From Anne Frank’s diary to TikTok: the Ukraine war (almost) live

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is the first armed conflict to be broadcast on TikTok. Memories of war, which used to be recorded in secret, are now being uploaded in real time

Just as Vietnam was the first televised war, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has become the first conflict to be broadcast via TikTok. As noted by journalist Kyle Chayka in The New Yorker, in times of war social networks can sometimes be “the source that we trust the most.” Many of those documenting the war are journalists, while many others have no media affiliation, but they all possess a crucial weapon: a smartphone.

In the voyeuristic and social media-obsessed world we live in, it is little surprise that there are people who document their daily existence online, even from a city besieged by war. Documenting reality, although it has often been considered a purely egotistical act, is at the end of the day a way of connecting with other human beings, to share experiences and inform. Several memoirs written by people persecuted during the Holocaust have entered the pantheon of literary history. Some of them survived and were able to utilize their experiences as a vital driving tool, like the Austrian psychoanalyst Viktor E. Frankl; others, such as the Hungarian Nobel laureate Imre Kertész and the Italian Primo Levi, remained inextricably tied to the suffering it had caused them. Others were killed in the extermination camps, such as Anne Frank, who wrote the final entry in her diary – which would not see the light of day until three years later – when she was just 15 years old.

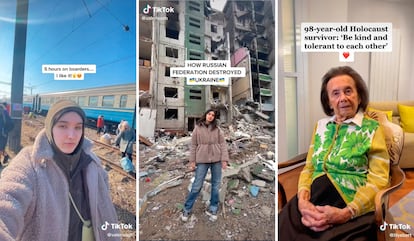

Times have changed. Today, autobiographies can be digitally reconstructed from social networks, instead of read in printed book form. Marta Figlerowicz, associate professor of Comparative Literature and English at Yale University, highlights the speed with which they can be put together. “Many people may think that is the reason TikTok narratives are superficial, but it doesn’t have to be this way. Creators should explore short rhetorical forms,” she says. One such example is Lily Ebert, a 98-year-old Holocaust survivor who has used TikTok to share her experiences of Auschwitz with her almost two million followers. Or the Ukrainian Valeria Shashenok, a 20-year-old with a passing resemblance to the celebrity American Tiktoker Charli D’Amelio, who went viral on the platform narrating her day-to-day existence in a bunker in Chernihiv, where she and her family were sheltering from Russian bombardments.

What makes Shashenok stand out from other people documenting their experience in the middle of a war is her ironic tone. “I’m living my best life, thanks Russia!” she wrote in one post, accompanied by a smiling face emoji, which garnered 42 million views. “And of course, thanks Putin!” she wrote in another, her thumbs aloft as she explained her family had been left without electricity. When she is able to leave the bunker, she documents the destruction. “Going out on the street and seeing what Putin has done to my city,” while a cheerful tune plays over the footage. While her mother makes borscht soup, she says she is “adding Putin’s blood to the beetroot.” Her use of humor only serves to heighten the tension of her situation, as when she refers to herself in the third person: “She cooks pasta in a bunker and dreams she is in Italy.”

Autobiographies built on social media have a crucial advantage over traditional autobiographies. One of TikTok’s principal advantages is that it provides affective needs, as revealed by a 2020 study carried out among adolescents and pre-adolescents in Denmark by Christina Bucknell Bossen and Rita Kottasz, which found the platform met 74.7% of those needs in that age group. Comments and “likes” on posts bring immediate gratification that, in this case, can help to alleviate the trauma of war.

“One of the conclusions we have come to while researching the representation of self in digital environments is that despite being offered the opportunity to conceal ourselves under anonymity, what we actually do is to express out identity in a more fluid way while adapting to the context. We use autobiography as a virtual socialization strategy,” says Professor Carlos Arcila of the Department of Sociology and Communication at the University of Salamanca.

Shashenok’s 858,000 TikTok followers are engaged in a debate between what some consider the trivialization of war and delirious opportunism, and those who have voiced their admiration for the transformative ability to find humor in tragedy, in a kind of nod towards Roberto Benigni in Life Is Beautiful. Other attribute Shashenok’s output to the creativity that characterizes Generation Z or as a coping mechanism on her part. Shashenok simply says she wants to show the world what is happening.

What is beyond doubt is that TikTok is an extremely efficient platform for information. Created in China and launched internationally in 2017, it hosts videos ranging from 15 seconds to 10 minutes in length and has over one billion users. The vast majority are between 18 and 24 years old and use it as their main source of news. At the same time, many traditional media outlets have also set up their own TikTok accounts. The Washington Post, for example, has 1.3 million followers on the platform. The rise of TikTok as a new method of communication has even led the White House to select 30 Tiktokers to spread the message the Biden administration wants to get across about the war in Ukraine.

TikTok is still resisting in Russia, where propaganda reigns supreme. The majority of foreign correspondents left the country on March 5 when a new law was instituted allowing the Kremlin to punish what it considers “fake news” - such as using the term “war” to describe the war - with up to 15 years in prison. Some 15,000 Russian dissidents who have expressed opposition to the invasion of Ukraine face fines or jail terms, according to the latest data from OVD-Info, an independent journalism outlet that is covering the anti-government protests.

While Instagram, Facebook and Twitter have been blocked - evidence of the power of these platforms to question the government of Vladimir Putin – TikTok is clinging on, albeit with severe restrictions: no users are currently permitted to upload new videos or broadcast live. Neither is content on international accounts accessible. However, the younger generations are quick to find ways around censorship and many Russians have managed to sidestep the measures by using VPNs. The use of this technology has increased by 600% in Russia since the Kremlin launched its invasion of Ukraine according to TOP10VPN, a website that tracks VPN usage.

“In Russia, there is a lot of fake news. And most of the people don’t believe that in my country we have a war... My mission is to show the whole world that it’s happening now in real life, and you can see now the war on TikTok,” Shashenok told CNN. “Hi, I’m Russian and although I’m not personally responsible, I want to apologize for what is happening to you and your country,” a TikTok user responded to a post from Shashenok on March 14. In the video, she tells her followers about her evacuation from Ukraine and arrival in Poland after spending 10 hours standing up in one of the trains carrying refugees away from the front lines, and a five-hour wait at the border to cross. She traveled alone. Men between the ages of 18 and 60 are not allowed to cross the frontier, as such her father stayed behind and her mother decided to remain with him. The couple are still in their bunker in Chernihiv.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.