The wronged man: The case of Romano van der Dussen

EL PAÍS talks to the Dutchman who spent 12 years in jail for rape until DNA proof showed his innocence

When Romano van der Dussen was finally released from a jail in Palma de Mallorca on February 11 after spending 12 years behind bars for a crime he did not commit, he was greeted by a horde of reporters eager to hear his story. Few there that day noticed a woman standing patiently to one side, waiting until the 42-year-old Dutchman had finished talking to the journalists.

“She is the only good thing to happen to me in the last 12 years, perhaps in my whole life,” he says wistfully.

The woman, who wishes to remain anonymous, had seen a headline in EL PAÍS in September 2014 that read: “Man condemned for rape remains in prison seven years after DNA evidence exonerates him.” As a result, she contacted Van der Dussen, and the two began writing to each other. “She appeared in the midst of this hell. Not even the nurses in the prison hospital would touch me, because I was a rapist. Then this good woman started to believe in my innocence and spoke kindly to me. I started to feel like a person again and that I could regain my dignity and rejoin society,” he remembers.

“How do you get over being treated like trash for so many years? On my first day in jail I was beaten up so badly I spent the next three weeks in the hospital wing. The guards knew they couldn’t guarantee my safety, so I had to be put in solitary. For 18 months I was alone for 23 hours a day, going crazy, living through a nightmare.” He spent the rest of his sentence being transferred from one prison to another, spending his time in secure units for child molesters and rapists.

While locked up, Van der Dussen has become an uncle, but has never met his nephews. His mother also died while he was behind bars

For the moment, he is staying in a Church-run halfway house in Palma de Mallorca, and still has no idea about what to do with the rest of his life. The Dutch government has offered financial assistance and psychotherapy, along with an apartment in Kerkrade, a pretty town close to the German border. Van der Dussen knows that the sensible thing to do would be to accept and leave Spain behind him. He has no money, and says he is not yet strong enough to work. It will be months before he can claim compensation for his wrongful imprisonment, and there is still the matter of his exoneration for the other two rape charges he remains guilty of in the eyes of the Spanish legal system. That could take many more years, and may never happen.

September 2, 2003: From heaven to hell

That morning, like so many others that first summer on Spain’s Costa del Sol, Van der Dussen had been to the beach. He was jobless after the ice-cream parlor in Fuengirola where he had worked earlier in the summer had closed, but was confident an interview with a resort complex in Marbella would yield work thanks to the four languages he speaks. In short, he was a 30-year-old without a care in the world.

Returning to his apartment around midday, he was stopped by two police officers. They asked his name and told him that he was under arrest.

He was held for two days and then transferred to prison to await trial. His 12-year-long nightmare had begun.

Van der Dussen soon learned he stood accused of the rape of three women during the night of August 2003, a month earlier. The women had been brutally beaten; one of them so badly that she could remember nothing about what had happened to her and was in a state of shock.

The attacks had taken place soon after the murder of two young women in nearby Coín and Mijas, and the police were under pressure to put somebody behind bars.

While Van der Dussen awaited trial in jail he wrote to the magistrate overseeing the case, saying he had an alibi and could provide witnesses who would testify on his behalf. At this point he was still confident he would be released, sure that there was no DNA evidence linking him to the crimes.

May 25, 2005: “I hope they send you to hell”

But things started to look bad even before the trial began. His lawyer, Celia Martín Aurioles, told him that the public prosecutor’s office had offered a deal: seven years in jail if he confessed. With 18 months of his time already served while awaiting trial he would soon be transferred to a Dutch prison and would be eligible for parole. But Van der Dussen refused, still believing that the Spanish justice system would see he was innocent. Two of the rape victims were in court on the first day, hidden by a screen, and they identified him. “I hope they send you to hell,” said one of the women. Another fainted when she saw him. The two victims who gave testimony in court appeared absolutely certain that Van der Dussen was the man who had savagely beaten and raped them.

The next day, the expert witnesses gave their testimony: the DNA found on one of the victims, along with fingerprints, did not belong to Van der Dussen. None of the security cameras in the area where the attacks took place contained any footage of him. The only evidence presented in court was the testimony of two of the victims and that of a witness who claimed to have seen Van der Dussen from the balcony of her apartment close to where the attacks took place. And so, on May 25, 2005, he was found guilty by the three magistrates deciding the case in Málaga’s High Court – José María Muñoz, Lourdes García, and María Jesús Alarcón – who sentenced him to 15 years and six months in jail for sexual assault, aggravated injury, and robbery with violence, emphasizing the identical modus operandi of the three attacks.

It is worth noting that the verdict makes no mention of the DNA found on the pubis of one of the victims that did not match Van der Dussen’s. One explanation would have been that it belonged to a boyfriend, but she said she had not had sex with anybody else that evening or in the previous days. Seemingly, it did not occur to the three judges that somebody else might have raped her.

Furthermore, the prosecution said that Van de Dussen had not provided any witnesses to support his alibi, which was that he was with friends at a party in Torremolinos on the night of the attacks. In fact there were several letters in the court’s possession written by the Dutchman mentioning several people by name who could vouch for him and providing their contact details. Van der Dussen’s lawyers presented written testimonies and asked for the witnesses to be called. The three judges refused.

“Two weeks after the hearing, the lawyer called me to say that I had been found guilty,” says Van der Dussen, still visibly affected by the experience. “It was a huge shock, one of the toughest moments of it all. I tried to slash my wrists with the lid of a tuna can,” he adds, showing the scars on his wrists. “I just couldn't deal with it, and of course that’s what they all wanted. They would say that I couldn't deal with what I had done and that’s why I had taken my life. It would be just another piece of evidence against me. So, on that day I decided I would fight to the end to get justice.”

But the Supreme Court turned down Van der Dussen’s appeal, and by the time he tried to bring the case before Spain’s Constitutional Court, the deadline had passed; and as all the options within the Spanish legal system had not officially been exhausted, the European Court of Human Rights could not take up the case. Everything that could go wrong was going wrong.

A difficult life

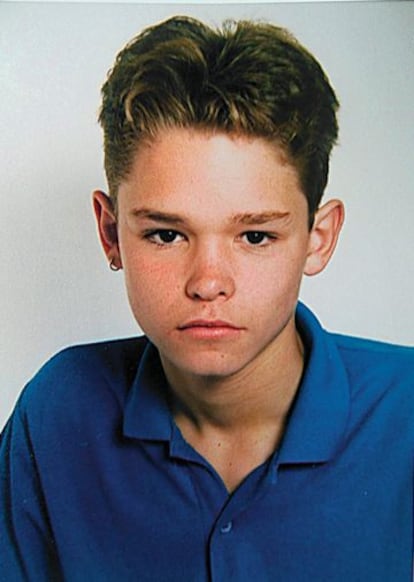

Van der Dussen’s life has never been easy. His father ran a small insurance company and his mother was a housewife. She had been raped before Van der Dussen was born and become pregnant, eventually deciding to keep the baby. This was Van der Dussen’s elder sister, who while in her teens became addicted to drugs and worked as a prostitute to pay for her habit. At the age of 14, in the face of the worsening situation at home caused by his sister’s problems, Van der Dussen was put into the care of the local authority. He soon got into trouble and became addicted to drugs. Eventually, after kicking his drug habit, he moved to Spain in the hope of starting a new life with his then girlfriend. They had a baby, but separated soon after she was born. The girl was aged two when he was sent to prison.

While locked up, Van der Dussen has become an uncle, but has never met his nephews. His mother also died while he was behind bars. The case has even split the family: his younger sister, who is a police officer, refused to believe his innocence, arguing that in Europe it was impossible for somebody to be locked up for a crime they did not commit.

May 10, 2010: A British psychopath

Five years into his sentence, a Dutch diplomat visited Van der Dussen in jail to tell him that the DNA found on one of the rape victims had turned out to be that of Mark Dixie, a British national in jail for murder and rape who had been living in Málaga at the time of the offenses Van der Dussen was now serving time for having committed. The Spanish police had known about Dixie since 2007. The year before he had been arrested and his genetic profile entered into the Veritas EU database, which made the connection with the DNA found in Fuengirola three years earlier.

The Spanish police eventually requested more information about Dixie’s genetic profile, but the British authorities never responded, saying the paperwork had not been presented properly. The first that Van der Dussen heard about this development was from the Dutch diplomat who visited him in 2010. He then contacted Madrid-based attorney Silverio García Sierra, a public lawyer who had handled one of Van der Dussen’s many appeals. García Sierra worked pro-bono on the case for the next five years, playing a key role in securing his release.

But a case that should have taken a matter of months to clear up was instead delayed again and again by red tape. “It’s as though the case was somehow cursed,” says García Sierra. “Everything has been done badly, the whole thing has been a disaster. When you look through the indictment, you can’t believe the mix of irregularities, shortcomings in the investigation, and sheer bad luck: it’s one act of negligence after another. Those final years were ridiculous. Nobody seemed in any hurry to establish whether an innocent man had been sent to jail: either in the United Kingdom or in the Spanish courts. The whole thing was exasperatingly slow. Just when it looked like he was about to be released and he got his hopes up, some new piece of paperwork would appear that had to be filled in.”

It’s important to remember that of the three rapes Van de Dussen was convicted of committing, he has only been acquitted of one. The Supreme Court has refused to look into the other two convictions, despite his sentence being based on the three judges’ decision that the crimes were all committed by the same person. Van der Dussen’s lawyer has lodged a new appeal based on further evidence, along with the testimonies of the witnesses who were with the Dutchman on the night the rapes took place. What’s more, a properly conducted police investigation would have found further DNA or fingerprints on the clothes and bags of the other two victims, which the authorities did not bother to analyze or even keep.

Not an isolated case

How does somebody who is innocent of any crime end up in jail? Cases such as that of Ahmed Tommouhi, Rafael Ricardi and José Antonio Valdivieso – to name but a few of those who languished in jail for crimes they did not commit – suggest that Romano van der Dussen’s is far from the exception and that the Spanish authorities repeatedly mishandle investigations, jump to conclusions, and that in their haste to close cases, cut corners by not properly following procedures.

Van der Dussen had been detained by the Spanish police on three occasions prior to his being accused of the rape of three women in 2003: for damage to public property and after two complaints filed by his former partner. None of the cases led to prosecution; nevertheless, he remained on the police’s database. His conviction seems based solely on the evidence of two of the rape victims, who swore under oath that he was their attacker. But a closer look at the indictment shows that the three women gave evidence to the police either on the night of the attacks, or the next day. Their descriptions of the rapist differed: he was blond; he was brown-haired; his hair was long and it was short; his shirt was light colored; it was dark. The only thing the three agreed on was that their attacker had curly hair. The first time they were shown photographs of possible suspects, including one of Van der Dussen, they did not pick him out. A few days later, one of the victims was able to identify him “without a shadow of a doubt,” but another was uncertain and later failed to pick him out at an identity parade.

“Victims and witnesses sometimes get it wrong,” says Margarita Diges, professor of psychology of memory at Madrid’s Autónoma University. “And the reason is often because of the police’s mishandling of an investigation. If witnesses are led to believe they have correctly identified a suspect, or if they are shown a single photograph of somebody when making their statement, later on they will almost certainly identify that person, insisting that they are sure. It’s called false memory. The problem isn’t so much that this produces mistaken identities, but that these statements are accepted in court as evidence and given precedence over DNA. The empirical data shows that identification is wrong about half the time.”

Looking back on his tragic story, Van der Dussen says he feels sorry for the women who testified against him in court. “It was obvious they had suffered greatly. But it wasn't me. If the police investigation had been carried out properly, I wouldn't have spent 12 years in jail, and could have kissed my mother before she died and seen my daughter grow up. None of this should have happened.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.