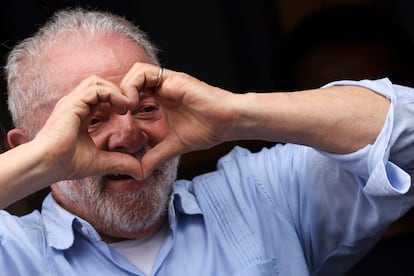

Brazil elections: The return of Lula, the tenacious optimist

At the age of 77, the first working-class president of Brazil – who took millions of people out of poverty and spent 20 months in jail – is on the cusp of winning a third term in power after Sunday’s elections

Few people have traveled so much yet seen so little beyond the walls of hotels and offices as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, 77, who hails from the city of Garanhuns, in the northeast Brazilian state of Pernambuco. Even as the former president of Brazil making a trip to India, he took no time out to see the sights. “In recent years, Lula has done nothing but politics,” says his biographer and friend Fernando Morais, who has been shadowing him for the past 10 years. “He does not take advantage of any trip he’s on to see anything. In India, he didn’t even see the Taj Mahal. He stayed in the hotel receiving politicians.”

Politics is what fuels this pragmatic and chameleon-like individual who, despite his fall from grace, is staging the most unexpected political comeback of recent times. He is seeking a third term at the helm of Latin America’s leading power, which he governed between 2003 and 2010.

The current scenario would have been unthinkable four years ago, when the metalworker turned union leader who founded the Workers’ Party (PT) was all but political history. Jailed six months before the elections for corruption, he could not even vote in the 2018 contest won by far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro, 67, an opponent nostalgic for the military regime that put Lula behind bars during the late 1970s.

The left-wing leader came close to winning the Brazil presidential election in the first round on October 2, in which Congress, governors and regional governments were also decided. He won 48.5% of the vote, five points more than Bolsonaro, who garnered 43.2%, but fell short of the 51% needed to avoid a runoff. As neither candidate passed this threshold, there will be a runoff vote on Sunday, October 30.

After the first round, the election campaign entered a new phase, with the attacks being hurled in an already-bitter electoral battle becoming even dirtier. The volume of disinformation and lies spreading on social media is overwhelming. Lula confessed that he did not fully comprehend the scale of the problem soon enough. “I didn’t imagine the power of lies that spread between telephones,” he said at a recent event to tackle the disinformation and win over Evangelical voters. “I’m analogue, I don’t have a cell phone. I use other people’s phones.”

The two favorites are well known to the electorate. For Lula – which means squid in Portuguese – it is his sixth election, having lost three times before winning twice. After those first three defeats, he was talked out of giving up by Cuba’s Fidel Castro who told him that he could not betray Brazil’s working class.

Lula made history in 2003 when he became the first – and so far only – worker to preside over a country whose income gap beats most. For some, he is the hero who lifted millions out of poverty and gave them opportunities their elders could not have imagined. For others, he is the ringleader of a gang of thieves who looted the public coffers via the Petrobras state-owned oil company – despite the fact that the convictions for which he spent 20 months in jail were overturned. He has always proclaimed his innocence and stated his confidence in the justice system.

For more than 30 years, Lula has been at the center of Brazilian politics. For better or worse, almost everything revolves around him. Few would dispute the fact that he is a skilled negotiator, charismatic, empathetic and astute as well as being a great storyteller. According to his biographer, Fernando Morais, he stood out at school for his oral and written expression despite being a poor student.

The PT is Brazil’s most established party, though it is no longer the powerful electoral machine it was at the height of Lula’s political career. Its territorial power has been waning since the impeachment in 2016 of Dilma Rousseff, Brazil’s first female president. Since the last municipal elections, none of the regional capitals are under its control; only a handful of smaller cities and districts amounting to four million people out of a population of 210 million. The party, at the end of the day, depends on Lula and, despite its 56 seats in Congress, it was only when Lula was released that it managed to present itself as a viable alternative to Bolsonaro.

