Is Putin losing the war? The balance of the first phase of the conflict in Ukraine

The Russian invasion has lost its impetus and a series of setbacks has forced the Kremlin to reorganize its forces, raising questions about its military power

On February 24, Russia attacked Ukraine in the biggest military offensive witnessed on the European continent since the end of World War II. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s stated goals at the time were to prevent Ukraine from joining NATO, to demilitarize and to “de-Nazify” the neighboring country. It was the start of a war operation that is upturning the world order. A little over a month later, the Kremlin feels that the goals set out for phase one are being fulfilled “successfully.” A new phase is allegedly about to begin, focusing on “liberating” the Donbas region in southeastern Ukraine. But the facts, which include a series of setbacks leading to a significant withdrawal and reorganization of Russian troops, do not support this version of events. What is the balance of war so far?

Russia has been unable to capture Ukraine’s main cities – the capital Kyiv, Kharkiv, Mykolaiv and even the badly battered Mariupol are still holding out. Odessa remains free, and Ukrainian forces are regaining ground in several parts of the country. Russian troops are withdrawing from their positions on the northern front, and most particularly from their positions around Kyiv. Analysts with the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) believe that Russian forces have abandoned their efforts to capture Kharkiv, the second-largest city in Ukraine and the target of an intense offensive since the beginning of the invasion. Russian forces are still shelling the city, but seem to have given up on their attempts to encircle and control it.

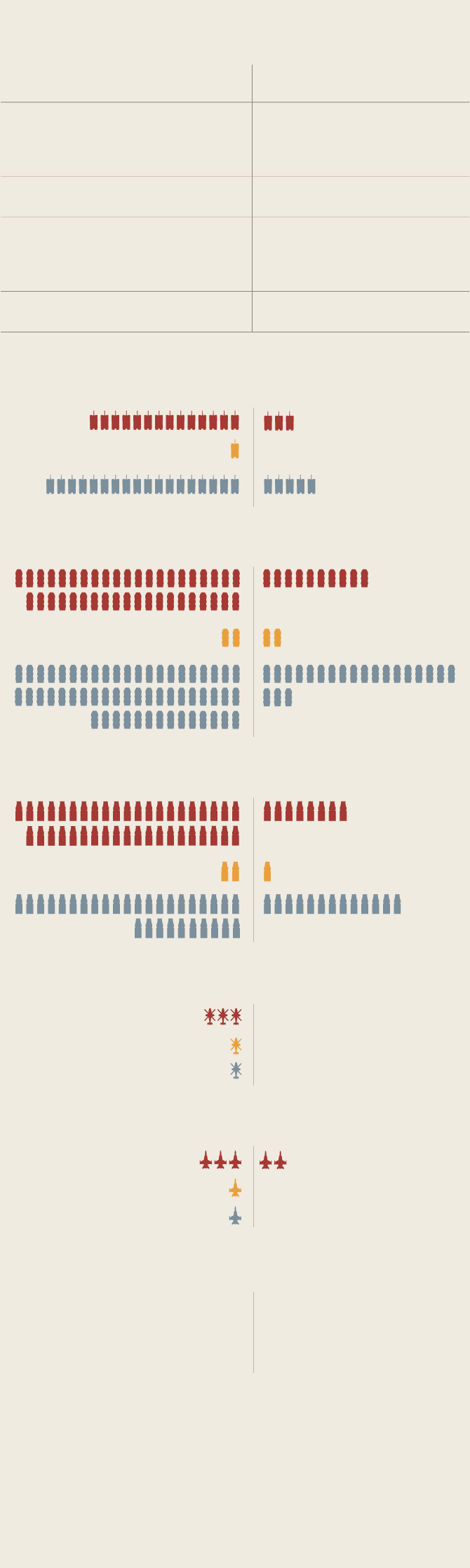

Balance

Russian military victims

Dead

Injured

According to

Moscow

1,351

3,825

Kyiv

17,000

Pentagon

10-15% of forces

UN

7,000-15,000

dead

Figures provided by Kyiv (March 29);

Moscow and the Pentagon (March 25);

UN (March 24)

Ukrainian military victims

Dead

Injured

According to

Moscow

14,000

16,000

Kyiv

1,300

Civilians

1,179 dead and 1,860 injured

(according to the UN)

4 million refugees

6.5 million displaced people

*The human and military losses during a war are usually estimates due to the difficulty of verifying the figures on the ground

Balance

Russian military victims

Ukrainian military victims

Dead

Injured

Dead

Injured

According to

According to

Moscow

Moscow

1,351

3,825

14,000

16,000

Kyiv

Kyiv

17,000

1,300

Pentagon

10-15% of forces

Civilians

UN

7,000-15,000

dead

1,179 dead and 1,860 injured

(according to the UN)

Figures provided by Kyiv (March 29);

Moscow and the Pentagon (March 25);

UN (March 24)

4 million refugees

6.5 million displaced people

*The human and military losses during a war are usually estimates due to the difficulty of verifying the figures on the ground

The realization of failure on several lines of attack and the attrition of its forces is forcing the Kremlin to reorganize its deployment in Ukraine. There have been tremendous material losses.

Military losses

Russia

Ukraine*

Units

destroyed

1,010

212

Damaged

40

22

Captured or

abandoned

1,063

397

2,113

631

Total

Tanks

26

139

6

44

180

Armed vehicles

91

410

12

12

221

569

Other vehicles

74

402

8

16

121

306

Helicopters

1

30

3

2

Aircraft

18

28

1

2

6

Ships

1

2

2

11

*The specialized website Oryx, which is documenting loss of military equipment by Russia and Ukraine based on visual evidence, is offering a count that helps gain insight into the material cost of this conflict. Ukrainian losses are probably undercounted.

Military losses

Russia

Ukraine*

Units

destroyed

1,010

212

Damaged

40

22

Captured or

abandoned

1,063

397

2,113

631

Total

Tanks

26

139

6

180

44

Armed vehicles

91

410

12

12

221

569

Other vehicles

74

402

8

16

121

306

Helicopters

1

30

3

2

Aircraft

18

28

1

2

6

*The specialized website Oryx, which is documenting loss of military equipment by Russia and Ukraine based on visual evidence, is offering a count that helps gain insight into the material cost of this conflict. Ukrainian losses are probably undercounted.

Ships

1

2

2

11

“The first phase has been a Russian military failure of colossal proportions, a truly impressive thing. It will be the subject of study at military academies due to the accumulation of mistakes,” says François Heisbourg, a special advisor for France’s Foundation for Strategic Research (FFRS), the leading French center of expertise on international security and defense issues. The core cause, says Heisbourg, is an erroneous political analysis by the Kremlin that led officials to believe there would not be such a strong resistance by Ukrainians, a fact that also led to inadequate military planning.

“It’s been a disaster,” agrees Ruth Deyermond, a scholar at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London who specializes in security in the post-Soviet space. “We are observing great losses, communication and logistical failures, signs of corruption. They are being forced to resort to mercenaries, and they are withdrawing from Kyiv. No doubt Russia is losing the war. We cannot confidently say that Ukraine is winning, but we can clearly say that Russia is losing,” she says.

The following is an analysis of the combination of strategic and tactical factors that have led the warring sides to the point where they are at, in a war with an as yet uncertain outcome that will define an era. “The initial failure is not an indication of what will happen later,” warns Heisbourg. The conflict could be long and something could tip the balance of war again.

