The unsung heroes of the impossible mission to rescue Julen Roselló

The hundreds of people who helped locate the two-year-old in a 110-meter-deep borehole are struggling to come to terms with their experiences

At a depth of 72 meters underground, the silence can be terrifying. Even more so when you can sense what is on the other side of the rock you are battling to get through. When the wall finally falls with the last blow, the sweat from your efforts turns cold. And the thread of hope that had lasted for 13 days snaps in just a second. “Right then your heart sinks,” explains Francisco Maturana, a Civil Guard mountain rescue expert. It was he who found Julen Roselló in the early hours of Saturday, January 26, 299 hours after the two-year-old fell down a borehole in southern Spain. He didn’t survive the 71-meter drop. The sadness of Maturana was accompanied by the relief of everyone working on the rescue: “We’ve finally found him.”

We always thought that there was a small chance that he had survived

Engineer Ángel García Vidal

The first firefighters and emergency crews who arrived on the scene of the illegal borehole all asked themselves the same question: Could a child fit in that well, which measured barely 25 centimeters across? Their doubts did not last long: they believed the story that the youngster’s parents told them. Logic suggested that the child could not still be alive after such a huge fall, but the rescue crews hung on to the slim hope that they could still get him out of there.

“We always thought that there was a small chance that he had survived,” the engineer Ángel García Vidal explains from his office in the neighborhood of La Malagueta. He is still digesting the emotions from the 13 days that he spent working against the clock, leading the engineering aspects of the rescue effort. Like him, other people who took part in the search operation have had a difficult week. It will never compare with the grief of Julen’s parents – who also tragically lost their first child, aged three, to a heart condition – but the experience will never leave them.

Once the rescue effort got going, they could not rest. Days later, their minds won’t let them either. They are shattered. They want to put the experience behind them, but their conversations run on and on, with words that they had been holding back now gushing out of them. They need to unburden themselves. “No one can prepare you for something like this,” says Francisco Ruiz, the head of the Eastern Andalusia Emergency Group (GREA), a man with years of experience in similar situations, including the search for Gabriel, a child who went missing in Cabo de Gata natural park a year ago.

García Vidal, the engineer, was one of the key figures in Totalán, the small municipality where the accident happened. He spent 20 hours a day on the hillside throughout the search operation, just going home to shower and rest for a few minutes in the company of his wife and children. “The situation was on such a scale that it trapped you completely, both physically and mentally,” he explains, smoking one cigarette after another. “You don’t want to do anything except solve it.”

García Vidal was trusted by the media outlets covering the rescue in a way that they never would have trusted a politician. His face reflects a weariness greater than he will admit to. On the table there are papers filled with undelivered projects, the deadlines for which have long passed. One of them shows an aerial view of the search area, Cerro de la Corona.

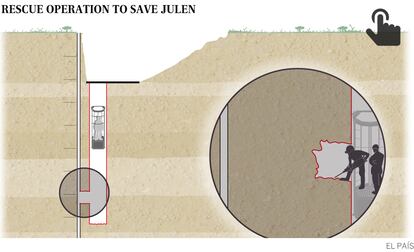

Dozens of notes reveal the detailed analysis carried out in a bid to find the solution to a problem that was tackled by specialists from all kinds of different disciplines. How do you find a child at a depth of 72 meters in the shortest time possible? The easy answer was to carry out work that would have taken two years under usual circumstances. The difficult part was to compress that work into two weeks.

Another variable complicated the operation even more. There was never any evidence to prove that Julen was under that plug of earth that cameras had found just hours after he fell into the hole. But of all the places he could be, it was the most likely. That was why the area was treated with particular care. Even a seismograph was used, to monitor whether the vibrations from the work that was going on outside could cause landslides.

The entire operation was designed to get to that particular spot. No one wanted to think that he could be even deeper down, at the bottom of the borehole, which had been drilled to a depth of 110 meters.

