The US-Mexico war against fentanyl: What leaked documents reveal about the joint operation

The massive leak of emails from the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense shows how Mexico’s armed forces and the United States have been exchanging information to stop the trafficking of synthetic drugs

Event 1: One of the drug traffickers is annoyed. One of his lower-ranking officials’ cooks is talking too much about the boss’s operations. “How can a fucking cook dare to talk about what I’m doing?” he complains. The intelligence analyst notes that “cook” refers to those in charge of preparing synthetic drugs, whether fentanyl or methamphetamine. The drug trafficker adds: “You have to be aware of everything happening in your area. Did you send on the report I sent you? Can you imagine what the boss will say if he calls me and I say I don’t have an update on what’s happening?” Amidst the scolding, the subordinate responds that he has to be careful because there are soldiers in the region.

Event 2: a group of lookouts has identified an airplane. The capo in charge orders them to pay attention to their radios to monitor “how the bird enters and exits the area.” The airplane belongs to a faction of the Sinaloa Cartel. It protects drug traffickers and supervises drug deliverers. Event 3: one of the members of the organization asks for a meeting with “the boss.” Event 4: a commander says that he will deliver a shipment of “apparatuses,” a code for long weapons including rifles and anti-armor guns. Event 5: A group of Kaibiles, as the elite units of the Guatemalan army are known, meets with members of the cartel. Reports from the Mexican armed forces suggest that former soldiers train various criminal groups in Mexico.

This is just some of the information that has been gathered by the Mexican armed forces and personnel of the United States Embassy, according to a massive leak of documents from the Mexican Secretariat of National Defense (Sedena), to which EL PAÍS has had access. The leak, which has been attributed to the hacking group called Guacamaya, reveals how Mexico and the United States have been exchanging intelligence to fight against drug trafficking. The documents also confirm that, while Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador may have said that Washington has not been involved in the recent offensives against organized crime, the two countries have been working closely together.

In order to not jeopardize these operations, EL PAÍS has emitted sensitive information about specific targets and monitoring zones. This newspaper sent a press request to Sedena, but it has not yet responded, while the US embassy in Mexico declined to comment.

“[The target] has reports that a mosquito is operating in the area and comments that they will be alert,” reads another leaked document. After intercepting the frequency, the military analyst notes that “mosquito” is a code name for a helicopter.

One of the objectives of the US-Mexico operation is to learn about the hierarchies of criminal organizations and the communications channels they use. This includes decoding the jargon used by drug gangs and how they avoid detection, according to one of the leaked reports. This information, “exclusively for official use,” has been gathered over weeks and passed through several filters, in Mexican and US offices charged with national security and border control. Monitoring drug traffickers is key to revealing the strategies of organized crime and their list of “targets” and locations.

The success of these monitoring operations is measured in drug seizures and arrests. In one such operation, in which almost all the information was communicated in English, over a hundred tons of methamphetamine were seized, along with dozens of tons of chemical used to make synthetic drugs. Two dozen clandestine labs were also dismantled in the operation, which reportedly lasted two years. The operations are mainly focused on fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine.

Health authorities estimate that just two milligrams of fentanyl can be lethal, although the effects vary from person to person. The US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) estimates that a kilo can kill half a million people. By monitoring the cartels, the joint operation between Mexico and the US was able to seize more than 100 kilos of fentanyl. In the US, the opioid crisis continues to be a public health emergency. According to official data, more than 70,000 people died last year from overdosing on synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl. In Mexico, it is a security threat: drug traffickers have realized that they can multiply their earnings with very small shipments of synthetic narcotics, which are easier to hide and sell for higher prices than “traditional” drugs such as cocaine and marijuana.

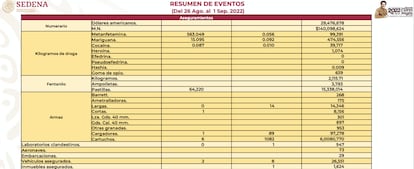

In a leaked document with data until September 1, Sedena reports that more than 15.3 million fentanyl pills were seized during the López Obrador administration, since it began in December 2018. Just in the last week of August, 70,000 fentanyl pills were seized in Tijuana, according to the report, which has a separate column for fentanyl. The last public seizure took place on October 1, when nearly 103,000 pills were impounded in the state of Sonora, which, like Tijuana, is on the US border. Each kilo has a wholesale price of $80,000 and can be sold for $1.6 million once on the street, according to DEA calculations published in The New York Times. The data gives an idea of the scale of the US market: the fentanyl seized by the Mexican armed forces in the last four years would have sold for almost $3.4 billion.

The White House has intensified its war against fentanyl from Mexico, seizing more than 10 million pills in the last four months, officials announced last week. The two main Mexican groups being targeted are also the most powerful: the Sinaloa Cartel and the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. “The most urgent threat to our communities, to our children and our families is these two organizations, which are mass-producing the fentanyl that is poisoning and killing Americans,” said DEA Director Anne Milgram.

The role of US agents in intelligence work in Mexico, either directly or indirectly, has been surrounded in controversy since the so-called war on drugs began nearly two decades ago. In December 2020, the Mexican government passed a National Security law that tightened control over foreign anti-drug agents. That year, a DEA unit, which had been receiving information since the 1990s and which López Obrador accused of being “infiltrated” by criminals, was also shut down. Despite misgivings and conflicts, security remains a central issue in the negotiations between the two countries.

The Sedena leak also include lists of suspicious planes, information on personnel receiving training across the border and manuals on surveillance and intelligence tools. The leaked documents show how the war on drugs is also being waged from more discrete fronts. According to the Mexican army, “remote monitoring” has led to the capture of “13 important operators” and “115 generators of violence” of different criminal organizations.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.