A year after the ‘Aquarius’ sea rescue operation, migrants rebuild lives

Over a period of six months, Spain took in 1,000 people who were stranded in the Mediterranean while other EU countries turned them away. These are some of their stories

Ali Hazrat, a Bangladeshi who didn’t know how to cook, now helps in the kitchen of a bistro. Khingsley, a boy who has spent more than half his life in transit, is learning to read in a French school. Diokel, a young man from Senegal rescued by a fishing vessel, is trying to make a living as a day laborer and waits for work every morning on a roundabout.

For a period, Spain became the unlikely destination for migrants who were rejected by Italy and Malta. First there was the symbolic rescue operation by the Aquarius, which took over 600 migrants to a Spanish port in June of last year after Italy and Malta turned them away at the height of the EU migrant crisis. Other rescue operations followed.

Between June 2018 and January, when Spain decided to stop rescue boats from leaving port, more than 1,000 migrants were brought to the country with a dream to build a new life. EL PAÍS has located some of them a year later to find out how they are doing.

Tears at the bistro

Restaurant owner Virginia Texier, who is from France, and her Argentinian chef Nacho Sirven almost cry as they speak about their new kitchen assistant at Le Bistrot in downtown Reus, in Catalonia. When Texier received Hazrat Ali’s resume, there was a note attached: “He has no experience, he speaks very little Spanish, but he is really keen to work.” Texier did not hesitate to hire the 29-year-old from Bangladesh. “He is punctual, he’s always in a good mood, and he’s a good listener,” she says.

Ali has spent just two weeks in an apron and already he has filled his phone with photos of dishes inspired by French cuisine. Beside the pictures, he writes the names in Spanish: “apple jam, stuffed squash…” When Ali arrived at the port of Barcelona on the Open Arms boat on July 4, he could not even read the Roman alphabet, but he is one of a number of success stories among the 60 people rescued on that humanitarian mission.

The chef, who adores him, has occasionally had to hide in the bathroom so that Ali would not catch his tearful reaction to stories about his life. “I am really lucky that our paths have crossed,” says Sirven. “He has taught me to appreciate so many things. When you see it on TV, it is moving, but when it is close to you, it affects you in a whole different way.”

Ali’s flight from Libya was a desperate one. Enslaved in the construction sector, he had no money to get on a boat that would take him to Italy. “I hugged the legs of the trafficker so he would let me on board,” he explains.

Ali now has a 30-hour contract and his pay is less than €900 a month, some of which he lives on and some of which he sends back to his family. “I’m really happy,” he says. “But now I have to help my parents. They are too old to work. It would be good if they could come. Looking after the family is a dream we all share.”

Despite his economic situation, he wanted to pay the €20 for lunch on the day he was interviewed by EL PAÍS.

Excelling in school

Khingsley was just nine years old when he crossed Africa and then the Mediterranean. His journey, which began in 2013, has split his childhood in two. While his stepfather Narcise worked in Libya, Khingsley and his mother Judith spent their days locked up in the house for fear of being abducted by the militias. Even so, as Judith explained from the deck of the Open Arms on June 30 of last year, the three of them were tortured. When they were rescued, Judith cried and begged not to be sent back to Libya.

Just short of a year after their rescue, the family has gone from fearing for their lives to celebrating the grades that Khingsley is getting at school in a town in Normandy, an hour and a half from Paris. “He speaks good French, he’s started to read and write and he has made friends very quickly,” says his mother. “The teachers love him. And he loves going to school.”

The family of three first lived for a while in Manresa, but learning both Catalan and Spanish proved too difficult. Impeccably turned out, Judith explains that she has been given refugee status but she is still waiting for the outcome for the rest of the family.

Narcise, who is from the Central African Republic, wants to work in construction while Judith, who is from the Republic of the Congo, wants to look after children or the elderly. “We are very happy and we thank God for saving us,” she says. “We will never forget Spain because it offered us the chance of a new life.”

The grandfather

Houssein Karrit became known on the deck of the Open Arms as “the grandfather” because, at 59, he was the oldest of the 60 migrants rescued by the humanitarian ship at the end of last June. At that time, he was chain smoking and smiling with his eyes, hiding his broken teeth. But he was not the rough man he seemed to be from afar. Now, almost a year later and able to speak some Spanish, he is happy but fragile; he is a father without his children.

“I never imagined I would spend so long without seeing them,” he says, showing his wife’s Facebook page, which is where he watches them grow up. “The little ones don’t even know me.”

Karrit went to Libya in 2012 after war broke out back home. His smallest son was just four months old at the time and the middle child just over a year. His plan was to work, make some money and join his family the following year. But, like so much else, things did not work out that way. He has another two children who are already grown up and in Germany, having left Syria before him.

