The man who “rejuvenated” Gaddafi

Brazilian surgeon recalls the time the Libyan dictator summoned him for an operation

When Brazilian medic Liacyr Ribeiro was invited to the First Arab Plastic Surgery Conference in the Libyan capital of Tripoli in 1994, he imagined it would be much like many others he had attended around the world. “I went to talk about breasts,” says the 73-year-old at his private clinic in Rio de Janeiro’s upscale Botafogo neighborhood shortly after saying goodbye to a young woman who had come with her mother to find out more about gluteal implants.

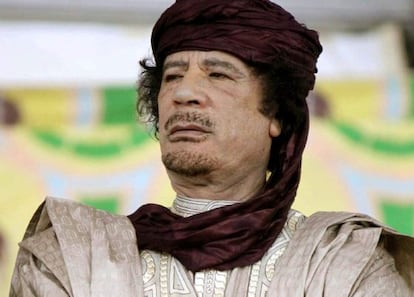

But on the second day of the conference, he says he was asked by a Libyan colleague if he could examine a “friend,” and soon found himself in a vehicle being driven by the country’s then-health minister – also a plastic surgeon – “along strange routes, crossing check points: all very secret.” The patient turned out to be none other than Muammar Gaddafi, the colonel who had ruled the oil-rich nation with an iron fist since taking power in a coup in 1969. “He told me: ‘You have to operate on me.’ He was in a big hurry. I didn’t know what was going to happen to me.”

He told me: ‘You have to operate on me.’ He was in a big hurry”

He was well looked after, but Ribeiro says he still feels the fear that gripped him during that first meeting: “He was the owner of the country, they could do what they wanted with me!” The surgeon describes Gaddafi as well mannered, cultured, and friendly, and someone who knew a great deal about plastic surgery. “I was impressed. But then few people lead a revolution aged 27.”

The colonel wanted to be operated on immediately, while Ribeiro attempted to explain that “this wasn’t how things were done.” The medic went back to Rio, packed his instruments, and returned to Libya with his assistants a couple of weeks later. “There was something unpleasant about operating on somebody like that: if something goes wrong, would I get out alive? There are stories about surgeons who operated on monarchs who were killed so as to prevent the story getting out,” says the medic.

The hospital where the surgery was carried out had been built in an underground bunker. “The operating room was far better than the majority I had seen during my travels around the world,” says Ribeiro. Fitted out with the most up-to-date German-made equipment, he noted that there wasn’t a single Libyan working there: “The anesthetists, the auxiliaries, the nurses: they were all foreign.”

There was something unpleasant about operating on somebody like that: if something goes wrong, would I get out alive?”

The operation was carried out under local anesthetic: “Gaddafi was terrified of going into a coma and that he would be unplugged.” Ribeiro says that for “ethical” reasons, he cannot reveal exactly what he did to Gaddafi, but was told by the leader that he wanted to be “rejuvenated”. On the last day of the post-operation recovery period, Ribeiro was handed an envelope filled with “enough Swiss francs to buy a very expensive car.” Gaddafi was pleased with the operation it seemed, and called Ribeiro several years later, shortly before he was overthrown: “But I had no desire to return, so I made my excuses.”

Ribeiro studied under Ivo Pitanguy, one of the pioneers of plastic surgery in Brazil, a country that has always been a leader in this area, and is a former president of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery. Speaking from long experience, he says that the increase in the number of plastic surgeons in recent years brings with it potential dangers. “Some upstart can put tiny noses on big faces or double D cups on a tiny body. This increase has not been a good thing: a lot of people are only interested in money. Breasts, abdomen and liposuction operations can be hidden, but not the face. And there are a lot of disaster areas out there.” His expertise is why Gaddafi chose him.

The surgeon cites three reasons why Brazil is the country where more people go under the knife than any other: “First, the vanity of Brazilian women. Second, the absence of any kind of secrecy, meaning that women even boast about their breasts in the waiting room. And third, the cost.”

Pitanguy says Brazilian women have always been “big-assed with small breasts,” but that tastes have changed. Ribeiro puts this down to globalization. “Women used to come to have breast tissue removed, now they want implants. The culture has changed: they want everything big.”

Ribeiro refuses to talk about another of his high-profile clients, former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi: “He’s still alive and active.” But he will say that he operated on the former Italian leader “before he took office, and that he has been operated on twice since then. He was a very easygoing guy,” he adds, laughing: “Sadly, he never invited me to any of his parties.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.