“Literature is not incompatible with anything, not even politics or war”

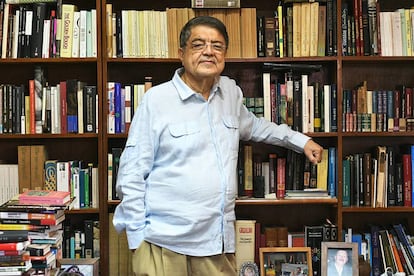

Nicaraguan writer Sergio Ramírez talks about his craft and his role in Sandinismo as he prepares to receive the Cervantes Prize

Nicaraguan writer and intellectual Sergio Ramírez, 75, has arrived in Madrid, where he will accept the Cervantes Prize for literature. As he waits for his three children and eight grandchildren to join him, he wonders how his own parents might have felt to see him honored with the prestigious Spanish-language literature award. “They would have been happy,” he says. “My father was not a learned man but he was sensitive and unaffected. He supported Somoza, but he was a good man. He wasn’t tainted by the wickedness of the regime.”

Ramírez is referring to the family dictatorship that he himself rose up against as one of the leaders of the left-wing Sandinista Front. His role in its overthrow would prompt his mother to remark to his sister, “What is Sergio doing wasting his time with that, if he is a writer?”

After the fall of the Samoza regime, Ramírez served as vice-president, a position he held between 1979 and 1990. Five years later he quit Sandinismo, disillusioned with the slide into authoritarianism of his own party and its President Daniel Ortega.

The author of novels such as Divine Punishment, Margarita, How Beautiful the Sea and Nobody Cries For Me Anymore, he has just penned his memoirs, Adiós Muchachos: A Memoir of the Sandinista Revolution, in which he talks about his revolutionary years.

Central America is a region that boasts about its cultural identity but is forgotten in literary terms

Question. In Adiós Muchachos, it sounds like you were postponing your own literary calling.

Answer. I started writing at 16 but I hadn’t decided yet that I wanted to be a writer. What I did know is that I didn’t want to be a lawyer.

Q. Yet you studied Law and then left for Costa Rica.

A. For the Central American Higher University Council.

Q. You left there in 1973 and went to Berlin with a grant to write a novel.

A. They told me I was crazy, but I had decided to take the literary route. Then I was offered work in Paris because they were about to open the Pompidou Center, but I came back to Nicaragua. For the revolution.

Q. And the Berlin novel?

A. To Bury Our Fathers was published, but I didn’t bother with it. It was published in Venezuela and the copies were left in the warehouse. When it was entered for the Rómulo Gallegos Prize, Carlos Barral read it because he was on the jury. He fought for it and revised it. And as we were in the middle of the ‘Boom’ [literary movement in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s], it was published and translated into many languages.

Q. For those writing in the wake of the ‘Boom’, did it feel more like a door or a wall?

A. An impenetrable wall. But I made the most of the literary doors that were opened to me. They [the members of the movement] weren’t a group, and those of us who came afterwards such as Antonio Skármeta, Alfredo Bryce Echenique or Manuel Puig weren’t either. Later, circumstances such as the Sandinista revolution meant I went from treating them as mentors to getting personally close to them.

Q. Has being Nicaraguan been another obstacle? Compared with Mexico, Colombia and Argentina, Central America seems to be off the radar.

A.It’s true that Central America is a region that boasts about its cultural identity but is forgotten in literary terms, despite having produced writers such as Rubén Darío, Miguel Ángel Asturias and Ernesto Cardenal. It’s not that it doesn’t have influence. I became Central American in Costa Rica.

They told me I was crazy, but I had decided to take the literary route

Q. What is the hallmark of a Central American identity?

A.The culture. The region has a lot of problems with violence – integration has worked very badly and land boundaries are still being fought over in court. But in cultural terms, it has got there.

