Brazil elections: Bolsonaro, the strategy of destruction

Before becoming president of Brazil in 2018, the incumbent head of state spent 27 years as a congressman – his rise to power did nothing to temper his violent outbursts, distrustful nature or religious fundamentalism

Perhaps the most influential event in the life of Jair Messias Bolsonaro occurred in 1970. The then-15-year-old lived in the small town of Eldorado with his siblings and parents, a dentist who made a living as a gold miner and a housewife whose pregnancy had been so miserable that she named her son Messias to recognize the miracle of his birth. (His first name, Jair, is after a soccer player.)

At the time, Brazil was a dictatorship. That year, a massive military deployment disrupted the tedious routine in the town, 180 kilometers south of São Paulo. A contingent of soldiers arrived seeking Carlos Lamarca, a deserter who had joined the insurgents and, in his escape, came to fire with the police. The army’s presence impressed the young boy born in 1955 in Glicérico, São Paulo. With time, he reluctantly joined the army, left through a back door and began a long and mediocre career as a congressman. To the surprise of his colleagues, who ignored and scorned him for years, Bolsonaro became president in 2018.

As head of state, the far-right politician – at 67 years old, the father of five children with three wives – has failed to fulfill many of his economic promises. He did, however, promote a stipend for the poor that offers more money and reaches more people than the former program Bolsa Familia. He has removed restrictions on firearm sales and dismantled Brazil’s environmental policy. A favorite of conservative voters, thanks to his firm opposition to abortion and LGBTQ+ rights, and idol of Brazilians who abhor “communism” and gender equality policies, he aspires to win another term in the October 30 runoff elections against 77-year-old ex-president Luiz Inácio Lula de Silva.

For months, Lula has led polls that the president and his supporters consider to be false. It is true that the voter intention polls underestimated his support in the first round. His won a majority in Congress, and was just five points behind Lula, less than half the margin surveys had projected. He won 43.2%, while Lula garnered 48.5%. The polls – the same ones Bolsonaro has constantly questioned – now indicate this margin has narrowed even more, meaning he could win the election. To bolster his support ahead of the vote, his wife Michelle Bolsonaro has been traveling around the country to persuade female voters, particularly conservative women, to vote for her husband.

For months, Bolsonaro and his supporters have also preparing to emulate Donald Trump’s questioning of election results in the United States. It would be the culmination of a strategy of sustained attacks on institutions including the Supreme Court, which has been his primary counterbalance during his time in office. The erosion of Brazilian democracy is clear.

Journalist Carol Pires, author of a fascinating profile on Bolsonaro titled Retrato Narrado (or Narrated Portrait), discovered in her research the significance of that episode in Eldorado a half-century ago. For her, the primary feature of the politician’s personality is that “since his youth he was a paranoid man, given to conspiracies.” His former colleagues “say that they went from allies to enemies in the blink of an eye, with conspiratorial explanations.” He has constantly removed ministers from office. During the pandemic, he changed the health minister four times.

“During his 27 years as a federal congressman, Bolsonaro told the story [of the hunt for the guerrilla member] in different ways,” explains Pires, a reporter and screenwriter. In each version, his own involvement grew. He gained prominence. First, that the raid occurred while he was at school; then, he claimed that he witnessed the shooting; later, he recounted joining the soldiers in the search. Then, the journalist explains, he began introducing conspiracy theories. He would say, without proof, that the guerrilla Lamarca was in the area financed by the mayor of Eldorado, father of Rubens Paiva, a deputy who disappeared under the dictatorship. Decades later, Bolsonaro introduced Dilma Rousseff, who was then a guerrilla, into his account to falsely implicate her in the disappearance of the parliamentarian. Classic Bolsonaro.

In 2016, in the tumultuous session in which the deputies voted on the impeachment of the leftist Rousseff, the far-right politician dedicated his vote to a colonel who tortured her when she was detained. The gesture scared some Brazilians, but for many, it was yet another provocation from congressman Bolsonaro, like the photos of the dictators who ruled between 1964 and 1985 hanging in his congressional office. (They are still there, inherited by a Bolsonarista congress member.)

