Handing the homeless a house

A pilot program providing apartments to those on the streets is proving a success

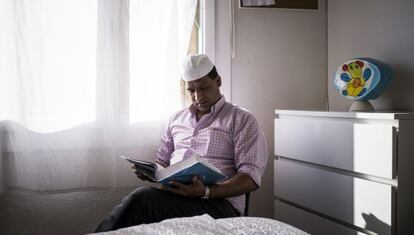

The only thing hanging on the walls of Ansir Hussain’s room is a bulletin board containing reminders of his next doctor’s appointments and a sketch of him drawn by a friend.

The 34-year-old Pakistani, who lived homeless on the streets of Barcelona for more than four years, looks reserved in the image. But when he offers a cup of coffee to visitors, Hussain perks up and becomes talkative.

“He has changed a lot,” says the coordinator of the program that has allowed him to find a home.

The program is based on the Housing First initiative created in 1992 in New York by Pathways to Housing

Ansir is one of 28 homeless people participating in a pilot program sponsored by the RAIS Foundation in Madrid, Barcelona and Málaga with help from the local city governments.

It is based on the Housing First initiative that was created in 1992 in New York by Pathways to Housing. But this program takes a different approach in helping people find housing.

Traditionally, the process starts with social services making contact with the homeless in order to get them into temporary homes and shelters. As long as they meet the required objectives, they will then be moved into hostels or shared apartments with other homeless people for a time. The ultimate aim is for them to get a place of their own.

But in Housing First, that chain is reversed. Under the traditional social services model, a relapse could mean sending someone back to the streets, creating a vicious circle that becomes difficult to break.

Alejandro López, deputy technical director for RAIS, explains that it was up to Ansir and the other program participants to decide whether they wanted to join, though they first had to be screened. Each candidate had to have been living on the street for at least three years and be free of any drug or mental health problems.

“When they made me the offer, I couldn’t believe it – an entire apartment to myself!” Ansir says.

The program started on January 2 with 10 apartments in Barcelona and a few others in Madrid. In Málaga, there are eight apartments. All of them are located in regular residential buildings with nothing special about the neighbors or the structures.

The only condition placed on participants is that the coordinator of the program must be allowed to enter the home once a week. Once participants start working, they also have to pay 30 percent of their wages.

They are not asked to stop using drugs or drinking alcohol or submit to any kind of medical treatment. These are decisions they will make on their own as their lifestyles progress.

“I take a shower, wash dishes and clean my home. I do have daily activities: I go see the doctor, I attend Alcoholics Anonymous sessions, and go to the market,” Ansir explains.

He is definitely a changed man from the old Ansir who used to drink and, frustrated because he couldn’t find work, refused to go to a Barcelona shelter because he was ashamed about ending up on the streets.

“The results have been positive over these past few months. All of the first participants are still in their homes,” says López.

At the same time, eight out of 10 participants have reduced their consumption of drink and drugs and reestablished contact with their families – some of whom they hadn’t seen in years. Half of them also know their neighbors, which is a sign they are strengthening their social links.

They are not asked to stop using drugs or drinking alcohol or submit to any kind of medical treatment

With these results, the Madrid and Barcelona governments have decided to give more support to this innovative model. Barcelona hopes to have 50 more homes by this summer.

“This is the future, even though we can never say that we won’t build more shelters,” said Maite Fandos of the CiU Catalan nationalist bloc and Barcelona’s fifth deputy mayor.

In Madrid, there are plans to make 10 more apartments available by the end of the year.

The Housing First method has also gotten good results in countries such as France, Canada, Portugal and Finland in recent years. While the model does not put a limit on how long a person can remain in the home, in Barcelona the maximum stay is three years.

Ansir knows the program has taken him off the streets and possibly saved him from drinking himself to death.

His home now smells of cleaning products – a symbol of how he has also cleaned up his own life. Now he hopes to get better, legalize his residency in Spain, and find work.

“What happened in the past was the past. My future will be better,” he says.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.