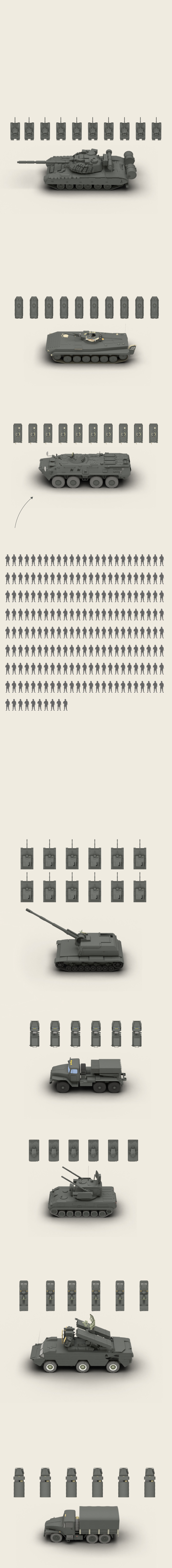

Land invasion

A shock force of between 150,000 and 190,000 Russian troops invaded Ukraine, organized into so-called BTG (Battalion Tactical Groups), the key operating unit of the Russian army. These are formations equipped with about 50 armored vehicles, designed to act with a high degree of autonomy and with great firepower. The United States estimates that Russia has deployed around 100 BTGs in Ukraine, which according to the Pentagon represents 75% of the total number of units at the Kremlin’s disposal.

Each BTG is modular and includes several companies with armored vehicles and artillery batteries. This is the most common structure:

Tanks

1 company of 10 tanks

T-80, T-72, T-90 or T-64

Not to scale

Troop transport

1 company of 10 caterpillar-tread vehicles

BMP-1, BMP-2 or BMP-3

1 or 2 companies of 10 troop

transport vehicles

BTR-60, BTR-70 or BTR-80

Each BMP and BTR vehicle

carries seven soldiers

Approximately

210 soldiers

Taken together, a Battalion Tactical Group can have around 1,000 troops

Artillery

2 or 3 batteries of 6 Mobile Howitzer

self-propelled artillery systems

Msta-SM2

1 battery of 6 rocket launchers

MLRS B M-21, BM-27, B17 or TOS-1A

1 or 2 anti-aircraft batteries

2K22M1 Tunguska

Or a mobile battery of surface-to-air

missile system

9K33 Osa

Support and logistics

Support vehicles such as trucks to transport

troops, engineering equipment, radar,

control systems, mortars, etc.

BREM-1

Each BTG is modular and includes several companies with armored vehicles and artillery batteries. This is the most common structure:

Tanks

1 company of 10 tanks

Not to scale

T-80, T-72, T-90 or T-64

Troop transport

1 company of 10 caterpillar-tread vehicles

BMP-1, BMP-2 or BMP-3

1 or 2 companies of 10 troop transport vehicles

BTR-60, BTR-70 or BTR-80

Each BMP and BTR vehicle carries seven soldiers

Approximately

210 soldiers

Taken together, a Battalion Tactical Group can have around 1,000 troops

Artillery

2 or 3 batteries of 6 Mobile Howitzer self-propelled artillery systems

Msta-SM2

1 battery of 6 rocket launchers

MLRS B M-21, BM-27, B17 or TOS-1A

1 or 2 anti-aircraft batteries

2K22M1 Tunguska

Or a mobile battery of surface-to-air missile system

9K33 Osa

Support and logistics

Support vehicles such as trucks to transport troops, engineering

equipment, radar, control systems, mortars, etc.

BREM-1

Tanks

1 company

of 10 tanks

Each BTG is modular and includes several companies with armored vehicles and artillery batteries. This is the most common structure:

Not to scale

T-80, T-72, T-90 or T-64

Troop transport

1 company of 10 caterpillar-tread vehicles

1 or 2 companies of 10 troop transport vehicles

BMP-1, BMP-2 or BMP-3

BTR-60, BTR-70 or BTR-80

Each vehicle carries seven soldiers

Approximately

210 soldiers

Taken together, a Battalion Tactical Group can have around 1,000 troops

Artillery

2 or 3 batteries of 6 Mobile Howitzer self-propelled

artillery systems

1 battery of 6 rocket launchers

MLRS B M-21, BM-27, B17 or TOS-1A

Msta-SM2

1 or 2 anti-aircraft batteries

Or a mobile battery of surface-to-air missile system

2K22M1 Tunguska

9K33 Osa

Support and logistics

Support vehicles such as trucks to transport troops, engineering

equipment, radar, control systems, mortars, etc.

BREM-1

But these powerful units have been slowed down by numerous problems, including their own mistakes and the successes of the Ukrainian defense.

In tactical terms, Russia’s decision to advance by road straight towards its main urban targets made troop movements highly predictable and exposed them to ambush. Failures in equipment maintenance and logistics, and an often inadequate infantry protection of the flanks, aggravated their weakness.

In operational terms, the Pentagon has also observed failures in the chain of communication, with a growing reliance on unsafe lines. “The use of unencrypted lines has allowed Ukrainian forces to locate and kill several Russian generals,” says Deyermond.

Overall, command and control have shown signs of ineffectiveness in dealing with an operation of a scale not experienced in decades by Russian forces. And a hierarchical structure that rarely delegates to middle management has reduced agility.

The scope of Russian targets has led to troop dispersal on the ground. However, this has not prevented them from achieving clear supremacy on the fronts.

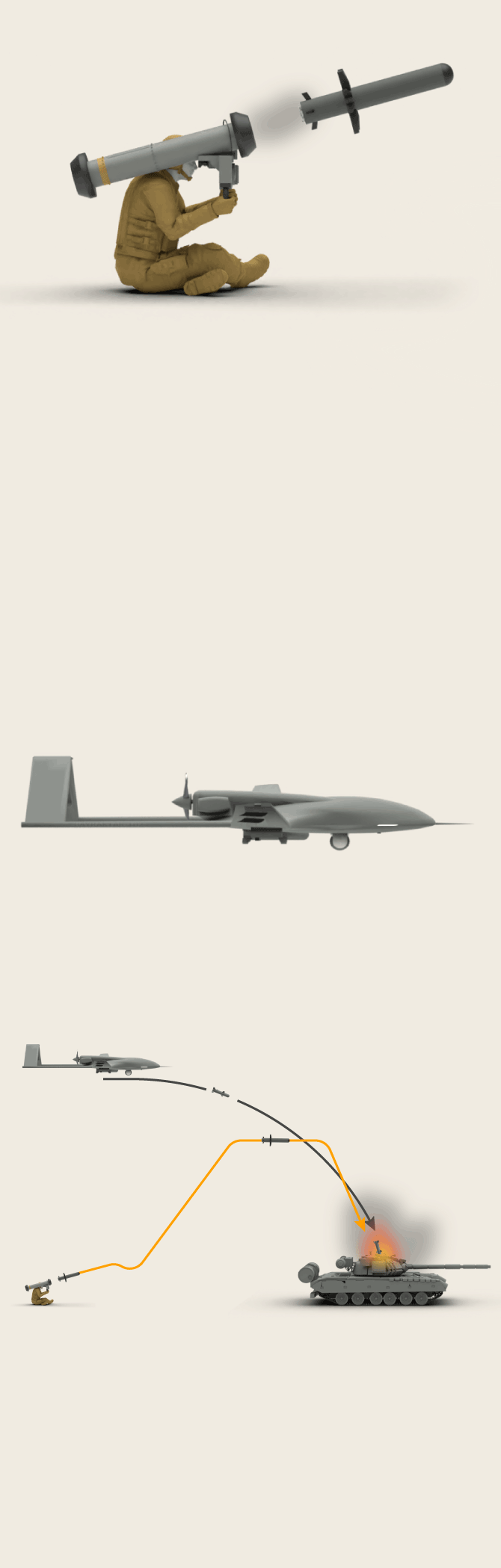

Ukrainian forces have made the most of this situation, striking the Russian columns repeatedly with anti-tank weapons such as Javelins, or from the sky with drones.

