The dying days of the phone booth

Spain has been removing call boxes for the last decade, and the last will go as of 2017

Once again, Winnie the Pooh is mad at Pocoyo, and there’s been a bit of pushing and shoving. Although at least today they haven’t come to blows, as they and the other life-size cartoon characters often do over which area of the Puerta del Sol they can try to persuade parents to part with a couple of euros to have their children’s photo taken with them. The relative peace may have something to do with the absence of Hello Kitty, who two Romanian prostitutes say is the most aggressive in defending her turf. Meanwhile, a tearful Minnie Mouse, sweating inside a felt suit while the temperature outside is pushing 40°C, is being consoled by Mickey after a pedestrian pushed her out of the way. This all may seem somewhat strange, but the really odd thing about this underworld in the very center of Madrid is that yesterday, three people used one of the 12 public telephones here – specifically, 7313U. The phones, vandalized and underused, are due to be removed from December 2016 onward, unless the government changes its mind.

The really odd thing about the underworld here in the very center of Madrid is that yesterday, three people used one of the 12 public telephones

There are 25,820 public phones left in Spain, a quarter of the number in 2000. In the last three years alone, 40 percent have disappeared. None of them cover their maintenance costs. And the Puerta del Sol is perhaps the place with the largest number of these 20th-century artifacts, which have now been overtaken by smartphones and international calling centers. Number 7313U is battered, but still hosts advertisements that bring in €20 a day.

Located close to the confluence of two of Madrid’s busiest pedestrian streets, Preciados and Carmen, over the course of 10 hours, just three people tried to make a call from it: a Bolivian who had just arrived in Madrid and needed to contact a friend; a Spanish woman who had left her phone at home and wanted to talk to her boyfriend, and a self-described romantic with a call card: “If you can do anything, help stop them being removed,” he says.

In some countries, like Belgium, there are no public phone booths, but for the moment, here in Spain, in the absence of callers, they also have other uses.

Juan José Coronado, a 67-year-old Madrid native, and his friend Jaime Solano, a 65-year-old Ecuadoran, take shelter from the sun in the booth. Coronado is dressed as Bart Simpson (the suit cost €200 and came from Peru), and Solano is the second Pocoyo (not the one that was fighting with Winnie: it turns out there are four Pocoyos in the Puerta del Sol). Jaime says he is something like Juan José’s secretary, and helps him inflate the balloons he tries to sell (he only has one arm). “Nobody uses the booths, they just swallow coins; they don’t work. I use it for shelter,” says Juan José as Jaime nods in agreement.

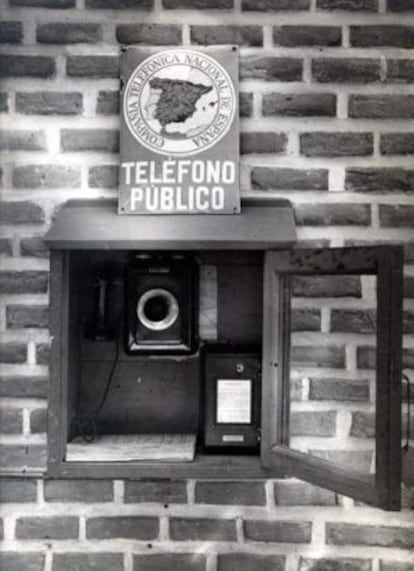

The first public phones were installed in Madrid in 1928 in a bar in the Retiro park, and required tokens. But it wasn’t until 1966 that the government of Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco began installing coin-operated booths in the streets.

In some countries, like Belgium, there are no public phone booths, but for the moment, here in Spain, in the absence of callers, they also have other uses

Juan José is right about 7313U swallowing coins, and most days manages to hook a few out using a piece of wire. But today the phone is dry. He says that he has extracted two euros from another close by, and ten cents from another. “This one is crap. Everybody tries to get money out of it but they never find anything,” he says. The phones are also regularly vandalized, which makes them an even bigger cost for Telefónica, the privatized former state monopoly responsible for the country’s network of public telephones. For the last 13 years, Telefónica has been left with a similar feeling to Jaime when 7313U swallows his money but doesn’t connect his call. But for the moment, Telefónica is obliged to maintain a reduced network until the end of 2016, based on one telephone per 3,000 people in large and medium-sized communities, with at least one in villages of less than 1,000 inhabitants. That adds up to around 30,000 phones in a country with 50 million cellphones, more than one per person.

It wasn’t until 1966 that the government of Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco began installing coin-operated booths in the streets

Which is why, although he could spend the afternoon and evening leaning against 7313U, Nicola, a Romanian rent boy who charges €50 for “encounters” with older men – although he insists he prefers women – never takes the phone off the hook. He has a smartphone, as does Rey, one of the many sandwich-board men who advertise for pawnbrokers in and around the square. “I only use my cellphone,” he says. Or Diego Porcel, who has been selling lottery tickets here for the ONCE blind charity for the last 13 years and who has bought himself a smartwatch he can make calls from. “It’s a whim, but the booths? Hardly anybody uses them. You just see people hitting them,” he says. Nobody, not even those who put in 10-hour working days as Bart Simpson, can remember the last time a call was made from one of these phones.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.