A half-century of life through a Latin American lens

‘Latin Fire’ show is centerpiece of this year’s PhotoEspaña photography festival in Madrid

A mass of heads belonging to members of the Argentinean military – with their caps, mustaches and stern expressions as they celebrate Army Day during the 1970s military dictatorship – welcomes you to Latin Fire. Other Photographs of a Continent 1958-2010, the exhibition at the center of this year’s PhotoEspaña photography festival, which is dedicated to Latin America.

The display of around 180 photographs on loan from the Anna Gamazo de Abelló Collection can be seen until September 13 at Madrid’s CentroCentro exhibition space, situated in what was once the main post office and is now home to City Hall.

The images belong to what is probably the most important private collection of Latin American photography in Europe

Anybody imagining that this mosaic of images covering a half-century of life in the region represents some kind of thesis should think again, says PhotoEspaña director María García Yelo: “This collection of Latin American photography, probably the most important in private hands in Europe, has no common identity.” The works are from Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Brazil, Cuba, Argentina and Chile, but “there is no encyclopedic intention,” even though “this is the first time” that so many pieces from the collection have been shown together.

That said, looking at the exhibition, which took a year of negotiations and preparations to organize, there is a predominance of “reality, of the injustices experienced by Latin Americans,” says Colombian María Wills, who co-curated the show alongside Frenchman Alexis Fabry. Among the few common features that bind the works together are the mix of the popular and the urban, and the economic difficulties of the photographers, she notes.

The curators also explain that the English title, Latin Fire, which they took from a poster they saw for a salsa group, is a reference to the passionate character of Latin Americans, and also reflects the “overwhelming influence of the United States,” of its language and customs, on the culture of all its southern neighbors. “Although now the opposite is starting to happen,” Fabry points out.

The first part of the exhibition, dubbed Fire, features a collection of harsh images – of dictatorship, the disappeared, guerrilla fighters, street protests. “It is striking that the older photographers dealt with violence in its most explicit form, while the younger ones have preferred to bypass it, not to show it so obviously: they do not show murder, but instead the gun in the hand,” says Fabry. This is the case with the heart-wrenching images in Mexican photographer Maya Goded’s 2005 series Desaparecidas (Disappeared), which centers on the families of people murdered in the border city of Ciudad Juárez.

Latin nightlife

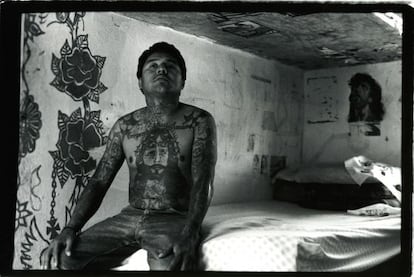

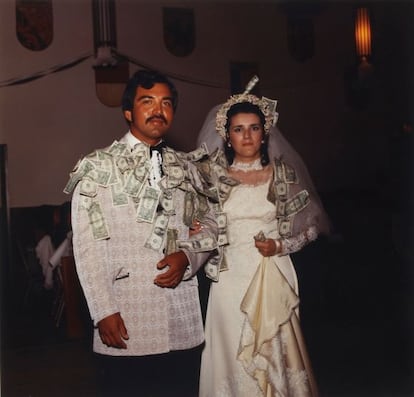

The second part, Con el diablo en el cuerpo (With the devil in the body) – the title of a song by Cuban singer La Lupe – is “a reflection of the craziness of the nightlife in cities such as Lima, Mexico and Buenos Aires,” says Wills. Alongside the images of bars and cantinas, there is a collection showing transvestites from Santiago de Chile, and another depicting, in black-and-white, the squalid rooms used by prostitutes, shot by Colombian Fernell Franco. Light relief comes in the form of Mexican José Luis Venegas’s series depicting high society weddings in Tijuana. Venegas is the father of singer Julieta Venegas and photographer Yvonne Venegas, whose work is also included in the exhibition.

Toward the end of this tour through late 20th-century Latin American photography are several black-and-white portraits that are hard to look at for long. One is El niño y el infierno (The child and hell) by Mexican Yolanda Andrade, which shows a young boy standing threateningly in front of a wall covered in graffiti. The other is El guerrillero herido (The wounded guerrilla) by Pedro Meyer. In it, a young Nicaraguan man whose legs have been partially amputated sits up on a hospital bed to show the scars of other wounds.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.