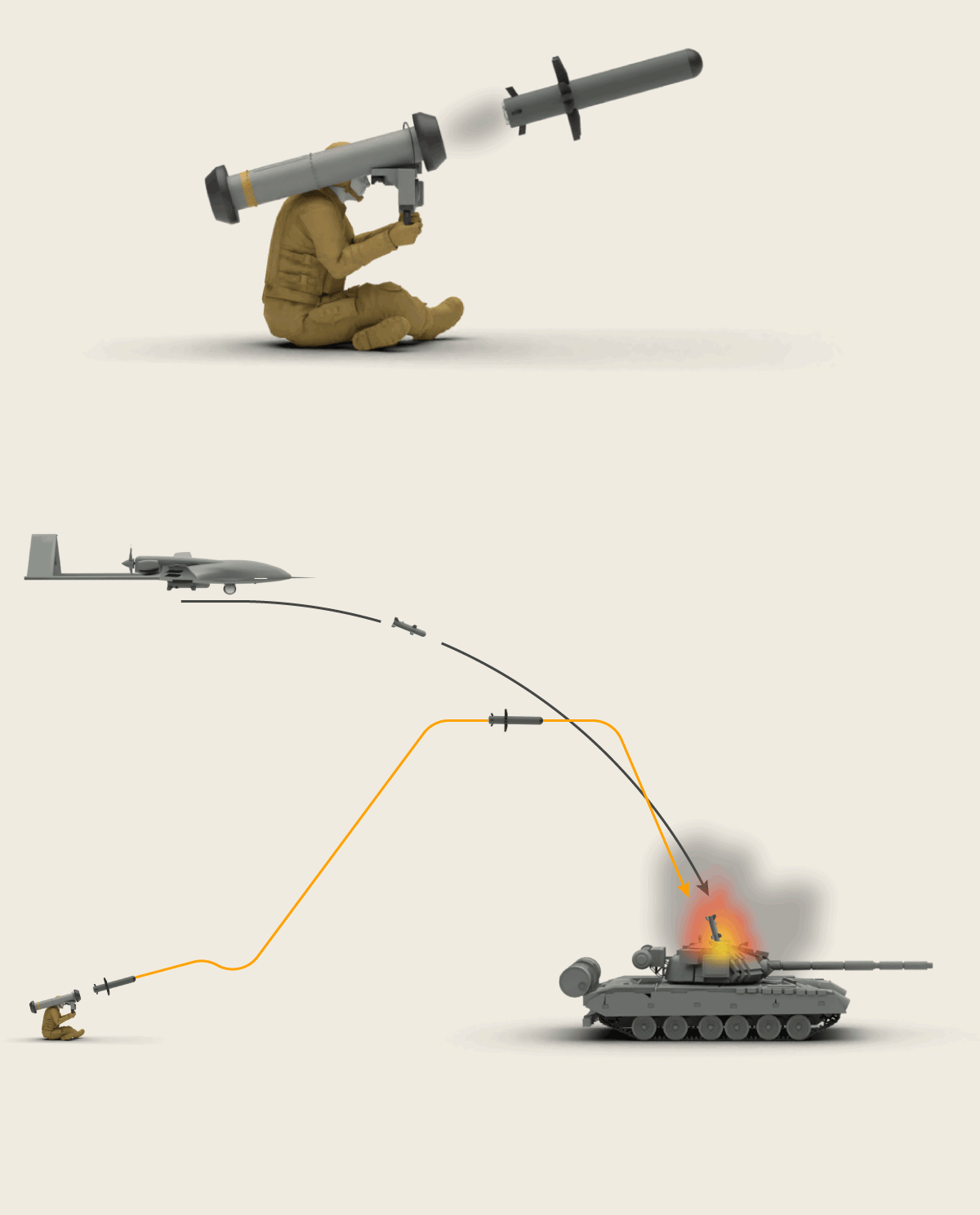

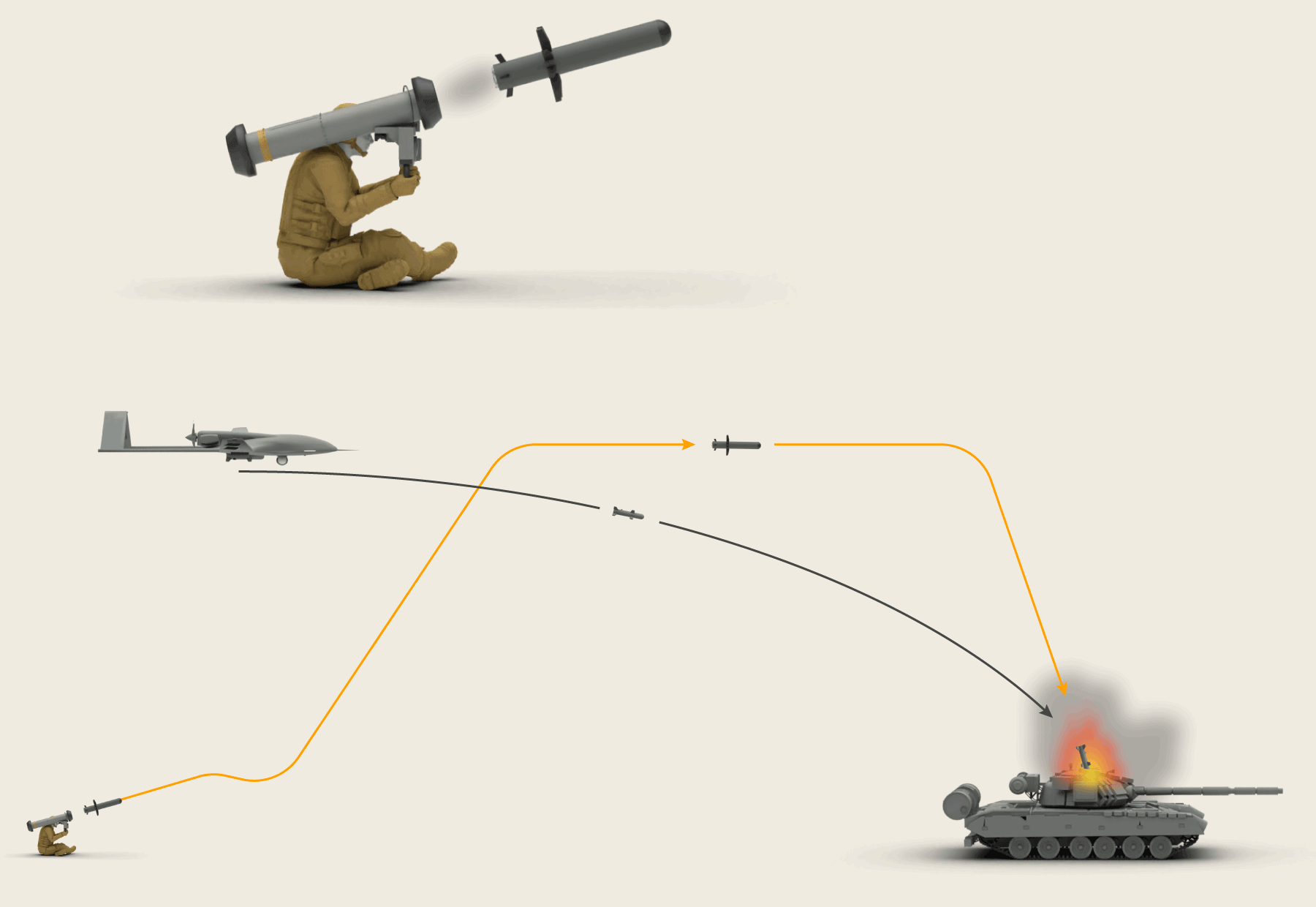

Portable anti-tank missile

system, FGM-148 Javelin (US)

Projectile

(15.9 kg)

Ukrainian soldier

Ukraine has received training and military material such as anti-tank missiles and the Bayraktar TB2 combat drone. The Javelin anti-missile system, which is easy to use and has great destructive power, has helped Ukraine stop Russia’s armored convoys.