Lula’s speeches include constant references to his mother, Donha Lindu, an illiterate and austere woman who managed to raise her seven children after leaving an abusive husband. Otherwise known as Eurídice Ferreira de Melo, Lindu is credited with showing Lula how to manage the budget, having had to make ends meet in a poverty-stricken household. Although it was feared Lula would be too radical, he turned out to be quite moderate, though he did implement policies for a slightly fairer distribution of wealth: the average income of Brazilians rose 38% more than inflation under his watch while that of the poorest increased by as much as 84%, according to his Workers’ Party.

For many of the most marginalized in Brazil, Lula is one of their own because he is familiar with poverty. Born in the interior of Pernambuco state, a land ravaged by drought, he was seven when he traveled with his mother and siblings in a van for 13 days to the booming city of São Paulo as part of an exodus of northeasterners to the south in 1952. There, they settled near his father’s second family. His father, Aristides, was a longshoreman who struggled to feed all his offspring while treating them with a cruelty bordering on sadism, as recounted by Morais in his biography, Lula, Volume 1. Life was hard, but there were opportunities. Lula took advantage of them. He worked as a shoeshine and errand boy before entering a vocational school, his springboard to a job as a lathe operator in which he lost a finger; Bolsonaro often calls him “nine fingers.”

Lula likes to listen to an infinite number of opinions before making a decision. He manages ambiguity well and is a politician who moves among poor people, bankers and nobility with ease. His is “a multiple personality,” says Morais, who also flags up Lula’s ability not to hold grudges. Not even his time in prison soured his character. “He has more capacity to make alliances with former enemies than most people I know,” Morais adds. A case in point is his running mate. His vice-presidential candidate is Geraldo Alckmin, a former adversary in the 2006 presidential election, a 70-year-old from the center right, who in the previous election campaign went so far as to say of Lula: “After ruining the country, Lula wants to return to power, to the scene of the crime,” a phrase that Bolsonaro now uses to attack both men.

When Lula entered prison in 2018, he thought he would be behind bars for a matter of days, but the 20 months provided him with enough time to write hundreds of letters to his girlfriend Rosángela Silva, Janja, 55, whom he has just married. It was also enough time to read, which “lent consistency to his principles and objectives,” says Morais, who adds: “He came out much better than he went in.” He was not afraid to ask his lawyers to explain issues such as the history of identity politics, though it should be said that he has trouble digesting certain aspects of modern life, such as the use of cellphones; it irritates him greatly that people look at their phones during meetings.

Much admired abroad, Obama said of him at a G20 summit in 2009: “I love this guy. He is the most popular politician on Earth!” The following year he left office with a popularity rating of 87% as he is fond of pointing out. After touring the world as an ex-president, he ended up mired in the Car Wash corruption scandal. As loved as he became hated, the resentment towards Lula and the PT slightly diminished after his release from prison. Now there is no shortage of Brazilians terrified of Bolsonaro who will vote for him despite being convinced that he has not always been a politician of integrity.

A father of five, Lula has had to deal with other blows such as the death of his first wife together with the baby they were expecting, not to mention the death of his second wife, Marisa, in 2017 and his own fight against throat cancer.

Now Lula enthuses over the warmth of his rallies, the direct contact he has with the people. But there is little in the way of ordinary activities such as going to a restaurant or to the Corinthians stadium, a team he supports.

Before being sentenced in 2018, he still played soccer with friends – which brought him together with Janja – and on the odd Saturday he would organize a churrasco at his house with comrades from his days striking against the military regime. Now even those small personal touches are gone, leaving politics alone. Invariably accompanied by his wife, he has a mission to defeat Bolsonaro, save democracy and return to power to “again include the poor in the budget and ensure all Brazilians have three meals a day.” He himself has said he is aware of the magnitude of the task in an era lacking the wealth once generated by raw materials. “That’s why I work out every day,” he says. To serve Brazil. And to rewrite its history.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.