Death notices are a husband’s yearly tribute to his deceased wife

Since 1995, José Luis Casaus has kept his spouse up-to-date with his news in EL PAÍS

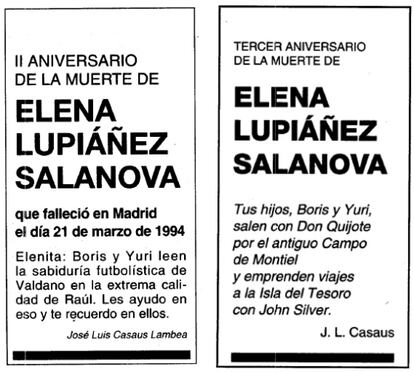

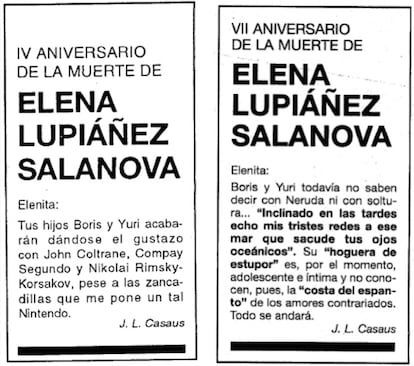

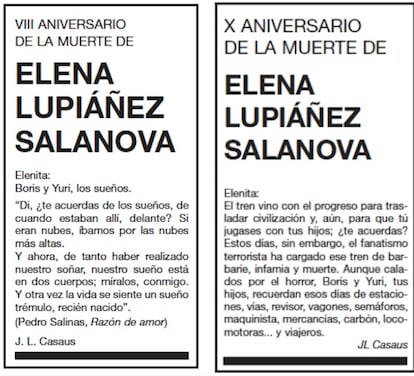

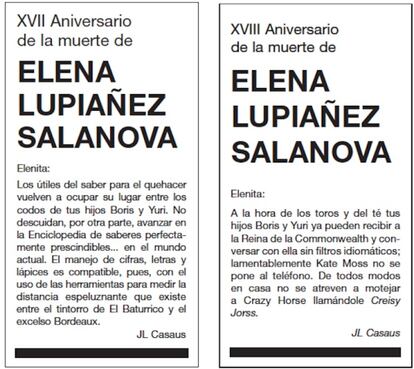

Every March 21 for 23 years, there’s an obituary notice in EL PAÍS signed by José Luis Casaus. It is a brief correspondence with his wife, Elena Lupiañez Salanova, on the anniversary of her death, an opportunity to talk about his life and the lives of their twins, Yuri and Boris, who were only six years old when she passed away in 1994 from lung cancer.

It has been his way to keep their love story alive. “We are not believers,” says Casaus. “And I am aware that it is a message to nothing but her memory, which does exist.”

Ojalá alguien me escriba esquelas así de bonitas 23 años después de mi muerte. (Hoy en @el_pais) pic.twitter.com/CcHrxDPBBf

— Latanace (la otra Celia Blanco) (@Latanace) March 21, 2017

I hope someone writes such beautiful death notices for me 23 years after my death.

His annual missives have garnered a following on the social networks. As the Zaragoza-born Casaus, 64, who now lives in Madrid, points out: “I was writing tweets before tweets were invented.”

Most years, he tells ‘Elenita’ about ‘Los Fulanos’ – the ‘so-and-sos’ – his affectionate term for their sons. This year, he says they have just flown the nest and that he is more or less broke. “They are independent but they’re still dependent on my wallet,” he tells EL PAÍS with a chuckle. This is a familiar situation for many families and the messages from Casaus provide an interesting snapshot of Spain’s recent history, including a reference to the 2004 Madrid train bombings in one (see 10th anniversary entry below).

The couple met in 1986. Elena was one of the founding employees of EL PAÍS, working in the advertising department, while José Luis was a spokesperson for the United Left Party. Scarcely a year later, identical twins Yuri and Boris were born. Casaus says they were given Russian names as they were conceived in St Petersberg, albeit when it was still called Leningrad.

My tradition of posting notes in the obituaries is my way of trying to lighten the tragedy José Luis Casaus

The twins, who are about to turn 30, hardly remember their mother. “In the last period of her illness they didn’t have much contact because she didn’t want them to see her like that, them being so small,” says Casaus.

“That someone should die so young is heart rending, but my tradition of posting notes in the obituaries is my way of trying to lighten the tragedy. That’s why there’s a touch of humor to them.”

Casaus makes sure to consult his sons before he publishes as they often contain private details about their lives. Looking back through the years, there are references to their travels, their cellphone addiction and their status as so-called mileuristas – a Spanish term for people who earn no more than €1,000 a month.

Both brothers studied business and now work sporadically – “when they can, on short contracts,” explains Casaus, who adds that right now, they are both in work.

Besides bringing ‘Elenita’ up to date on news of the family and friends, Casaus quotes writers and singer-songwriters to illustrate his theme. In this year’s note, he includes a few lines from a song in the milonga style by Uruguayan poet Alfredo Zitarrosa in reference to his sons leaving home. “I can teach you how to fly, but I can’t follow your flight.”

Others have included lines by the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda or Argentinian writer Jorge Borges. “They are almost always people that we both liked,” says Casaus, adding that perhaps the time has come to end his annual tribute to his wife’s memory.

Here is a small sample of the notes from Casaus rescued from the EL PAÍS archives, with a translation underneath.

English version by Heather Galloway.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.