6.5 meters

Turkish combat drone

Bayraktar

Javelin

Russian tank T-80

The Javelin missile can reach targets 2.5 miles (4 km) away. The projectile takes a vertical trajectory that increases its effectiveness against armored vehicles.

Portable anti-tank missile

system, FGM-148 Javelin (US)

Projectile

(15.9 kg)

Ukraine has received training and military material such as anti-tank missiles and the Bayraktar TB2 combat drone. The Javelin anti-missile system, which is easy to use and has great destructive power, has helped Ukraine stop Russia’s armored convoys.

Ukrainian soldier

6.5 meters

Turkish combat drone

Bayraktar

Javelin

Russian tank T-80

The Javelin missile can reach targets 2.5 miles (4 km) away. The projectile takes a vertical trajectory that increases its effectiveness against armored vehicles.

Portable anti-tank missile

system, FGM-148 Javelin (US)

Ukraine has received training and military material such as anti-tank missiles and the Bayraktar TB2 combat drone. The Javelin anti-missile system, which is easy to use and has great destructive power, has helped Ukraine stop Russia’s armored convoys.

Projectile

(15.9 kg)

Ukrainian soldier

6.5 meters

Turkish combat drone

Bayraktar

The Javelin missile can reach targets 2.5 miles (4 km) away. The projectile takes a vertical trajectory that increases its effectiveness against armored vehicles.

Russian tank

T-80

Javelin

Heisbourg underscores three key factors behind Ukraine’s achievements: “A brave combat spirit, weapons delivered by the West, and training by Western countries that has given Ukraine a better organizational ability than the Russians, who are very uncoordinated.”

The desire to defend one’s country and fellow citizens is a motivational element that is hard to beat. And President Zelenskiy has been an inspirational leader.

Weapons supplied by the West, even if they lack sophisticated systems, are proving to be of great use for the type of combat that is taking place in Ukraine.

Besides that, Ukrainian forces are no doubt benefiting from important intelligence and advisory support from the West. Espionage, satellite observation technology and cyberdefense support from Western public agencies and private companies – including Microsoft and Starlink – are all proving to be important factors.

The absence of a large-scale cyberattack has surprised many. “That’s not to say that we haven’t seen cyber in this conflict. We have – and lots of it. We’ve seen sustained intent from Russia to disrupt Ukrainian government and military systems‚” said Sir Jeremy Fleming, Director of Britain’s General Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), in recent statements. But there have been no significant effects.

Ukraine has also benefited from Russia’s inability to achieve air supremacy, a fact that has puzzled many experts. This is fundamentally due to Russia’s failure to strike Ukrainian anti-aircraft defenses, largely because of imprecise information about their location or during strikes. Russia has launched many attacks and caused a lot of destruction, but it has failed to decisively degrade Ukraine’s military abilities.