The first idea was to drill a horizontal tunnel, but the earth moved during the first probes. The instability forced the teams to go for the next option: a shaft running parallel to the borehole. Machinery to excavate the vertical tunnel arrived from Guadalajara in record time. But the terrain threw up a series of problems, proving one of the maxims of geologist Francisco Manuel Alonso: “It’s easier to get to the moon than to the center of the earth.”

Alonso, a professor from the University of Huelva, arrived in Totalán on January 20. He was one of five geologists who helped with the rescue, and he played a key role. Every day he would meet with members of the rescue team at the Hotel Rincosol. It was a kind of group therapy, where the attendees would find mutual support and analyze the details.

Alonso also helped the Hunosa Mining Rescue Brigade whose members had come down from northern Spain to understand what they were going to find underground in this part of the country. And he was proved 100% right with his predictions, even down to the inclination of the rock. The members of the brigade now see him as another member of their team. He himself sees his 30 years of experience as time well spent, and explains that he is not the same geologist he was before he went to Totalán. On his desk is a small piece of quartzite that was a gift from Sergio Tuñón, the head of the miners, as a reminder of an experience that he never wants to go through again. Next to it is a piece of the drill bit from the boring tool used to dig the rescue shaft. Made from an alloy of diamond and tungsten, it attests to the hardness of the ground.

The seam of quartz that was found when digging the shaft was both a problem and a help. If breaking through it was an ordeal, its hardness guaranteed that the tunnel would not collapse while the miners were working underground. Safety was always one of the priorities when planning the rescue. It was the word that the chief firefighter, Julián Moreno, repeated the most during the efforts. There were around 300 people working on the site, and there could be no more accidents. One was enough.

No one can prepare you for something like this

Francisco Ruiz, head of GREA

But that was easier said than done: in Cerro de la Corona there were specialists, engineers, technicians and Civil Guard officers. There were also staff from the 112 emergency services, from the GREA and Civil Protection. The head of the volunteers working for the latter organization, a member of the military named Daniel Alcaide, was an essential part of the logistics of the operation. The demand for coffee during the 13 days of work was “huge,” he notes, but his work went much further than simply procuring liquid refreshment, distributing the food and even the tobacco donated by nearby residents. He always had a smile for his team, even when the situation was getting them down. He is still calling his volunteers on a daily basis. Their professionalism was “incredible,” according to Eduardo Díaz from the GREA.

The experience wasn’t easy for the miners,either, as they are not used to being in the spotlight. And while they are always working in extreme conditions, these are completely different to those to be found in Totalán. Every time they emerged back on the surface, their faces expressed desperation. “That rock is so hard,” they said, while taking in the clean air once more.

The miners eventually needed support from the Civil Guard’s TEDAX explosives unit. Three of the team’s members were in Totalán from January 19 onward, waiting until they could serve a purpose. That purpose came on the last day, when they helped with four small charges that were used to break the rock. They had already saved lives with the same operation during other rescues. “But we had never had this kind of exposure,” explains Óscar Real, a member of the team.

The last explosion was just 70 centimeters from where Julen was thought to be. That was too close. “It was the most important one,” adds Captain José Emilio Caba from TEDAX.

After the explosions, a Civil Guard mountain rescue specialist always accompanied the miners down below. He went down the shaft to assist, but also to serve as a judicial police officer to record any evidence of the minor’s presence. One of these specialists was Nicolás Rando, whose son would ask him every morning if today would be the day that they would pull the youngster out of the borehole.

At 1.25am, the rescue team did just that. Many of the rescue crew members, who were located around 200 meters from the central site of the rescue effort, heard the news when it was broadcast on Televisión Española an hour later. It was a slap in the face for all of them. The faint hopes that Julen was still alive were dashed. Fatigue soon set in, and the cold took hold. The machines were stopped and sobbing could be heard.

But soon silence reigned. It rose from the depths to bring reality back to a team that did not want to give up hope until that moment. No one wanted this ending, just like no one wanted to abandon Julen in the depths of the earth. At least, with the sad conclusion to the efforts of hundreds, the grieving process could begin.

English version by Simon Hunter.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.