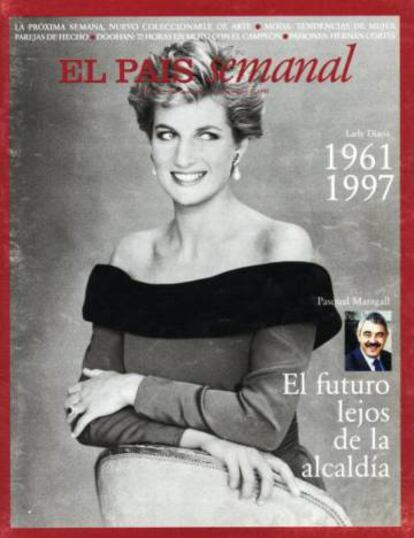

Remembering Lady Diana’s final hours

EL PAÍS columnist Sami Naïr was working in the French interior ministry the night the Princess of Wales died in Paris

“I touched her face. She had the face of an angel. I thought: The Angel of Death. Very beautiful,” recalls one of the last people to have seen Princess Diana alive.

An ambulance had just brought her into Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris in critical condition, following a violent car crash inside the Pont de l’Alma tunnel. She was 36 years old.

For years, Sami Naïr said nothing about the events of that night

The speaker was, back then, a 51-year-old intellectual who had temporarily gone into politics. On that summer night, he was the highest-ranking official at the French Interior Ministry. On August 31, 1997, he was on duty when he received a telephone call: there had been an accident, and it looked like there was a celebrity among the victims.

For years, Sami Naïr said nothing about the events of that night. His position at the time, as adviser to Interior Minister Jean-Pierre Chevènement, entailed a duty to preserve the secrecy surrounding a period of just a few hours that would later spawn a multitude of wild conspiracy theories.

It was a little-known episode in the life of this essayist, philosopher, sociologist, university professor, politician and EL PAÍS columnist.

But his name crops up in some of the last testimonies of Lady Di’s last hours – a confusing, alcohol-infused period of time that ended in a car chase to get away from paparazzi who wanted a shot of the celebrity with her lover Dodi Fayed, the son of an Egyptian billionaire. Also in the car were a bodyguard and the chauffeur, who had had too much to drink.

Naïr has not forgotten those hours in which he held the responsibility of crafting the French state’s official response to an unexpected crisis whose effects are still being felt two decades later.

Diana Spencer, who came from an old aristocratic family, had married Prince Charles, heir apparent to the British throne, in 1981. She was 20 years old; he was 32. It was an unhappy marriage from the start, but like the biographer Tina Brown notes in The Diana Chronicles, “happily ever after” will never sell as well as “everything has gone pear-shaped.” Not for the media and not for the public in general. The story of the Princess of Wales was a reality show from day one.

The stars of the show were, on one hand, a royal heir with stiff manners and his equally starchy clan – a bunch who felt uncomfortable with the mass media and celebrity culture, and who preferred to remain ensconced in their archaic ways and traditions. On the other, a woman who quickly learned how to handle the media, with little formal education and who considered herself not too bright, but who oozed emotional intelligence and empathy. “The Queen of Hearts” and “The People’s Princess” is how former prime minister Tony Blair called her after her death.

I was later offered a lot of money to talk, especially by the Americans, but I never accepted

Sami Naïr

There was a fairy-tale wedding; then the relationship soured; then the couple’s dirty linen was aired in public; then came the separation and divorce...In the days before Twitter, Instagram and social media, the tabloids covered the story exhaustively, day after day, minute after minute, for all of 16 years – up until Diana’s tragic death, the Queen’s cold reaction, the mourning by millions of Britons, and the princess’s unofficial rise to sainthood status.