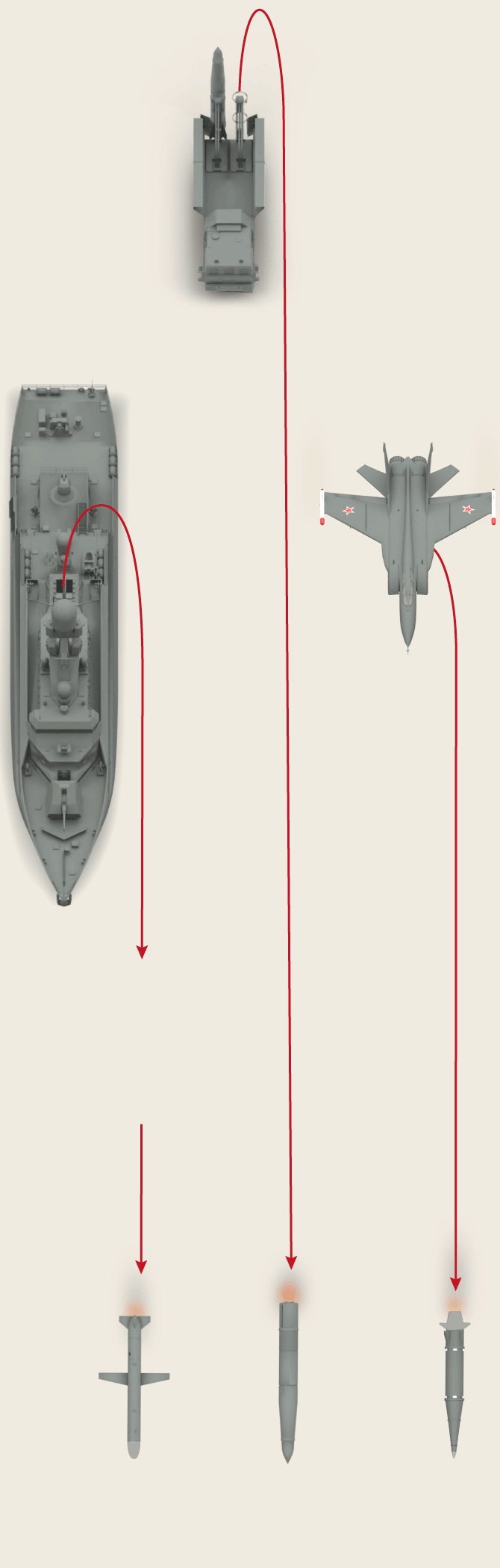

Missile offensive

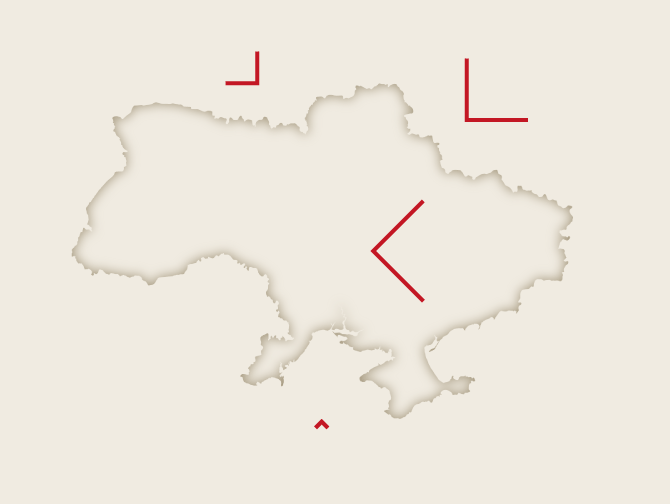

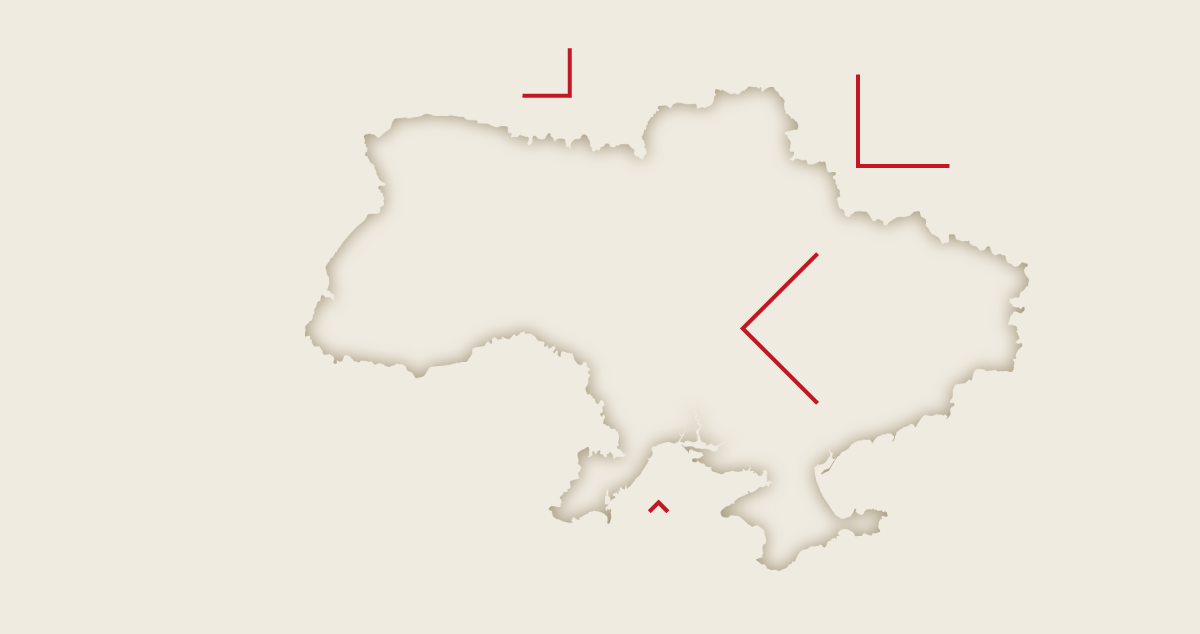

From the beginning, Russia has sought to make the most of its ample missile potential. According to a Pentagon tally, by March 31 the country had launched over 1,400 cruise and ballistic missiles.

80 from

Belarus

300 from

Russia

400 from

Ukraine

Where the first 800 missiles that hit Ukraine were launched from:

6 from the

Black Sea

80 from

Belarus

300 from

Russia

Where the first 800 missiles that hit Ukraine were launched from:

