended her class on Hong Kong’s free-market economy for a chamber in the city and said he recalled her class when they met in Shanghai more than a decade later.

“It shows he’s very diligent,” Lau said.

Li’s working relationship with Xi began in the 2000s when the latter was appointed party chief in Zhejiang. Following Xi’s eventual move to Beijing and appointment as party general secretary, Li was promoted to Zhejiang governor in 2013, the No. 2 role in the provincial government.

Three years later, Li was appointed party chief of Jiangsu province, an economic powerhouse on the east coast of China, marking the first time he held a position outside his home province. In 2017, he was named party boss of Shanghai, a role held by Xi before the president stepped into China’s core leadership roles.

In the commercial hub of Shanghai, Li continued to pursue pro-business policies. In 2018, electric car producer Tesla announced it would build its first factory outside the United States. It broke ground half a year later as the first wholly foreign-owned automaker in China. Even during the strict COVID lockdown in Shanghai last year, the factory managed to resume production after a roughly 20-day suspension, official news agency Xinhua reported.

Tesla vice-president Tao Lin was quoted saying that several government departments had worked almost round-the-clock to help businesses resume work.

“The Shanghai government bent over backwards,” said Tu Le, managing director of Sino Auto Insights, a Beijing-based advisory firm.

On more complicated issues, not everything has been smooth sailing.

Though Li helped shepherd an agreement between Chinese and European companies to produce mRNA vaccines, Beijing was not in favor and the deal was put on hold, said Joerg Wuttke, the president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China.

Before the citywide lockdown, Li appeared to have more leeway to manage the financial hub’s smaller previous outbreaks than most other cities’ leaders did. Rather than sealing districts off, the government implemented limited lockdowns of housing compounds and workplaces.

When the highly contagious Omicron variant hit Shanghai, Li took a moderate approach until the central government stepped in and sealed off the city. The brutal two-month lockdown last spring confined 25 million people to their homes and severely disrupted the economy.

Li was named No. 2 in the ruling Communist Party in October when China’s president broke with past norms and awarded himself a third five-year term as general secretary.

Unlike most of his predecessors, Li has no government experience at the national level, and his reputation was dented by ruthless enforcement of the lengthy COVID-19 lockdown in the financial hub that was criticized as excessive.

His expected appointment appears to indicate that an ability to win the trust of Xi, China’s most powerful figure in decades, is the key determinant when it comes to political advancement.

As premier, Li faces a diminishing role for the State Council, China’s Cabinet, as Xi moves to absorb government powers into party bodies, believing the party should play a greater role in Chinese society. Still, some commentators believe he will be more trusted, and therefore more influential, than his predecessor, who was seen as a rival to Xi, not a protege.

“Xi Jinping does not have to worry about Li Qiang being a separate locus of power,” said Ho Pin, a veteran journalist and Chinese political observer. “Trust between them also allows Li Qiang to work more proactively and share his worries, and he will directly give Xi a lot of information and suggestions.”

Iris Pang, ING’s chief China economist, sees Li mainly as a loyal enforcer of Xi’s will rather than a moderating influence.

Li was pro-business because he was required to be so in his previous government roles, Pang said.

His key trait, she said, is his “strong execution.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.