Church abuse victim: “He would talk with my parents, then come up to my room and touch me”

Manuel Vilar Herrero recounts the assaults he suffered as a child at the hands of a priest who was “worshiped” by his mother and father. The following testimony is one of several making up an EL PAÍS series exposing decades of offenses by the clergy

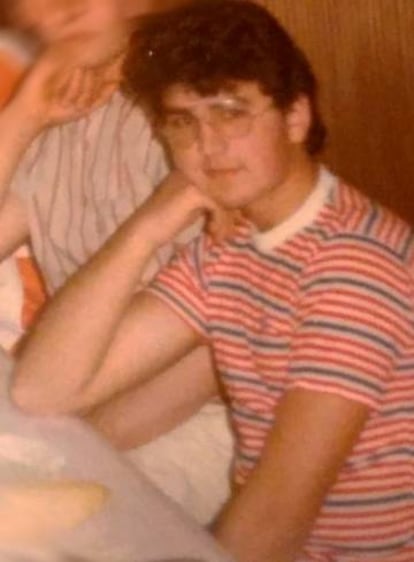

Artana in the province of Castellón is a deeply religious parish of 2,000 people, but for years it has been hiding a dark secret, one that Manuel Vilar Herrero decided to expose. “I was victimized by the priest,” says Manuel, 50, referring to Antonio Gil Gargallo. “It started with fondling and kisses on the neck. Then he went on to touch my behind and my genitals. You could see him getting excited. He would end up rubbing himself against me, fully dressed, until he came in small convulsions.”

The abuses began in 1982 when Manuel was 14. “We had finished EGB [primary school] and we had to leave the village for BUP [secondary school] in Nules. At that time, the priest chose a number of us to come to his home to speak about morality. They were informal meetings and we would watch a film, and we could smoke and drink a bit of alcohol. It was at these meetings that the abuse started,” he says.

“He made us come into a room for a kind of confession and that was where everything happened. I stopped going, but then he asked two or three of us if we would keep him company one night. I avoided that by saying I had homework. That’s when he started turning up at my house. He would talk for a while with my parents, then come up to my room and touch me again. It was awful. Telling my parents about it wasn’t an option. They worshiped him,” he explains.

“The abuse went on for more than a year until one day I stood up to him. He acted offended and stopped coming. Later, I brought the subject up with several friends and I realized that there had been more incidents. No one had said anything until then. But still nobody wanted to speak about it. Even now, everyone looks the other way, even though I have sometimes mentioned it in public. The town doesn’t want to accept what happened. The worst of it is that they knew something was going on. I first heard rumors when I was doing my first communion. But I didn’t take any notice. I thought it wasn’t possible. Until it happened to me.”

Life at high school allowed Manuel to make new friends and process what had happened. “I was very young but it didn’t take me long to realize that it was very bad; that you can’t abuse a child; that it was a crime. I distanced myself from the Church for good.”

They even said that he had fallen in love with me as though it were my fault

Abuse victim Manuel Vilar Herrero

A few years later, while speaking to an older friend, Manuel mentioned his sudden loss of faith. “He was surprised and asked why, so I told him about the abuse,” says Manuel. “He said that I had to speak out about it and he took me to see another priest who was from the village and who was in the diocese.

“And so began an agonizing stream of interviews,” he says. “I had 10 meetings with priests and people from the diocese. We saw each other two or three times within a short period of time and then there were months when nothing happened. The bishop came twice. They made me repeat what had happened again and again. They even said that the priest had fallen in love with me as though it were my fault. And that went on for more than a year.”

Finally, they offered to set up a meeting with Antonio Gil Gargallo, which never materialized. “After that, it was over. I blamed some of those involved in the meetings. They were adults and they should have come to the aid of a child – an adolescent who was seeking help. But they talked to me about some sort of pact of silence that is still respected,” says Manuel, who is now an ethnologist and lives in Valencia. Single and without children, he says he is happy in spite of everything. “They haven’t robbed me of that,” he says.

What did happen, however, was that Antonio Gil Gargallo, who died several years ago, was sent from Artana to his hometown of Montán, also in Castellón, a parish with less than 300 residents. But there was never any public explanation for the fact he never returned to Artana. “I imagine it was because of me, but nobody bothered to tell me,” says Manuel.

The diocese of Segorbe-Castellón maintains that it has no information on the case

Enrique Vilar Villalba, from the Popular Party (PP) and who has been mayor of the village for the last 20 years, claims he never heard about the abuse. “If it happened, they are reprehensible acts but it never reached my ears,” he says.

The diocese of Segorbe-Castellón, which has 146 parishes and 200 priests under its supervision, maintains that it has no information on the case. “The decision must have been taken by the bishop and communicated verbally,” says a source from the diocese. The bishop at the time, Josep Maria Cases Deordal, died in 2002. The same source recognizes that what happened should have been subject to a canonical penalty.

“The priest was removed from a very important parish and sent to a much smaller one, which was also his hometown, and that is not common. Everyone knows that no one is a prophet on their own turf,” says the source. “According to the facts, the move included a severe verbal warning from the bishop never to return to Artana.”

Asked about their response to the complainant, those currently responsible for the diocese say, “Since the papacy of Benedicto XVI, the Church has more effective tools to deal with cases like this.”

English version by Heather Galloway.