400 from

Ukraine

6 from the

Black Sea

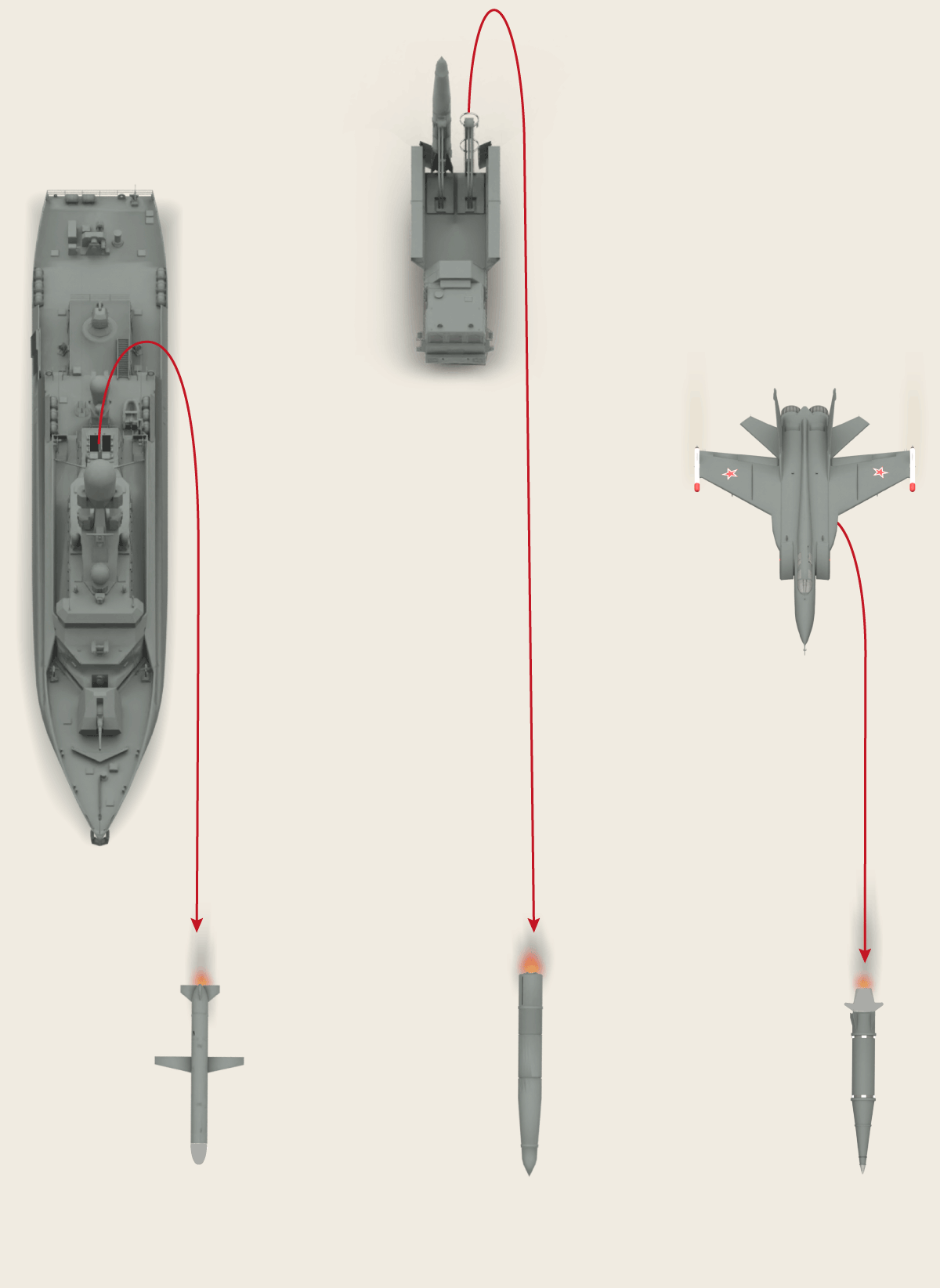

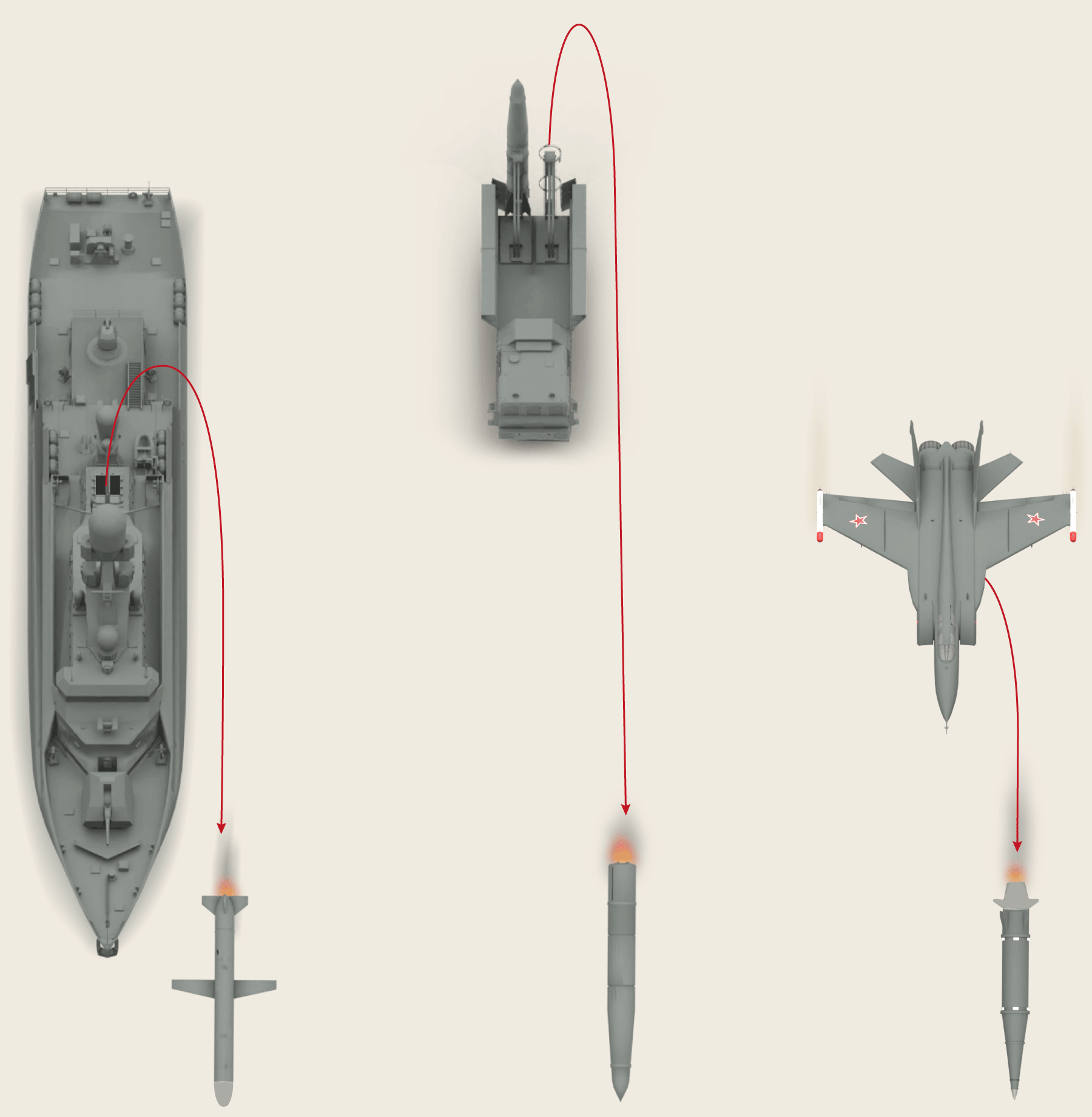

Launch systems

Russia has a large arsenal of missiles thanks to decades of defense industry development, first under the Soviet Union and later under President Vladimir Putin’s renewed drive. The star of the arsenal is very likely the Iskander-M, which can shoot short-range ballistic missiles. The army has also used Kalibr cruise missiles, and Moscow claims to have deployed a Kinzhal hypersonic missile.

Iskander missile launch vehicle

Russian corvette deployed in the Black Sea with Kalibr cruise missiles

Kinzhal hypersonic missiles can be launched from MiG aircraft or the Tupolev Tu-22M bomber

Russia has used these missiles to bomb cities from afar.

Reach:

up to

373 miles

(600 km)

Reach:

up to

311 miles

(500 km)

Reach:

up to

1,864 miles

(3,000 km)

Kalibr

missile

Iskander

missile

Kinzhal

hypersonic

missile

The models are

not to scale

Russia has used these missiles to bomb cities from afar.

Iskander missile launch vehicle

Kinzhal hypersonic missiles can be launched from MiG aircraft or the Tupolev Tu-22M bomber

Russian corvette deployed in the Black Sea with Kalibr cruise missiles

Reach:

up to 373 miles

(600 km)

Reach:

up to

311 miles

(500 km)

Reach:

up to

1,864 miles

(3,000 km)

7 meters

7 meters

Iskander

missile

Kinzhal

hypersonic

missile

Kalibr

missile

Russia has used these missiles to bomb cities from afar.

The models are

not to scale

Iskander missile launch vehicle

Russian corvette deployed in the Black Sea with Kalibr cruise missiles

Kinzhal hypersonic missiles can be launched from MiG aircraft or the Tupolev Tu-22M bomber

Reach:

up to 373 miles

(600 km)

Reach:

up to 311 miles

(500 km)

Reach:

up to 1,864 miles

(3,000 km)

7 meters

7 meters

Kinzhal

hypersonic

missile

Kalibr

missile

Iskander

missile

Defending against missile attacks is extremely difficult, and even the world’s most advanced armed forces have limited intercept capabilities. Ukraine has a S-300 anti-missile system designed in Soviet times and developed at a later date.

At first, Russia picked targets that were clearly military in nature, with the goal of undermining its opponent’s operational capabilities. But progressively it has been including civilian targets as well, ranging from broadcasting towers to shopping malls and even hospitals.

The Pentagon believes that Russia is still sitting on a large stash of ballistic and cruise missiles, but that it might be running short of precision-guided missiles, forcing it to use increasingly inaccurate weapons as the conflict drags on.

Russia’s remarkable missile capacity has caused a lot of damage but has failed to undermine Ukrainian resistance, both in terms of military capability and popular resolve.

Air combat

Russia’s inability to neutralize Ukraine’s anti-aircraft defense is conditioning the operability of Russian aviation, which cannot move as it wishes within Ukrainian airspace. This represents a limitation on Russian air raids to protect their advancing ground forces or to strike targets. The Pentagon has estimated that Russia is using 60% of its air force in Ukraine.

Washington believes that Russian aircraft have been going out on approximately 250 to 340 missions a day, but that many of these have not penetrated into Ukrainian territory or only in a limited manner. Ukrainian aircraft, for their part, are flying five to 10 missions a day.

