Madrid’s hidden fossil trail

The capital’s streets, walls and subway preserve all manner of paleontological remains

Few of the people who wait for the subway every morning at Madrid’s Ciudad Universitaria station are aware that the black limestone that lines the platform walls guards remains of the shells of ammonites, distant relatives of today’s octopuses.

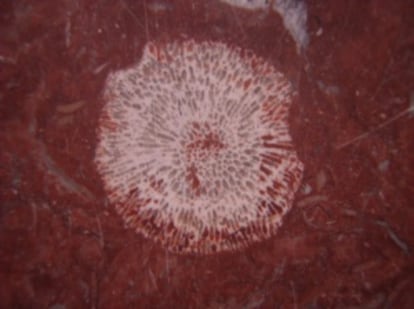

Similarly, not many of those who pass by the entrance to the old Mercado de Fuencarral, in the Chueca-Malasaña neighborhoods, know that the paving stones feature a colony of coral barely bigger than a one-euro coin.

Madrid preserves numerous fossilized vestiges of life as it was millions of years ago on its streets, building façades, and even in the depths of its subway system. The trouble is knowing where they are.

Now, however, a website has brought together information about these locations in an open, free and collaborative database.

“Urban fossils reflect the history of a city and its changes,” explains Rubén Santos, the geologist behind Paleourbana. “Many cities are real geology museums.”

Urban fossils reflect the history of a city and its changes. Many cities are real geology museums”

The project began three years ago under the name Caracoles en las aceras (Snails in the sidewalks), and has since grown to become a vast resource containing information on 259 points of interest in 53 cities in 10 countries.

The data is the fruit of Santos’ research and the information he receives from site users, who include everyone from professionals linked to the world of geology, to science teachers and “children who head out with their parents in search of fossils.”

Paleourbana highlights 16 points of paleontogical interest in Madrid. The fossils are hidden in subway platforms, in doorways, on the outside of a pharmacy, and even on tourist landmarks such as the Cervantes statue in Plaza de España. But to spot them, you need to train your eyes: “The first thing you need to do is learn to identify sedimentary rocks, which are the only type of rock that can preserve fossils. And then you look for irregular shapes, textures and colors in the stone."

In urban areas these sedimentary rocks are almost always limestone, which is not particularly common in Madrid, where granite has traditionally been the construction material of choice, Santos explains. “Almost all the fossils in the capital come from elsewhere. A lot of limestone has been brought here from the Basque Country and from Valencia and Murcia, which preserve fossils from the Cretaceous Period.” The indigenous remains come from the southeast of the Madrid region – limestone that formed in the bottom of lakes and today guard carapace remains.

Urban fossils preserved in construction stone are “outside their geological context,” Santos explains. They have lost “part of their paleontological value,” but that doesn’t deprive them of usefulness – they can still provide information about where they were formed and in what era.

That geological trace also reveals the history of a city’s construction. “They reflect how trends and techniques have gone on changing. The oldest buildings, for example, are built with stone from nearby areas, as back then materials could not be transported very far.”

This huge database also serves another purpose. “It allows fossil fans to have a kind of virtual collection without having to destroy the paleontological heritage,” says Santos. Simply by heading out on to the street, you can discover and photograph them, so as to later treasure them on the internet.