Orphans by White House decree

Casa Padre, the largest US shelter for undocumented underage migrants, holds hundreds of kids separated from their parents by the new brutal “zero tolerance” policy

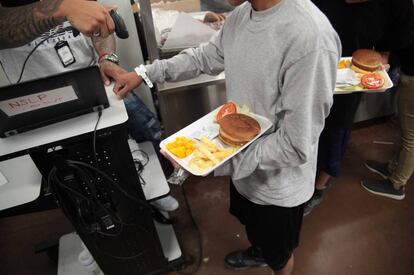

At the holding center of Casa Padre, some children smile while others stare into space, overwhelmed by the sudden reality they find themselves in. They live in a bubble: they eat three times a day, have a bed, clean clothes, medical attention, a play room, a movie hall... but their experience at Casa Padre masks a trauma from the dangerous trek to the US, and tries to sugarcoat the fear and anxiety for their uncertain future.

Casa Padre, an old Walmart store converted into a gigantic children’s shelter in Brownsville, TX, next to the border with Mexico, houses these kids as well as their trauma and anguish. In a few days, the almost 1,500 undocumented minors in the center – the biggest of its type – will know whether they will be deported or if they may stay until their legal situation is resolved. And a fourth of these children are gripped by a different fear entirely, as they came into this country with their parents but were separated from them at the border.

1,995 children were separated from their parents between April 19 and May 31 alone

These kids are victims of the Donald Trump administration’s new “zero tolerance” policy. Since April, any adult caught entering the USA illegally is prosecuted and taken into federal custody; if they are accompanied by a minor, this minor is transferred to the social services. The system is opaque, and its reach is unknown so far. It is not unusual for a parent to be deported while their child remains in the US.

A total of 1,995 children were separated from their parents between April 19 and May 31 alone as they entered the US at official border crossings, based on the numbers collected by Associated Press. This excludes all of the immigrants that reach the country through unofficial points of entry, such as crossing the Río Grande on rafts.

The new US directive has a clear goal: to scare migrants into not coming. However, so far there has been no deterrent effect powerful enough to stop immigrants – primarily from Central America – from journeying to the US in search of a better life.

Additionally, there is no precedent for a policy of this magnitude. The Republican administration is running out of beds, and beginning to transfer adult detainees into prisons; there are even plans for creating tent cities on military bases. All the while, Trump has expressed that he “hates” seeing these families getting separated and falsely blames Democrats for “forcing him to comply with the law.” The reality is that his government is acting unilaterally.

The issue has become so contentious that the Human Rights Committee of the United Nations has called the new policy a “serious violation of children’s rights.” Multiple social organizations are trying to stop the policy in court, and there are more voices denouncing the immorality of the world’s richest country, a country born out of immigration, now acting so cruelly to migrants.

Casa Padre serves as a case study of the situation in one of the world’s most unequal borders. “We are dangerously close to our occupancy limit,” warns Juan Sánchez, the founder and president of the Southwest Key Programs organization that manages the center under a contract with the Department of Health and Human Services. “It has never been this full,” he explains to a small group of journalists during a visit to the center last Wednesday, during which they are not allowed to speak to the children.

“Good afternoon,” some say. “Everything’s okay.” Others keep silent or even seem uncomfortable at being observed like caged animals of a rare species. The children are dressed in t-shirts and shorts, and many wear rosary necklaces.

That day the center was sheltering 1,469 minors, just 28 below the limit. They arrived here after spending a maximum of 72 hours in a police holding center. All of them are boys between 10 and 17, and at least 70% of the boys arrived in the US completely alone on their journey from Mexico. But the ratio of minors traveling with their families and separated at the border is growing, too. On average the boys spend 49 days there, while the national average is 56 days.

The US government has 11,351 minors in its care in hundreds of centers, according to the latest data, which did not specify how many had been separated from their relatives. The number of children in custody grew 20% between April and May. The minors abandon the centers once they have found a family member in the US or a foster family is found. The children will be with them until a judge decides whether they can stay or not in the US. However, social services announced that they had lost 1,500 children when their guardians would not answer the phone. Many speculate that they do not answer because they too are undocumented immigrants, or because they want to avoid presenting the child to a judge.

Casa Padre is saturated. It opened in 2017 after an old abandoned Walmart superstore that took up 2.3 hectares was revamped. On the day of the visit each of the 313 rooms held four beds in the beginning but a fifth cot was being added due to the amount of kids they have to shelter. Half of the boys go to classes in the morning while the other half goes in the afternoon. At each meal, long lines form for food. Due to last year’s decrease in immigration in the wake of Trump’s policies, Southwest Key Programs was forced to fire some of its workers, but now, due to the sharp increase in numbers of migrants, they are in need of dozens of new employees.

On the walls of the rooms and hallways hang motivational posters and patriotic posters. “Imagine the possibilities of your life,” or “America, the beautiful.” There are murals with quotes from different US presidents – even from Trump. It looks like a summer camp. But only superficially, as the details show how the minors are not free. Each one wears a bracelet tag. The employees wear earpieces and they supervise every movement. On the walls one can find the “rules of behavior.” The boys can only spend two hours in the yard, and they have a right to two calls a week. When a minor arrives, they are isolated for 72 hours with medical supervision. The complex is a bunker, wrapped in an air of secrecy, surrounded by fences and security guards.

Casa Padre is located on a typical American suburban avenue, surrounded by fast food joints and gas stations. Life goes on around the center despite the stories of the almost 1,500 children in it. Omar Agustín Rodríguez, 38, does know about the complex, as he helped install the air conditioning. “I think it’s good, they help them and repatriate them,” he says, sitting inside the McDonald’s next door. Like many of the people here, Omar was born in Matamoros, Mexico – separated from Brownsville by the Río Grande and a six-foot fence. He emigrated to the US in 2000 and now has permanent residency status. He came in search of a better job and safety. He detests the forced separation of families and commends the immigrants. “I see them suffer and yet they keep fighting. I admire them,” he says.

English version by Andres Cayuela