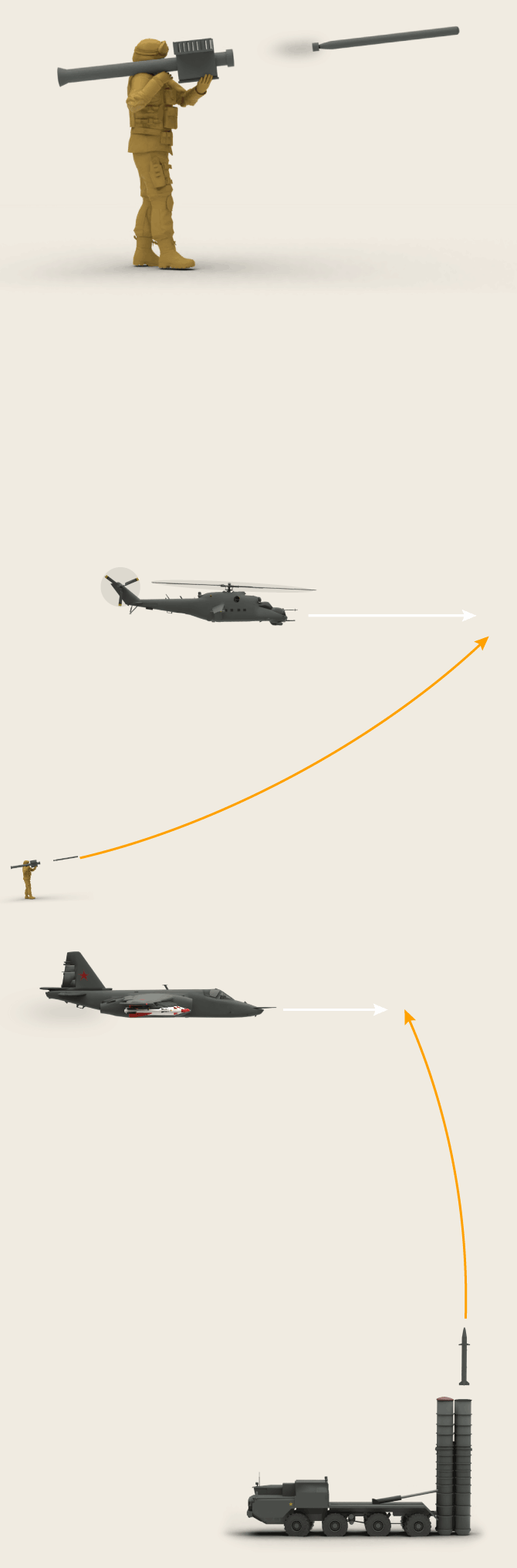

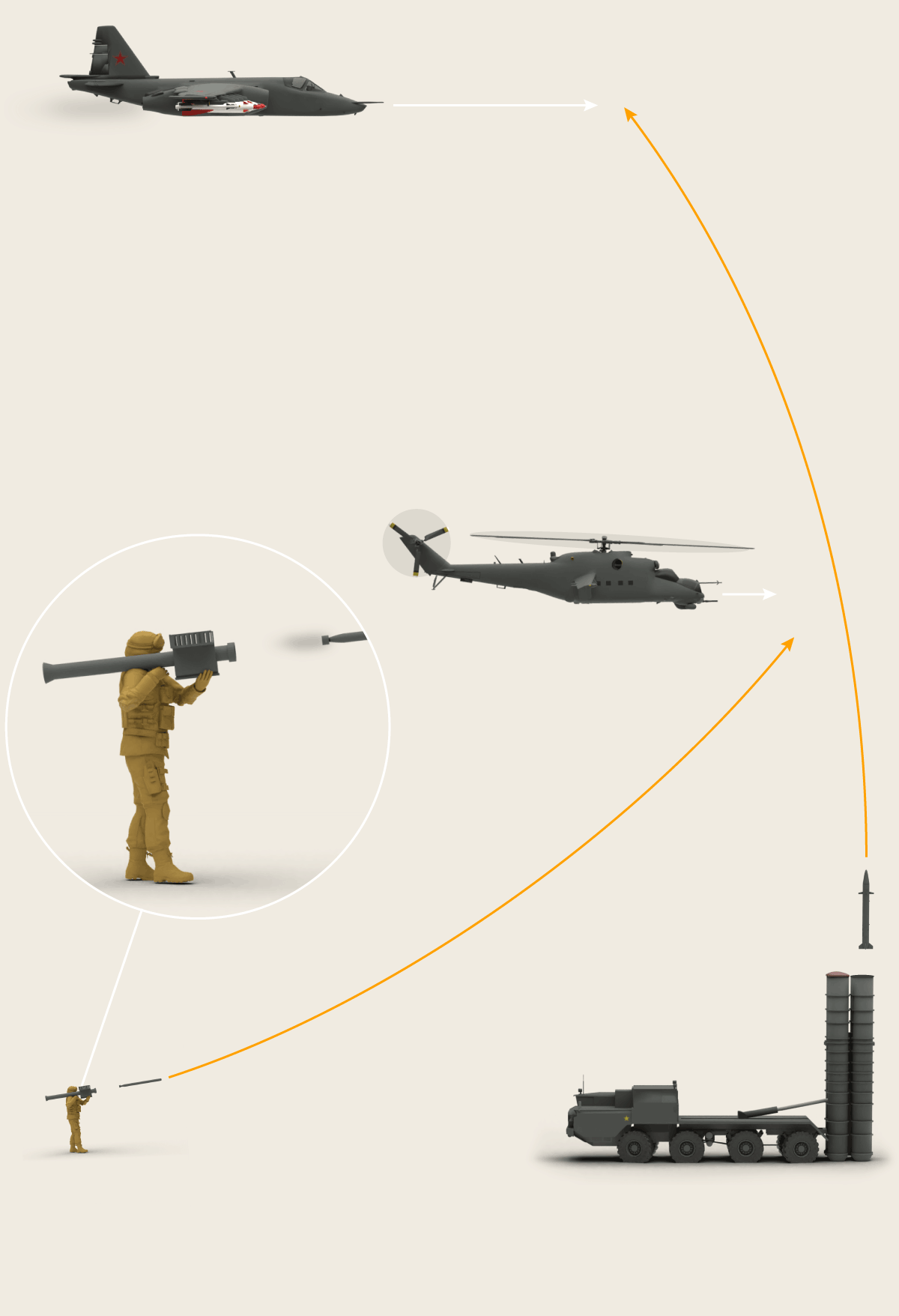

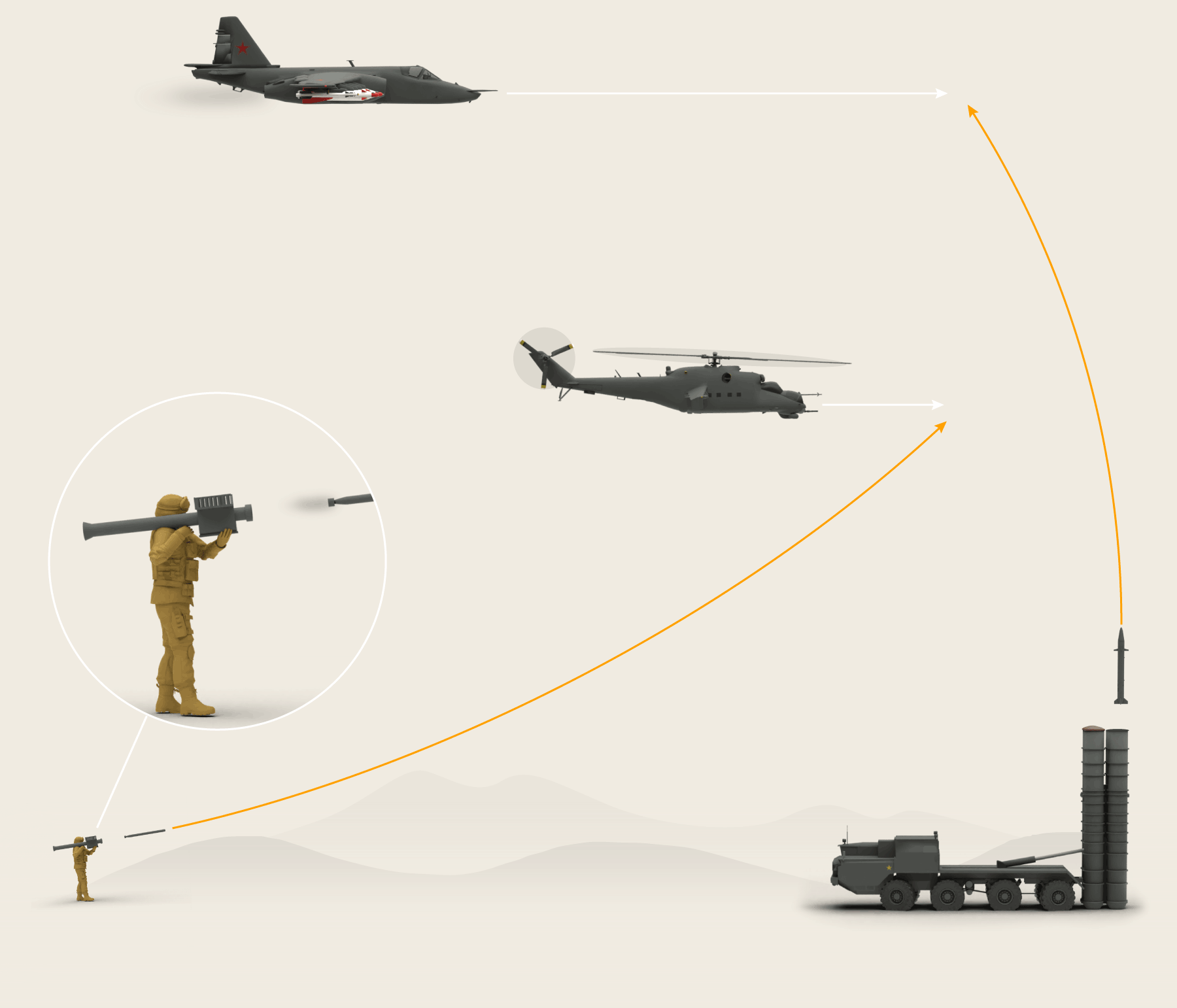

Besides the S-300, which are quite efficient against airplanes, Ukrainian forces are being supplied with significant amounts of portable Stinger missiles, which are dangerous for low-flying aircraft.

Stinger

surface-to-air

missiles (US)

The US and other countries continue to send weapons to Ukraine, such as Stinger missiles which Ukrainian soldiers can use to shoot down helicopters.

Russian M1-35

helicopter

Russian fighter bomber

Sukhoi Su-25

With the S-300 anti-missile system, Ukrainian troops try to intercept Russian fighter bombers.

Ukrainian anti-missile

system S-300 (origin: Russia)

Russian fighter bomber

Sukhoi Su-25

The US and other countries continue to send weapons to Ukraine, such as Stinger missiles which Ukrainian soldiers can use to shoot down helicopters.

Russian M1-35

helicopter

Stinger

surface-to-air

missiles (US)

Ukrainian anti-missile

system S-300 (origin: Russia)

Ukranian

soldier

With the S-300 anti-missile system, Ukrainian troops try to intercept Russian fighter bombers.

Russian fighter bomber

Sukhoi Su-25

The US and other countries continue to send weapons to Ukraine, such as Stinger missiles which Ukrainian soldiers can use to shoot down helicopters.

Russian M1-35

helicopter

Stinger

surface-to-air

missiles (US)

With the S-300 anti-missile system, Ukrainian troops try to intercept Russian fighter bombers.

Ukranian

soldier

Ukrainian anti-missile

system S-300 (origin: Russia)

Urban warfare

Russia has been unable to capture Ukraine’s major cities, which would have effectively subjugated the country. Wresting control of the cities from an adversary as determined as the Ukrainian defense involves launching ground attacks, which are among the most dangerous kind of action for any army.

Military experts note that urban combat gives the advantage to the defender, who has many opportunities for hiding.

The attacker could also choose to bomb the city intensely. If he is prepared to accept the ignominy of completely gutting the target, this would certainly clear the way forward. If, instead, he manages to encircle the city completely, it could prevent delivery of essential supplies. But until either of those situations comes to pass, if ever, the defense is keeping up the fight and any Russian incursion will mean exposing the latter’s soldiers to attacks.

Conclusion

Conflicts are dynamic. Like Heisbourg notes, the circumstances that have defined the first month and a half of conflict are not necessarily an indication of how things will turn out in the end. Besides that, available information is neither comprehensive nor transparent.

Available data suggests that Russia is inflicting tremendous damage on Ukraine. It has made huge inroads into Ukrainian territory and its potential for dragging out the war is significant. What’s more, it has managed to get the government in Kyiv to openly talk about negotiating a neutral status for Ukraine as part of a potential peace deal.

But Russia has also sustained tremendous losses in a little over a month. The fact that authorities have admitted to 5,000 casualties, including the dead and the injured, is already remarkable in itself, but it means that the reality is probably a lot worse than Moscow is admitting. Material losses have been huge as well. Rebuilding these forces, notes Heisbourg, will prove extremely tricky given the sanctions that Russia’s defense industry has been hit with and the strong dependence of several sectors. This reality will define Russia’s military future beyond the effects of the Ukraine war.

