Madrid region approves new dignified death measures

Palliative care will be provided at hospital or at home, but physician-assisted suicide is not an option

The Madrid regional assembly on Thursday unanimously approved the final draft of a law regulating palliative care in the last stages of life. The new legislation stipulates that terminally ill and agonizing individuals may receive comprehensive palliative care in a hospital (either public or private), or in their own home, if they so wish. The law also sets out the duties of health professionals and provides for their legal security.

Madrid thus becomes the ninth Spanish region to pass this kind of legislation, following the example of Andalusia in 2010. The others are Galicia, Asturias, Catalonia, Basque Country, Navarre, the Balearic Islands and the Canary Islands.

However, none of these laws contemplates either euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.

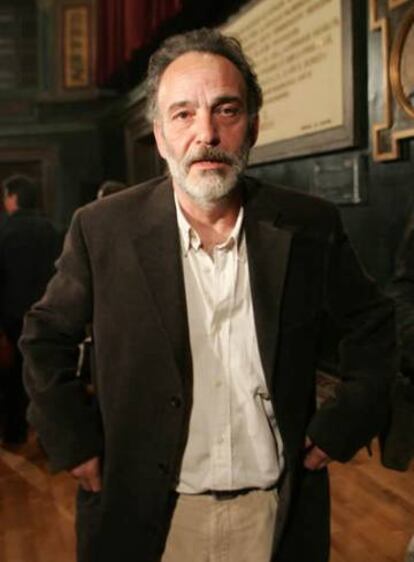

These laws have not improved quality of life; only a voluntary death law will do that

Luis Montes, Right to Death With Dignity

The Madrid bill was first introduced in July by the Socialist Party (PSOE), and provides a legal framework for patients and health professionals alike. The former may reject treatment, palliative sedation and life support if they so wish. Patients will also have to be constantly appraised of the situation, so they can freely make informed decisions.

Palliative care is cross-disciplinary, extending not just to the patients but also to their families and other relevant individuals. The goal is to keep pain and other symptoms under control in people who are not responding to curative treatment, in order to “preserve the best possible quality of life until the end.”

José Manuel Freire, a Socialist assembly member and spokesman for health issues, said that this new law means “all citizens will have the right to receive this kind of care. According to existing figures, in 2014 this kind of care was only reaching 20% of individuals in need of it,” he added.

The law includes the right to leave instructions at relevant agencies in the event that patients should lose the ability to personally express their wishes following an accident or disease. This possibility already existed, but forms could only be filled out at a single office on Sagasta street. The Madrid Health Department will now create new offices where people may indicate their wishes, and this information will have to be added to a patient’s medical history.

A real death with dignity

But Luis Montes, president of the association Derecho a Morir Dignamente (Right to Death with Dignity), is asking for “a voluntary death law that liberalizes the whole death period.”

There are two pieces of national legislation covering “the process of death,” said Montes, who is himself a doctor. The Penal Code makes euthanasia and physician-assisted death a crime. The 2002 Patient Autonomy Law recognizes a patient’s right to refuse treatment.

Regional laws like the one just passed in Madrid do not allow patients to die when they desire, explains Montes. Instead, they stipulate that health professionals must inform patients about their options, that patients may leave early instructions regarding whether they wish to die in hospital or at home, and who should be with them at the moment of death. The laws also guarantee the right to palliative care.

But ultimately, “these laws have not improved quality of life; only a voluntary death law will do that,” said Montes.

In January, the leftist Unidos Podemos group introduced a proposal in Congress asking for voluntary death to be decriminalized. Such a move would bring Spain closer to Belgium or The Netherlands.

English version by Susana Urra.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.