Karrit is allowed to work while he waits to see if he will be offered asylum. He has just finished a three-day trial fitting the tiles on a swimming pool but did not get the job. He does not even know if he will be paid for the trial, but he does not complain. Things that are taken for granted in Spain, such as being able to phone 112 for an ambulance, are a great comfort to him. “I finally feel as though I’m being treated as a person,” he says, speaking at a Turkish restaurant in Reus. “I feel at peace. The Spanish have given me confidence and peace without wanting anything in return.”

Dreams of asylum

Vivian, a 24-year-old Nigerian woman, was sold, abducted and raped in Libya. She was forced to work as a prostitute to pay the €6,000 price tag on her freedom. She became pregnant and was forced to have an abortion. Her desperate flight across the Mediterranean ended on the deck of the Aquarius with 629 others on June 9 of last year. Any talk of Libya can still make her tremble with fear, but she is now studying Spanish in Valencia and is training to be a waitress at a hotel while awaiting the outcome of her asylum application. On weekends she goes to church, then takes a bus to the beach with a group of female friends who were with her on the boat. “I only go in [the sea] a bit,” she says. “I splash water on myself because I don’t know how to swim.”

Every time she thinks about her new life, she heaves a sigh of relief. But at the same time, she is anxious because she is far away from her children, the oldest of whom is eight and the youngest six and currently ill. “If the government decides to help me and look after me, they might give me papers and a permit to bring my children here,” she says. “It would make me very happy. We would live together and I would work cleaning hotels and houses and wouldn’t have any more problems. But if they say no, I don’t know what will happen because I have nowhere to go. I hope God doesn’t allow that to happen.”

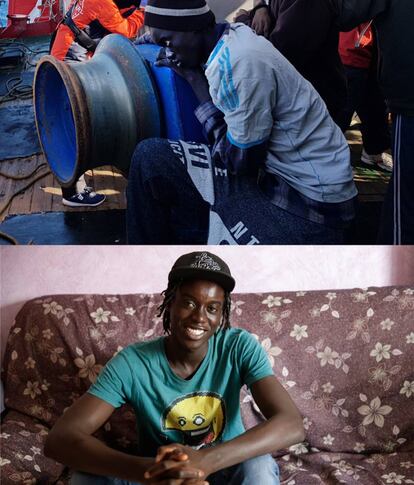

Saved by a fishing boat

Diokel Diop, a young Senegalese man, must have seen his life flash before his eyes when his rubber dinghy crossed paths with a Spanish fishing boat and a Libyan patrol ship on November 21, 2018. Now 19 years old, he lives in a rural house with seven other migrants from Senegal in a small town in the region of Murcia.

He has applied for asylum but has left the center in Madrid where he was first taken in. Still without a work permit, he waits on a roundabout to be picked up by local farmers to cut lettuces for €5 an hour. His uncle Abdoul, who arrived in the Canary Islands during the 2006 so-called cayuco boat crisis, tries to help him out financially. “If he had asked me, I would have told him not to come,” Abdoul says affectionately. “Life is very hard here.”

The rescue operation involving Diokel Diop had an element of David and Goliath about it. When Pascual Durá, the captain of the Santa Pola-based fishing vessel Nuestra Madre Loreto, spotted the migrants on Diokel’s boat rowing frantically towards him, he threw out a rope. Diokel and 11 others threw themselves into the freezing water and scrambled aboard the Nuestra Madre Loreto. “I would rather have died than go back to Libya,” says Diokel, who was enslaved there for a time.

Durá’s decision put Spanish authorities in a difficult situation. For 10 days the captain waited offshore while Italy and Malta refused to let him dock. In Madrid, the same Socialist government that had welcomed the migrants rescued by the Aquarius now told the fishing vessel to take Diokel and the others back to Libya. The crew refused to obey, and set sail for Alicante instead. Eventually, Malta relented and agreed to allow the boat ashore on the condition that those aboard would be taken directly to Spain.

Diokel still has nightmares about the Libyan sea, but this has not prevented him from hatching a maritime plan for a future when he has his papers. “I’m going to get in touch with Pascual so he can take me on as a fisherman on his boat,” he says.

Chronicle of 2018 rescues

June 17. The Aquarius arrives in Valencia with 630 migrants aboard.

July 4. The Open Arms enters the port of Barcelona with 60 people.

August 9. Algeciras lets in 87 people rescued by the Open Arms.

November 21. The fishing vessel Nuestra Madre Loreto rescues 12 people. After 10 days of indecision, Malta agrees to let the boat dock and 11 migrants are subsequently taken to Spain.

December 28. The Open Arms returns to Algeciras with 308 people, including 147 minors.

January 8, 2019. The government stops Spanish NGO rescue vessels from leaving port anymore.

English version by Heather Galloway.