“She proved that the royal family, as an institution, was out of touch with the times,” recalls Denis MacShane, a Labor politician who was an MP for Rotherham at the time. “There was an outpouring of grief that I had never seen in England before: we are not an emotional people. It was like something out of the Middle Ages. Thousands and thousands of people were crying. I remember phoning the Queen’s private secretary and saying: ‘Look, if she doesn’t come down [Queen Elizabeth was on holiday at Balmoral Castle in Scotland] and if the royal flag is not at half-staff soon, within a week we’re going to have a republic.”

When he got a call about an accident inside a tunnel near the Seine, and was told that the celebrity in question might be the Princess of Wales, Sami Naïr had never yet seen a photograph of Diana. He had never been interested in royal affairs. He woke up Philippe Masoni, the police prefect in Paris, and 10 minutes later the latter called back with the confirmation: “It was Diana all right.”

Naïr then called the minister, who was not in Paris at the time. Diana was still alive at that point, trapped inside the Mercedes at the site of the crash. Dodi Fayed and the driver, Henri Paul, were dead. Diana and the bodyguard, Trevor Rees-Jones, clung to life.

Naïr went down to the hospital. It would still be 45 minutes before Diana was brought in. Naïr and Chevènement were waiting. The ambulance showed up between 1.30am and 1.45am. The driver and a nurse, together with Naïr and Chevènement, took her out of the back of the vehicle.

“Her face was angelical,” recalls Naïr in a telephone conversation. “She was very pale. Blonde.”

It was getting close to 2am and very few people knew about the accident yet. The British ambassador, Sir Michael Jay, who did not speak a word of French, was also at the hospital. Prime Minister Lionel Jospin was informed later. President Jacques Chirac could not be located that entire night or the next morning, a fact that spawned a vaudevillian subplot to the Diana tragedy. “We never did manage to get through to the head of state,” writes Aquilino Morelle, then an advisor to Jospin, in his book L’abdication. Some theories hold that he was spending the night with a woman outside the Elysée.

While doctors did what they could to save Diana’s life, Naïr and the others waited in a nearby room. At 4am, they were told that she was dead.

“The ambassador started to weep like a child,” says Naïr. “We called Jospin and he asked us to warn the Queen.”

Naïr got in touch with the Queen’s head of protocol. Tony Blair already knew. So did US President Bill Clinton, who had phoned Jospin even before Diana was dead.

It was now 4.30am. Dodi Fayed’s father had arrived, and Naïr was in charge of receiving him. “I saw a very tall, pale man, who carried himself in an extraordinary, noble manner. He said: ‘It is fate; God wanted it this way.’ He asked to see her. The minister acquiesced. He went in to see her. He placed a hand over her forehead.”

Naïr and Chevènement prepared the statement to the press – a piece of paper that he still keeps, as many other documents relevant to that night – and he remained inside the hospital until Prince Charles showed up.

By now, Diana’s death had ceased being a French matter. It was now a British issue, a global issue. In the following hours, the first displays of grief would begin in Britain. There was a week of catharsis that probably transformed the British monarchy forever.

“Diana’s death was a wake-up call for the monarchy: they had to be closer to the people,” says MacShane. “It was part of an extraordinary change in Britain that probably began with the rise to power of Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s. The Britain of Dunquerque, of Empire, of Winston Churchill, of conventional mores, in which gays were sent to prison – that Britain died very quickly. London became a more international city, more modern and gay. We switched from an industrial Britain to a financial Britain, with tremendous differences between rich and poor; a country committed to building Europe, and with a young prime minister from the Labor Party [Tony Blair] who practically incorporated the Diana myth into his own idea of the country.”

Diana and her death captured the zeitgeist. The reverse of the coin is the self-absorbed Britain of the Brexit era.

Sami Naïr, who just a few hours earlier had barely known who Diana was, quicky understood the implications of what had just happened. “I immediately realized its impact. My first reaction was to keep quiet: to avoid the journalists. I was later offered a lot of money to talk, especially by the Americans, but I never accepted it,” he says. “One day,” he adds with a smile,” I will write a book titled My night with Lady Diana.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.