Cuban photography laid bare

A new book documents how the island’s photographers have depicted the human form

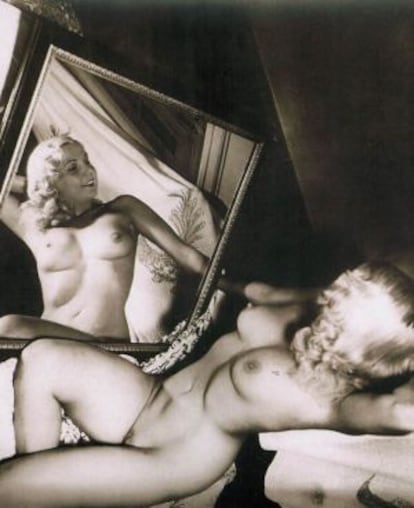

There are dancers in transparent veils, well-developed male torsos, voluptuous breasts, young tattooed skins, and a varied collection of pubises, penises and bottoms. The compositions run the gamut from surrealistic to provocative.

It all has a place in La seducción de la mirada (or, The seduction of the gaze), a book about the evolution of Cuban photography’s approach to the human body from the mid-19th century to 2013.

The author, Cuban poet and essayist Rafael Acosta de Arriba, has brought together over 400 images captured by 93 artists throughout the decades.

“This project began five years ago as a study of human eroticism,” says Acosta. “But it is not a book about nudes.”

The first, postcard-size images date back to the early 20th century. “They were made by companies that sold cigars, and were included inside the cigar boxes to encourage sales. At first they showed pictures of prostitutes.”

Acosta explains that photography arrived on the Caribbean island in 1840, not long after its invention. Several photographers specializing in portraits soon set themselves up in Havana, and began working under a clear Spanish influence. Later, photography would reflect trends more popular in the United States.

The recent thaw between Havana and Washington could be stimulating for Cuban art photographers

The first “nude cards” began circulating in 1880 among Havanan high society. By the early 20th century, journalism had already developed the concept of the photo essay, although it was not until 1927 that the magazines Carteles and Capitolio finally published a collection of female nudes by photographers from various countries.

“The first relevant name in human body photography in Cuba is Joaquín Blez,” says Acosta. An exhibition of his work in 1927 brought him fame, and Blez went on to become the official photographer for the family of President Mario García Menocal, and also founded the famous Club Fotográfico de La Habana, which attracted members from the middle and upper classes (“the bourgeoisie who practiced photography as a hobby.”)

To Acosta, the most talented member of that club was Roberto Rodríguez Decall (1915-1995), “because of his subtly erotic images, whose delicate nature overcame the hieratic attitude of his predecessors.”

Acosta explains that before the Communist revolution of 1959, it was unusual to see images of Cubans’ bodies. “They only showed up in a few magazines, and were always meant for private consumption. It was rare indeed to see them in public exhibitions.”

When Fidel Castro came to power, “there was a hiatus in this type of photography; there was no room for it because images were subordinated to political goals.”

Years would elapse before the human body again became a focus of Cuban photography. Yet it was around this time that a very famous picture was taken: La vida y la muerte (or, Life and death), also known as “Korda’s militiawoman.” It was “a very daring image” of a mixed-race woman whose face is not shown, naked from the waist up and wearing a militiaman’s fatigues, with a machine-gun resting “between her splendid breasts.”

The original photograph was lost, although the Cuban writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante said he was once given a copy by its author, Alberto Díaz, aka “Korda.” World famous for his iconic portrait of Che Guevara, Korda got into trouble with the Cuban regime over the naked woman’s picture.

“Korda made a mistake when he gave a copy to the Soviet poet Yevtushenko,” wrote Cabrera Infante in EL PAÍS. The image of a machine gun nestled between two breasts did not go down well at the Soviet embassy in Havana, and six years later Korda’s studio was sealed by the authorities. His photographs, contact sheets and negatives were seized.

In order to include the famous picture in his book, Acosta was forced to enlarge a still shot from a recording he found of the inside of Korda’s studio.

An entire chapter of the book is devoted to Herman Puig, who left Cuba in 1957 and spent most of his career in Paris and Barcelona.

It was not until 1927 that magazines finally published a collection of female nudes by photographers from various countries

“He created high-quality nudes, and his images are reminiscent of Mapplethorpe, except that Puig predates him,” notes Acosta.

The writer Vicente Molina Foix says Puig’s male nudes are “as stylized in their lighting and their poses as they are resoundingly carnal.”

In the 1980s, the new photographers “adopted the codes of modernity.” This means that they “began to use the human body to express rebellious ideas about religion, feminism or the gay community, for instance,” explains Acosta.

Discrimination also went out the window. Until then, the vast majority of models had been white. From that moment on, black and mixed-race individuals were also esteemed as models.

Acosta names some of the most relevant photographers of the last couple of decades: Marta María Pérez Bravo, Abigail González, René Peña, Cirenaica Moreira, Juan Carlos Alom and Jorge Otero.

The author believes that the recent thaw between Havana and Washington “could be stimulating” for Cuban art photographers. “Their main market is the collectors and the art galleries, and those are in the United States.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.