Cannibalism: The Andes flight disaster, 50 years later

Two survivors of the Uruguayan plane that crashed in the Andes mountains on October 13, 1972 remember the accident that left them stranded in the snow for 72 days and forced them to eat the remains of their dead companions to survive

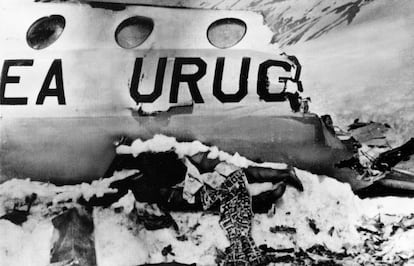

On October 13, 1972, an Uruguayan Air Force plane – carrying a junior rugby team and their family and friends – crashed in the middle of the Andes mountain range. The pilot had confused his position due to poor visibility and, thinking he was descending to land in Santiago, hit the mountains on the border between Chile and Argentina.

The Fairchild Hiller FH-227D – a 50-person American-made aircraft – was carrying 40 passengers and five crew members. After 72 days of freezing conditions, only 16 people survived. The horrors that they had to go through have been the subject of 26 books, nine documentaries and four feature films.

Carlos Páez, 68, was one of the survivors. The Uruguayan is a father and an agricultural technician.

“At that time, we weren’t fighting to get to Hollywood or to be interviewed 50 years later… I was fighting to get back home to be with my mom and dad,” he says in a video call with international media, including EL PAÍS. “I was an 18-year-old boy, the son of a famous painter who gave us everything. I still had a nanny – she packed my suitcase for the trip,” he recalls. “I had never been cold. I had never been hungry. I had never done anything useful. And I lived the most incredible survival story of all time.”

The plane went down in the extreme west of Argentina, about 150 kilometers south of its final destination of Santiago, Chile. It hit the mountains twice, losing its wings and tail. Three crew and eight passengers died on impact.

Eight days after the accident, after failing to find the white plane in the snow, search operations were cancelled: emergency crews would wait for the summer season. At almost 12 thousand feet above sea level, facing a lack of food and the icy fury of the winter wind, another 18 people died while waiting for a rescue that never came.

The 1993 film Alive – the most popular movie made about the tragedy – is, for Páez, an accurate portrait of the days he spent in the snow. Actor John Malkovich plays an adult Páez, narrating the tragedy that changed his life when he was a teenager. The final scene – in which two helicopters arrive at the shell of the plane, where the survivors are sheltering – is described by Malkovich in the simplest way: “Nando and Canessa crossed the Andes and saved us. There isn’t much more I can tell you.”

Survivors Fernando Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa eventually went out to look for help, after hearing on a radio transmitter that the search operation had been cancelled.

“Hearing that they decree you dead, that you are no longer there and that the world goes on without you… removes the dilemma of whether you should wait for a rescue or go for a hike,” recalls Canessa, now a renowned medical doctor. “I left [the wreckage] because I was completely fine. I remember that Arturo Nogueira – who eventually died – told me: ‘how lucky you are, that you have healthy legs and you can go for a walk and save others.’ That gave me a shot of heroism, of hope.”

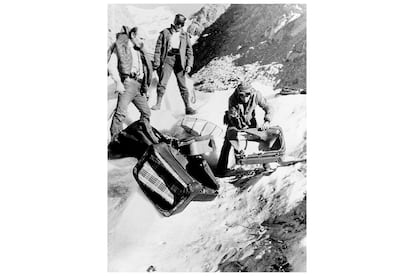

On December 12 – almost exactly two months after the accident – Canessa and Parrado began to climb the mountains to the west. They didn’t know it, but the nearest town was less than 50 miles away. On the ninth day of walking, they came across some cows. At night, from a distance, they saw the owner: a Chilean mule-driver named Sergio Catalán.

“He had seen us before – he thought we were hunting. Since we were carrying trekking poles, he thought they were shotguns. We yelled at him, but he didn’t understand anything,” Canessa explains, as they were too far away. The men wrote a note, tied it to a rock and threw it towards Catalán.

“He told us ‘Tomorrow! Tomorrow!’” Canessa laughs. “It was the most wonderful morning of our lives.”

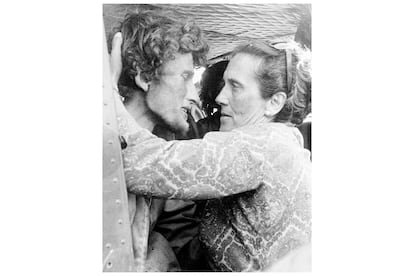

After the rescue operation was finally conducted on December 22, 1972, the surviving group became famous. There were endless invitations to speak, write books and appear on magazine covers.

“At 18, it’s very nice to be famous,” Páez recalls. But his encounter with fame also collided with evil. As the young men returned to Uruguay, a rumor began to spread in Montevideo: that the survivors had killed some members of the group when they began to run out of food. Some decided not to address these attacks. Others, like Páez and Canessa, decided that the best thing was to go out and speak.

“This bothered us because it wasn’t true… it raised doubts in the minds of the families of the boys who died,” Páez told The Washington Post in 1978. “Some magazines said we were cannibals. That’s not true, because [being a cannibal] means killing another person because you like to eat human flesh. We didn’t do that.”

Half-a-century after the tragedy, both still speak openly about how – after several days – they ate some of the remains of fellow passengers.

“Carrying a little bit of our friends in body and soul is an honor that I would have felt if I had died: that they would have used me to live,” Páez says, when he explains how he addresses the subject in his public lectures.

“I usually ask the question backwards: wouldn’t you have done the same? When you go 10 days without eating anything at all, the impossible gets easier.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.