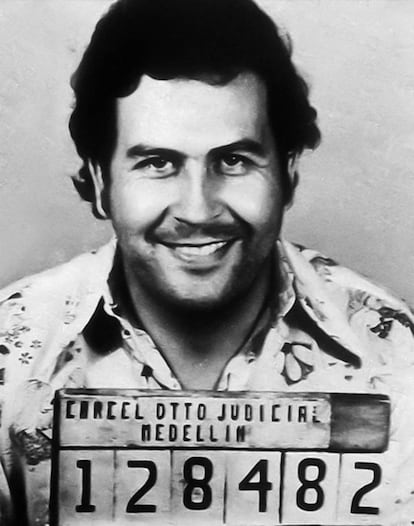

Pablo Escobar: a never-ending source of entertainment

The world’s most famous drug lord may be dead but his on-screen appeal is very much alive

With the release of the third season of Narcos on September 1, former Colombian cartel king Pablo Escobar is dead, leaving behind a legacy of corpses, mourning families and millions of dirty dollars. At the end of the second season, he was killed in a shootout in the city of Medellín, but no matter. After a life of excess and crime, Escobar survives as an obscure and enduring legend in the parallel universe that is the entertainment industry, inspiring a long list of authors, movie-makers and show-runners.

Aside from the third season of Narcos – produced by Netflix – this month also sees the release of Loving Pablo, the new movie by Fernando León de Aranoa starring Javier Bardem and Penelope Cruz.

Previously, we saw the controversial Colombian TV drama Escobar: the Boss of Evil, and the romantic thriller Escobar: Paradise Lost starring Benicio del Toro, along with several small-screen soaps and documentaries.

Even a figure of the stature of Nobel literature laureate Gabriel García Márquez could not resist tackling Colombia’s public enemy number one, in News of a Kidnapping, a non-fiction account of the abductions of a handful of prominent figures in Colombia in 1990. “In the 1990s, Gabo wanted to return to journalism and he wrote this book at the same time as the Foundation of New Iberoamerican Journalism (FNPI) was established,” says Jaime Abello Banfi, the foundation’s director.

When García Márquez wrote News of a Kidnapping, Escobar’s demise was too recent to turn him into a character in one of his novels. “That’s why he chose non-fiction. That, and because Escobar was the key to understanding Colombia at the time. It was a useful vehicle for resistance,” says Abello. “He lived it [the violence] first-hand. Not only was he very close to former Colombian president César Gaviria, who pitted the state against Escobar, but friends of his such as the publisher Guillermo Cano were killed by the drug cartels.”

News of a Kidnapping focuses on the capture of the well-connected Maruja Pachón de Villamizar, politician, journalist and sister-in-law of Luis Carlos Galán, another of Escobar’s high-profile victims. The book is based on the experiences of those who were abducted and offers insight into the cartel’s attempts to crush the system.

Escobar has also inspired Colombian authors Fernando Vallejo, Héctor Abad and Juan Gabriel Vásquez, and not forgetting his own son, Juan Pablo, whose Pablo Escobar, My Father, goes some way toward redeeming the man who was hated and loved in equal measure by Colombians. “When he was killed, I swore I would avenge his murder, a that promise lasted 10 minutes,” says Juan Pablo.

Instead, he has dedicated his life to making peace with the families of his father’s victims and asking for the right to a second chance, while distancing himself from his father’s criminal legacy.

He was keen to collaborate with the makers of Narcos, but was told it would be based on the accounts of Javier Peña, a Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agent at that time. He has since followed the series closely and, on first viewing, picked out 28 mistakes, which he posted on Facebook.

“This is very different from the reality,” he tells El País. “As far as I am concerned, I get smaller as the series goes on. Like Benjamin Button. They haven’t stuck to the truth in the series, but they aim to sell it to the world as though it were. I am also surprised at how much covering up of international corruption there is. Many of the agencies are a part of that corruption, feeding what is an excellent business for them and their citizens while the Latin Americans are left with violence with a capital V.”

The glorification of his life is having negative repercussions on younger generations

Juan Pablo Escobar, the drug lord's son

He believes his father would be amused by his glamorous on-screen persona. He does, however, respect Gabriel García Márquez’s News of a Kidnapping. “The glorification of his life is having negative repercussions on younger generations in Latin America who now believe that the drug world is cool,” he says.

Perhaps Juan Pablo Escobar would have preferred a series based on his mother María Victoria Henao’s memoirs. “She had to negotiate with the Colombian government and with the Cali cartel to get out of the country,” says Spanish producer Aitor Gabilondo, who was toying with the idea of serializing her story. “In the end, she was given a new identity and went to live in Argentina with her younger children. She lived anonymously until her accountant found out her true identity and began to blackmail her.”

The blackmail prompted Juan Pablo’s mother to tell her side of the story. “Her view is unique and that’s why we wanted to make a drama about it. But the project lost momentum, partly because so many series and films on the subject started to appear,” says the filmmaker, who is currently working on Vivir Sin Permiso (An Illegal Life) about a Spanish drug trafficker and modern-day King Lear.

Despite parking Henao’s story, Gabilondo recognizes that Escobar is a gold mine for the entertainment industry. “He’s the Maradona of crime; you’ve got an innovative, ostentatious, charismatic and very cruel drug trafficker,” he says. “He even got to dreaming of becoming the president of Colombia, and if it hadn’t been for his murderous instincts, he might have done so. He told his wife she should prepare herself to become the country’s first lady. He was the ultimate populist.”

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.