Nearly 600 prehistoric artifacts retrieved from trash container in northern Spain

Psychiatrist’s collection was inadvertently thrown out by widow, and nearly ended at a dump

If luck hadn’t seen someone find them first, nearly 600 prehistoric artifacts tossed into a waste container by mistake would have ended up at a city dump in northwestern Spain. Last January, a couple was walking down Rúa da Paz, near the fishing port of Vigo, in the region of Galicia, when they noticed something odd inside a waste container. Sticking out from the assorted debris were some carved stones that had labels with numbers on them.

The local police were called in, and by the end of the day the stones had ended up at the Quiñones de León Municipal Museum, where employees began the arduous task of recovering a collection that has been described as “large” and “of scientific interest.”

In Galicia, it is quite common for private individuals to make archeological findings on their land, and for families to donate them to a local museum once Grandpa – typically the one who found them – passes away.

Even so, “this case is unheard of, it is like nothing we had ever seen before, plus there’s a ton of objects,” says José Ballesta, the museum director. Ballesta underscored that the main thing is that this story has “a happy ending,” and that no culprits should be sought out.

During the investigation, the police discovered that the items had come from a storage unit being emptied out by construction workers on behalf of the widow of José Manuel García de la Villa, a psychiatrist who died in 2014.

De la Villa had harbored a passion for archeology since his days as a young man under the Franco regime, a time when there was still no strict regulation regarding what to do with archeological findings. The amateur archeologist had scientific training, and had been collecting stone and ceramic tools ever since he got his degree in psychiatry at Salamanca University.

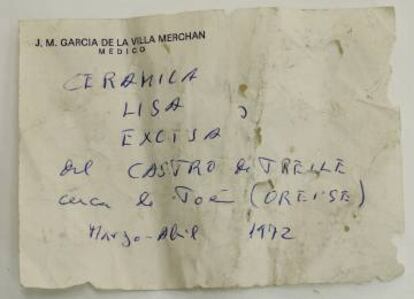

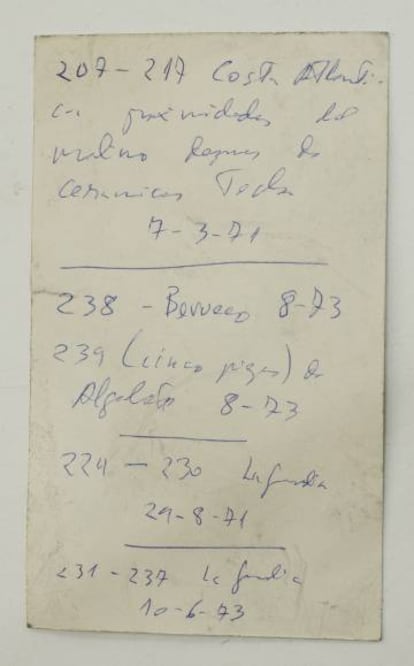

He carefully marked each item with a small white sticker and wrote a reference number on it. He also kept handwritten lists with all sorts of details regarding the origin of the pieces.

When the widow was contacted to clear up why these valuable items had been thrown out, “she was very upset,” says the museum director.

“She told us that she was very sorry, that she hadn’t paid attention to the things that were being thrown away, and that her husband would have never wanted that,” he recalls.

The widow “cooperated fully” and searched her home for the ledgers where García de la Villa had kept information about each item. All that emerged were “a few loose sheets” that helped a team of archeologists hired by the city of Vigo to put the vast collection in order.

Little by little, the artifacts were pulled out of the trash bags and deposited in 11 boxes. Experts found 594 pieces from the Paleolithic and Mesolithic eras, dating back to between 300,000 and 7,000 years BC.

Working with the loose sheets, with the stones themselves – some of which had a year and place of origin written on them – and considering the way they were carved and the doctor’s own biography, experts were able to determine where the ceramics and tools had come from.

They had been found at sites in Salamanca, in Toén (a municipality in the Galician province of Ourense) and on the banks of the River Miño. In fact, nearly half of the items (266) came from the mouth of this river in Pontevedra that flows between Galicia and Portugal. Before working in Vigo, the doctor had worked at a psychiatric hospital in Toén that has since shut down.

Even today, the sandy terrain at the mouth of the Miño, between the municipalities of Camposancos and Caminha, still yields an abundance of “picos camposanquienses,” a typical tool used as weights for fishing nets.

García de la Villa “was not a looter,” says the museum director. “We are talking about the early 1970s. Those were different times. And he knew what he was handling, and did so using protoscientific criteria.”

The collection, which also includes ceramic pieces ranging from prehistoric to Roman times, “is not particularly brilliant from an artistic point of view, but rather from a scientific one.”

The Vigo-based Quiñones de León Museum holds a large collection of stone axes and other tools typical of the cultures that once lived at the mouth of the Miño. Now, the museum director will consider “incorporating the new items” into the museum holdings, but thinks that it would be more appropriate to approach Salamanca institutions regarding the pieces that came from there.

Meanwhile, Ballesta is being contacted by people who inherited old artifacts from their older relatives and no longer wish to keep them at home. “We are currently in touch with a family from Argentina whose grandfather was originally from here,” he explains. When he emigrated to the Americas, he took with him all the prehistoric treasures that he had found while working his land.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.