‘Leave me alone,’ the wish that should be considered a right

Freeing yourself from social expectations and distractions – or taking a few minutes out of family life to find some space and introspection – is a healthy practice. It allows you to be at peace and not give up on who you are, or who you aspire to be.

Being alone for 10 minutes a day should be considered a fundamental human right. Or perhaps it should be funded by Social Security, in the interest of mental health and national harmony. Being more alone than ever, of course, isn’t advisable — scientific evidence linking unwanted loneliness with various chronic diseases is solid — but constantly being accompanied by other people’s chatter (real or digital) isn’t good, either. Freeing yourself from social expectations and distractions, while seeking some space and introspection, is a healthy practice. It allows you to be at peace and not give up on who you are, or who you aspire to be.

Aloneliness is a word that some academics now use to refer to the irritation that we feel when we cannot take a few minutes out of social or family life to be by ourselves. Robert Coplan — a psychologist at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada — defines it as the negative feeling that appears when a person cannot be alone for the time they need. “This lack — like unwanted loneliness — erodes our well-being,” he tells EL PAÍS via email. In his research, he finds that this feeling is associated — both in children and adolescents, as well as in young adults — with higher levels of perceived stress, a negative mood and symptoms of depression. A 2022 study that examined the effect of the absence of moments of solitude in several marriages concluded that aloneliness was a fairly accurate predictor of arguments and aggression in couples.

In just over a century, solitude has gone from being idealized by romantic writers and poets, to being a subject of study and epidemiological warning for contemporary sociologists and anthropologists. In English, there’s a subtle semantic distinction between solitude and loneliness. Although both terms appear as synonyms in many dictionaries, they don’t have the same connotation. “Solitude is a place we voluntarily arrive at for a time and from which we can leave. Meanwhile, loneliness is something that happens to us… a negative feeling that invades us when we’re isolated and dissatisfied with our social life,” Professor Coplan clarifies.

In the essay Solitude (1905), Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno already differentiated two types of solitude: the imposed one — “which doesn’t come from an action that we exercise freely” — and the desired one, “a state that we actively seek because it produces well-being.” Coplan notes that there are many reasons for unwanted loneliness’s bad reputation, including its association with poor mental health and the development of several chronic diseases. He cites a recent report by US Surgeon General Vivek Hallegere, which states that chronic loneliness is a health risk that’s equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

“Freedom” is the great benefit that — according to Coplan — science finds in spending time without social interactions. “It allows us to relax, to push our negative emotions [away] until we feel better, to restore and recharge our batteries — which are exhausted from excessive socialization — and to open up the necessary space in our minds so that creativity can explode and problems that once seemed unsolvable can be solved. We can do what we want without the restrictions imposed on us by the gaze of others, to feed our need for privacy and reflection. For many people, this is the only way to concentrate,” he explains.

No one should feel guilty for wanting a few minutes of solitude, even if that desire excludes children, partners, parents, or friends. The expert only sets one condition for taking advantage of it: “The experience will only be positive if we have chosen it.”

Jennifer L. Smith — a researcher at the Mather Institute in Illinois, which specializes in issues related to aging — has found that the power of choice is what determines the way we experience solitude. “We have a positive attitude towards the time we spend alone when we don’t feel forced to give up on our social life and we know that we’ll get it back,” she writes, in an email to EL PAÍS. “Loneliness has a bad reputation, because we’re social animals and we assume that others are unhappy when they’re alone. This isn’t always the case. Additionally, it can feel very lonely to be surrounded by many people,” she points out.

There’s no such thing as a minimum standard time for micro-moments of solitude. Science hasn’t been able to determine why one person would need 10 minutes a day and perhaps another would need half-an-hour. Virginia Thomas — a professor of Psychology at Middlebury College — invites us to “check the pulse of our needs.”

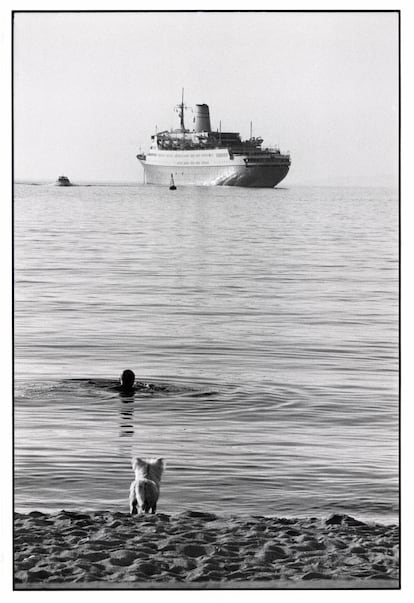

“It’s a learning curve; we learn about ourselves. [We have to find out] if [our irritation] goes away when we go swimming or for a walk, or if what calms us down is disappearing from the family’s radar for a few minutes,” Thomas says, in conversation with EL PAÍS.

There are also those who believe that they don’t need any time for introspection and solitude. These individuals have a real aversion to facing themselves. Tore Bonsaksen — a professor and researcher at the Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences — applies the echo chamber theory to what we think when we’re alone. “We hear our thoughts over and over again, amplified and distorted. And, if we’re alone and also depressed, we will repeat increasingly negative ideas in a loop,” he describes via email. In a series of 11 studies carried out by the University of Virginia and Harvard University, a quarter of the female participants and two-thirds of the men said they preferred an electric shock rather than spending time alone with their thoughts.