Q. What was the response in Central America to you winning the Cervantes Prize?

A.It was received as their own in Costa Rica and Guatemala and I was very glad about that. The Cervantes Prize is a brand and although people are not familiar with literature, it really resonates.

Q. Has the Nicaraguan government congratulated you?

A.Not yet.

Q. Will the Nicaraguan Ambassador to Spain go to the award ceremony?

A.I don’t think so. But I would love it if he did. It’s my country.

Political swings and roundabouts

Sergio Ramírez is as passionate about politics as he is about literature. When asked if he believes the Bolivarian period is over in Latin America, he retorts, "You mean Chavismo? I think so. We have just witnessed Evo Morales standing alone at the OAS [Organization of American States] summit … Daniel Ortega didn't even arrive. The coup de grâce was given by Lenin Moreno in Ecuador when he called a referendum to eliminate indefinite reelection, which is a characteristic of 20th century neo-socialism. Some might say that we are living through a right-wing swing in Latin America. But we aren't. It's the sanitization of democracy. Why is there no center-left government in Chile? Because they couldn't present an appealing candidate, not because people had decided that the left shouldn't exist. Opportunities are still there for the future. We are not used to the idea that alternating is part of democracy."

Q. Doesn’t the government forgive you for criticizing its policies?

A.They equate criticism with treason. A democratic government doesn’t have any reason to shut the opposition up because the opposition is part of a democracy.

Q. When did you last see Daniel Ortega?

A.In 1999, at a friend’s birthday party. We chatted. Just small talk.

Q. You had just published Adiós Muchachos.

A.Yes, and I asked him if he had read it and he said he hadn’t.

Q. Ortega doesn’t come off too badly in the book.

A.That’s what I told him. I said, ‘You’ll see that I wrote about you with affection.’ He laughed in disbelief.

Q. Has he changed?

A.He’s now a militant Catholic. I knew him as an atheist.

Q. In the book it says that he has the habits of an ex-convict. Did you hang on to any habits that came from your underground days?

A.None. It was more like I acquired certain habits in government. It was inevitable. I was there for 10 years. I always had people around me and they would even pack my case. The first time I came to Spain, it was in 1990, after losing the elections. I wasn’t used to handling money and I went with some friends to the Plaza Mayor and shocked them by handing over a massive tip. I didn’t miss that life but it felt strange to be in the street flagging down my own taxi.

The Cervantes Prize is a brand and although people are not familiar with literature, it really resonates

Q. One of your most famous novels, Divine Punishment, was published in 1988 during the US-backed Contra counter-insurgency.

A. The idea of not being a writer anymore terrified me. A friend told me that I would save time with a computer and I said, ‘What’s that?’ I bought a tiny IBM in Canada but since it had American parts I wasn’t allowed to bring it into Nicaragua because of the embargo, and so it arrived via Madrid. Like a pianist, the first thing I did was to try out my fingers by writing a short book about my relationship with [Argentinian novelist and one of the founders of the ‘Boom’] Julio Cortázar and musings on the revolution called, You are in Nicaragua. That gave me the feeling I was getting back to the craft.

Q. But Divine Punishment is a long novel.

A. My longest. I used to get up at four in the morning. Literature is not incompatible with anything, not even politics or war. I wrote Margarita, How Beautiful the Sea after I was beaten in the elections and sliding into debt.

Q. Those two novels have a complex structure. Did you never consider resorting to the language of socialist realism?

A.I never entertained the idea that the simpler the language, the more people will get it. My experience is that as time passes, more people read your books. And they read them better. The young people of today understand them better than 30 years ago. I hate the idea of writing in a dumbed-down way so that the people will supposedly understand.

Q. Your last novels speak of the ethical catastrophe of current Sandinismo.

A. In Nicaragua, the revolution is a thing of the past, a rhetorical fact. Official politics ignores it because even Sandino’s original rhetoric seems offensive. The indifference to money is a severe criticism of what is happening now. Seventy percent of Nicaraguans are under 30 and no one remembers.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.