This operation is showing the world the limitations of Russian forces, which were believed to be modernized and world-class level. “But that is not the case,” adds Deyermond.

On the economic front, Russia continues to earn money from its hydrocarbon exports. Following an initial and sudden collapse, the ruble is gaining lost ground. But the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) recently forecast that Russia’s GDP will contract 10% in 2022, while the inflation rate remains above 15%. The brain drain is also cause for concern in Moscow. It is a complex situation for a country trying to keep up the war effort.

Nobody beyond Putin’s closest circle knows what the Kremlin’s original plans and expectations might have been. Judging by public statements, it would appear that the goal of “demilitarizing” Ukraine is nowhere in sight. As for its “de-Nazification,” this is an ambiguous concept, but the general logic of Russia’s rhetoric would indicate that it essentially means a regime change in Kyiv. This does not appear to be imminent, either.

What Ukrainian President Zelenskiy has accepted is to discuss his country’s neutrality and drop his ambition to join NATO. But he is only willing to do so in exchange for guarantees that resemble those included in Article 5 of the NATO Treaty. “In any case, NATO membership was never really in the cards, so achieving this in exchange for so many losses could hardly be considered a positive result for Moscow.” For now, Kyiv is not capitulating to Moscow’s territorial claims, although it is willing to temporarily put the contentious issue of Crimea on hold.

Whatever the actual goals and expectation of the Kremlin, its use of the term “success” to describe the situation has little basis in facts. The elements on view at the moment do not paint a picture of Russian victory.

Russian forces appear to be reorganizing in order to focus their efforts on the eastern Donbas region. This might grant them improved attack capabilities. They will likely attempt to encircle Ukrainian forces in the area, squeezing them between Russian positions in the north and the south. But Deyermond stresses that the initial phase of the operation has led to significant attrition: Russian troop morale is low, and so is the ability to bring in fresh equipment and forces. Ukraine’s spirits, on the other hand, remain high.

Time will tell whether this initial phase of the war is just the beginning of a new case of military defeat by an invading power with superior strength, just like the USSR and the US experienced in Afghanistan.

Credits: Video was selected, verified and edited by

Sources and methodology: The source for military developments on Ukrainian territory was the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War. The map of urban density is based on data provided by worldpop.org while physical maps are based on naturalearthdata.com. The Pentagon is the source of information about the first 800 missiles deployed by Russia, and Globalsecurity.org for the characteristics of Russian BTGs. Information on equipment losses by both sides comes from the specialized website Oryx, whose lists are based on documentary evidence. The segment on urban warfare is based on John Spencer’s The Mini-Manual for the Urban Defender. Information about missiles was taken from the Missile Threat project of the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies.