How a Mexican cowboy laid down a challenge for Hitler and the Nazis

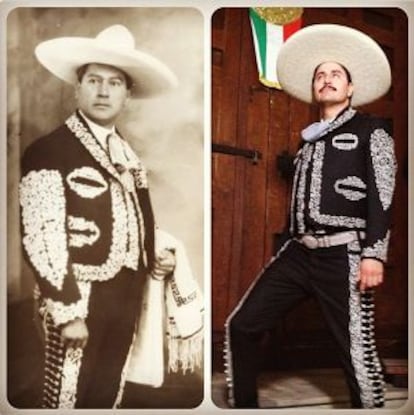

Filmmaker puts the fascinating story of his grandfather, Antolín Jiménez, on screen

In 1942, two months after Mexico formally declared war on Adolf Hitler and his Axis allies, Antolín Jiménez took it upon himself to organize a force of traditional Mexican cowboys – known as charros – to defend his country in case of an – albeit highly unlikely – Nazi invasion.

This army soon came to prominence throughout Mexico and became heroic symbols of the country’s patriotic values.

Jiménez, a Tabasco state native, trained and organized thousands of men, who soon formed about 250 contingents throughout the country. They called themselves the Legion of Mexican Guerrillas.

Despite its somewhat surreal tone, this story actually happened, and is a fine example of how the truth can often be more fascinating than fiction.

As I got older, I asked myself why his name was rarely brought up at home”

Over the years, documentary filmmaker Fernando Llanos has been collecting news clippings, photographs, pamphlets and other materials that detail the lives and exploits of this charro force.

The 41-year-old Mexico City native has put together a documentary called Matria, which was presented on Thursday at the “22 x Don Luis” Film Festival in Calanda, Teruel province, the birthplace of legendary Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel.

This is the first time that Llanos, who is also an artist and performer, has produced a long feature documentary, the subject of which focuses on the life story of Antonlín Jiménez.

Besides being a politician, publisher, mason and president of the National Association of Charros – one of the most important and prestigious Mexican cultural organizations – Jiménez was also Llanos’s grandfather.

“Antolín Jiménez took part in major events in his time – it was Mexico’s golden era,” explains Llanos, who adds that his family was opposed to the project, especially his mother, who is the youngest of Jiménez’s seven children.

“He fought alongside Pancho Villa, and President Lázaro Cárdenas admired him so much that he gave him a horse. But for many years to me he was just my grandfather, who died nine months after I was born.

“As I got older, I began to ask myself why his name was rarely brought up at home, why did it seem that everything he did was stunning but at same time cold and mysterious,” Llano recalls.

He began to trace back his grandfather’s story through family documents and by tapping into the memories of those who knew him. That’s how he found out that Jiménez’s life had been entwined with some of the most important political and social events that took place in Mexico in the 20th century.

“It is a fascinating story but at the same time it shows how building a political system of excesses has greatly cost the Mexican people,” he says.

Matria – a reference to the famous charro motto Todo por la patria (everything for the homeland) – won the Best Feature Documentary prize at Mexico’s prestigious Morelia Film Festival last year.

Funded by public grants, the documentary begins with a young Jiménez, a soldier in Pancho Villa’s rebel army, blowing up trains with dynamite in Chihuahua. He goes on to participate in the Mexican Revolution, including Villa’s victory in Torreón in 1914 and later defeats in Celaya and Agua Prieta.

“After his revolutionary feats, he went on to Mexico City in search of money and love, but soon entered the world of politics. He served as a deputy for three terms and for three different parties, including representing a state where he wasn’t even born.

My family was always stigmatized by the fact that we were the offspring of one of his lovers”

“He shared the views of President Álvaro Obregón [1920-1924] and went on to help form a party [Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI] that would remain in power for more than 70 years,” Llanos explains.

In Matria, Llanos narrates how in 1920 his grandfather joined the masons, as did other Mexican historical figures, such as former Presidents Benito Juárez and Lázaro Cárdenas.

He also opened a tax office and later converted it into a publishing company, where he worked his entire life.

“After the latidunfios [private land ownerships] were broken up, many charros moved to the big cities and became performers in rodeos and other public events. In the 1950s, Mexico idolized the charros in film and literature as the country’s most important cultural symbols,” Llanos says.

“Antolín already had money, social status, political power and national recognition. So he saw a way of capitalizing on charro culture and demonstrating the values held by these men on horseback. That’s how the army came to be.”

The videographer doesn’t try to hold back on discussing his family’s skeletons-in-the-closet, including the scandalous gossip that Jiménez had his first wife killed.

“To be truthful, he had two families for many years. My family was always stigmatized by the fact that we were the offspring of one of his lovers. I don’t think that his first wife died in a car accident that was planned, in the same way I don’t believe that her family put some black magic hex on mine,” he says.

English version by Martin Delfín.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.