Spanish Defense Ministry to release secret documents on Civil War and Franco dictatorship

Thousands of files on military operations, concentration camps and the intelligence agency are set to be made available to the public following an internal report

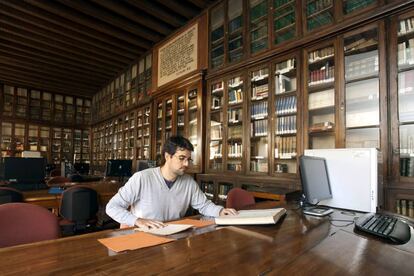

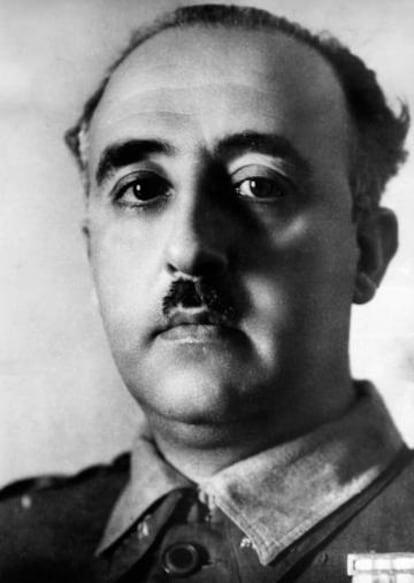

Spain’s Defense Ministry has taken the first step toward making secret military documents from the Spanish Civil War and dictatorship of Francisco Franco available to the public. The Commission for the Classification of Defense Documents approved a report that recommended that Defense Minister Margarita Robles authorize general access to pre-1968 documents regarded as confidential and kept in the General Military Archive in Ávila.

The decision only concerns the archives in Ávila, which is just one of eight historical archives

Thousands of these documents hold the key to understanding Spain’s recent history, including previously undisclosed information on military operations during the war, and repression under the dictatorship (concentration and labor camps). There are also documents on post-war activity, such as the fortification of the Pyrenees and Morocco, when Franco was fearful of a post-war invasion, as well as bulletins from the central intelligence agency.

The documents in question date from the coup d’état in 1936 until 1968, when the current Official Secrets Act was passed. According to the report from the Commission for the Classification of Defense Documents, the army has already confirmed that releasing these documents will in no way compromise state security.

The report does not indicate how many documents will be released into the public domain, but in 2011, the then-defense minister, Carme Chacón, said that 10,000 files might be declassified. Experts, however, believe the real figure could be three times as high.

Analysis work carried out in 2011 has oiled the wheels for the current release of these documents. Chacón left the job all but done, but was interrupted by early elections. Her successor Pedro Morenés from the right-wing Popular Party (PP) halted the operation, maintaining that he had other priorities that took precedence over the release of documents that had “no interest other than to feed media noise.” Morenés argued that misrepresented information from another era might stir up trouble with their political partners.

Unlike Chacón, the current defense minister is not expecting to actually declassify any document. The commission’s report concludes that the Franco-era Official Secrets Act, while forming part of the current legislation, is not retroactive. This means that no document prior to April 28, 1968, when the law came into force, is legally classified as secret and consequently no declassification is necessary.

Opposition

The report adds, however, that there is a provision in the historical heritage law that prevents the public from accessing documents whose release could threaten the security and defense of the state, even if they are not legally classified. In such an event, consultations can be authorized by the head of the department in charge of the archives – namely the minister of defense.

In this way, the Defense Ministry hopes to avoid absurd situations, like the time when army officials banned access to all documentation bearing the stamp of confidentiality, including many historical documents that were already available to the public during Franco’s dictatorship – a move they were forced to backtrack on by protesting historians.

According to commission’s report, the Official Secrets Act is not retroactive

In reality, this interpretation was not dissimilar to that of the PP, which believes that the documents on the Civil War and the subsequent repression are still confidential and should not be made public until at least 2022.

While this is a first step forward, the current decision only concerns the archives in Ávila, which is just one of eight historical archives under its authority.

Addressing a shameful situation

Public access to military documents issued before 1968 constitutes “a step forward in a shameful situation,” according to Juan Carlos Pereira, a professor of modern history at Madrid’s Complutense University. In recent years, the Spanish archive system has become increasingly less accessible and lacking in resources, forcing researchers to look for information abroad that is denied to them at home.

The validity of an obsolete Official Secrets Act, which has no fixed dates for declassification, and the conflicting opinions on the release of material issued before 1968, has meant “access to a document often depends on the civil servant on duty that day,” says Pereira.

The historian points out that the archives that will now be available to scholars were already studied for potential security threats during former Defense Minister Carme Chacón’s period in office. And as no problems were flagged up then, he expresses his regret that eight years have passed with no progress made.

He now hopes that the move toward releasing the military archive in Ávila will soon be extended to include the other seven historical archives under the ministry’s authority, and that this example might be copied by other ministries, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation which, in October 2010, with the approval of the Spanish Cabinet, classified as confidential almost all diplomatic correspondence, without taking into account when it was issued, turning the study of Spain’s foreign policy into a Herculean task.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.