“To enjoy solitude, we have to accept that it’s healthy. And, for that reason, we should allow ourselves to take social breaks without feeling guilty,” Thomas reflects. She studies the cultural impact on ways of experiencing solitude. “In the most collectivist societies and families that value and identify unity with harmony, it’s difficult to make people understand the value of spending time alone without anyone getting angry.” Professor Coplan believes that those who need to be alone should let their closest circle know. “What the latest research shows is that these micro-moments of solitude greatly improve relationships. We should be able to say: ‘I love you and I enjoy spending time with you, but I need my space and that will be good for both of us.”

Cultivating positive solitude will help us understand ourselves better and differentiate what really interests us from what we do when we’re simply dragged along by influences and social hype. Some experts believe that it prepares us to make better choices. “It can also help you re-evaluate ‘filler’ friendships: relationships you maintain because you’d rather do anything on a Friday night besides staying at home by yourself, even at the cost of spending time with people whose company you don’t enjoy,” says Angela Grice, a researcher at Howard University.

In a 2021 study, Virginia Thomas discovered that “specific skills” can be developed to enjoy certain doses of solitude, without necessarily becoming a lone wolf. And, in another work that’s still unpublished, she demonstrates that one can learn these skills: in just eight weeks,

a person can improve their ability to enjoy solitude. Among the skills that Thomas describes are the ability to connect with oneself, the wisdom to protect our time and validate the need for moments of solitude, as well as the sense to distinguish, on the one hand, when we’re overstimulated and need to go out for some air… and, on the other, when we’ve had enough of solitude and must seek company again.

“The best of both worlds”

Thomas tells EL PAÍS that science has made it very clear that solitude is a positive experience, so long as we manage to control it and balance it with a social life. “The ideal balance will depend on individual needs. I’ve interviewed people between 18 and 99-years-old and those who live the most fruitful solitudes are those who can relax and enjoy their time alone, because they know that they’ll get their social life back when they want it. They have the best of both worlds.” Most studies show that people benefit more from moments of solitude as they get older and gain more control over their time and greater knowledge about their emotions.

Thuy-vy Nguyen is a social psychologist who runs the Solitude Lab at Durham University, which tests individuals’ resilience to loneliness and their reactions to imagining that no one is watching them. She and her fellow researchers record the benefits of being alone from time to time, including stress reduction, mood regulation and deeper levels of rest and relaxation. Nguyen is also a co-author of Solitude: The Science and Power of Being Alone (2024).

“When people are alone, they take advantage of their freedom to pursue their goals at their own pace, without having to respond to the demands and expectations of the social world. Some people use that space to enjoy their hobbies or unleash their creativity. Others prefer to read, listen to music, or walk in nature,” Nguyen explains to EL PAÍS via email.

Her experiments confirm that some people inhibit themselves from enjoying themselves when they’re alone, especially if they think they’re being watched. “Overestimating the attention other people pay us and worrying too much about their judgment prevents us from relaxing and enjoying ourselves,” Nguyen adds.

The experts consulted for this report believe that we must be “proactive” in the search for micro-moments of solitude that generate well-being. It’s easier than it seems and doesn’t require turning into a hermit or abandoning civilization. “Sometimes, it’s enough to get up half-an-hour before the rest of the family to drink a cup of coffee in silence,” Nguyen suggests.

Professor Coplan finds it useful to eat alone some days at work. However, as a child, he became accustomed to so-called “companionate solitude.” Coplan told The New York Times that he used to accompany his father on fishing trips. They would spend hours sitting in silence, side by side. “It was like being alone without being alone.”

“Spending time alone is crucial for people whose routines involve constant social interaction and the endless demands of other people,” Nguyen emphasizes. “For others, stealing a moment of peace won’t be so difficult — the average adult in the US and UK spends around four hours a day alone — but the problem is learning to manage that space, so that solitude isn’t perceived as a waste of time.”

Bonsaksen thinks that our “long list of passive friends” on social media platforms doesn’t protect us from unwanted loneliness. “It’s just social capital… resources that could be useful at some point. They serve to make people boast about being well-connected, but it takes a lot more connection and interaction with others to not feel lonely,” he writes. In his experience, people who already feel lonely find it “difficult” to connect online with other people and, when they do, those relationships seem “superficial.”

“From the point of view of personal connection, social media seems to work better as an extension of existing relationships, rather than as a space for establishing new connections.”

Bonsaksen also distinguishes between the uses we give to the phone when we’re alone. “Active users chat, post and comment; passive users scroll and look at other profiles. At least one study has linked a passive attitude on social media with a depressive mood that’s often closely linked to unwanted loneliness.”

The phone can be mistaken for that friend who’s always there when everyone else has already left. “It doesn’t rest and, by design, it doesn’t encourage people to rest, either. It sends out constant alerts, notifications, sounds and signals. It’s no secret that, even if we say that we use [social media] platforms, they’re the ones that use us and end up shaping our lives.”

Our precious minutes of solitude could end up contaminated by a bot farm, or sprinkles of digital hate. In both cases, we may end up in a bad mood without knowing exactly why… and, above all, we will have lost an opportunity to be happy. Solitude, in controlled doses, is a powerful tool for well-being. We shouldn’t give up this superpower to anyone.

Translated by Avik Jain Chatlani.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.