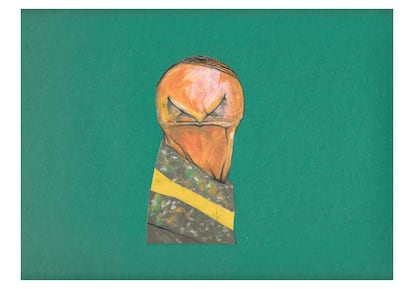

For President Bolsonaro, this election is a duel between good and evil. He appeals to a messianic discourse to explain his arrival at the presidency, a position for which he says that he was appointed by God after surviving the stab wounds of a madman who almost killed him during the previous electoral campaign. The attack was a watershed moment. It shot him to fame and removed him from the electoral debates.

During these four years in power, he has proved wrong those who predicted that he would become more moderate in office. The president Bolsonaro is quite similar to the congressman and candidate Bolsonaro. His absolute lack of empathy with the victims of Covid-19 has cost him dearly. He has made comments such as “my name is Messias but I don’t perform miracles.” He refused to speak about the pandemic deaths, saying, “I’m not an undertaker.” That insensitivity, and the delay in buying the vaccine, with the resulting avoidable loss of life, is one of the reasons most cited by voters who had bet on his promises of change, but will now opt for so-called third way candidates or even for Lula.

The pandemic was a challenge of a caliber that his predecessors did not have to face. But the president’s handling of it is characterized more by his desire to destroy than by his determination to build. “Bolsonaro never had a political project. He was never a congressperson with proposals for public policies,” emphasizes the journalist Pires. “His best-known statements are invariably aggressive against women, homosexuals, Black people, always focused on the annihilation of difference. His logic is that if someone does not agree, that someone is bad and must be destroyed. Who does he want to put in their place? He doesn’t even know it himself,” she says. Bolsonaro’s admirers call all of this “frankness.”

The captain, as he is known in his family, is the patriarch and leader of a political clan. He leads a compact group made up of his three eldest sons, strategically placed in different centers of power: Flávio, the firstborn, known as 01, is a senator; Rio de Janeiro councilman Carlos, 02, is the brain behind social media strategy and congressman Eduardo, 03, the link with the global far right, from Trump to the Spaniards of Vox and the Italian Giorgia Meloni.

For those who knew him – a minority, those who closely follow parliamentary politics – Bolsonaro was an irrelevant congressman, a laughingstock who in three decades had not approved a single law. He was remembered for saying in the 1990s that “the military regime should have finished the job by killing some 30,000″ and telling a leftist congresswoman that she was “too ugly to be raped.”

After Donald Trump’s electoral victory in the United States, Bolsonaro saw his opportunity. He capitalized on the general weariness with corruption, violence and discontent with career politicians (even though he was one of them). And his son Carlos, 02, devised an extremely effective social media campaign.

The patriarch won enough votes to place him 10 points ahead of the Workers’ Party candidate in the second round of elections. He knew how to take advantage of the situation, in addition to forging alliances with evangelicals, police and soldiers. Two out of three Brazilian men and seven out of 10 Protestants voted for him. In the interior of Brazil, he enthused about prioritizing extractivist economic development, disregarding damage to the environment and indigenous communities. That gave him the support of the most thriving economic sector, the agricultural industry, while he pointed to NGOs, native peoples, environmentalists and other sectors as being guilty of hindering economic development that would benefit the locals.

Four years later, if the poll forecasts come true, he will be the first Brazilian president this century to not be reelected.

It is impossible to understand Bolsonaro without keeping in mind that he was trained in the military academy during the prime years of the dictatorship. He left the institution in 1988, just when Brazil was returning to the path of democracy. Bolsonaro was invited to return to civilian life after telling Veja magazine about his plans to plant a bomb to protest the low pay of soldiers. The author of the profile of Bolsonaro maintains that he “brings that military coup mentality to politics.” Her conclusion, after many months immersed in the nooks and crannies of the president’s life, is that he “was a bad soldier, a bad congressman and a bad president.”

The far-right politician and his followers insist that the polls again underestimate him, just as in 2018. They maintain that the media and the electoral authorities are in cahoots to throw him out and ensure Lula’s win. The proof, they say, is in the crowds he gathers at his events – traditional families, motorcycle and gun enthusiasts. It is not known what will happen if the electoral authorities declare his opponent’s victory.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.