Bilingualism: the best workout for your brain

People who speak more than one language use their minds more, scientists say

A bilingual brain works like a traffic light. When it needs to choose, say, a Spanish word, it gives the green light for that language to move forward, and uses a red light to halt the term in English. This natural selection process, carried out hundreds of times every day, gives the brain a continual workout.

The effects on the brain of being able to speak two languages fluently have been the subject of continual and intense analysis within a range of disciplines over recent years. Some research suggests that speaking two languages helps prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s or senile dementia.

Two US teams are now studying the advantages that speaking a second language can give us in our everyday lives. “Bilingual brains are better equipped to process information,” says Professor Viorica Marian, a psychologist based at the Evanston campus of Northwestern University, Illinois, who has just published the results of her findings in the journal Brain and Language.

The perfect time to learn a language

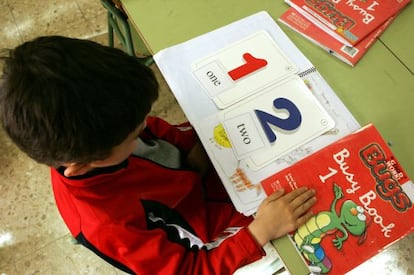

Patricia K. Kuhl and Andrew N. Meltzoff of the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences say the earlier we start to learn a new language the better. “The brain of a child up to the age of seven adapts easily to any innovation. During this time, he or she will notice, for example, if his or her grandmother speaks a third language and pick it up naturally,” says Meltzoff. “If you take you kids on holiday to another country, it is likely they will return knowing several words related to soccer after playing a game with other kids, while you will have learned nothing by spending time with their parents,” he says.

The pair says that from the age of eight, our ability to learn becomes “slower and more academic.” From this point on, the challenge of picking up language is more difficult to overcome. “If you are reading this and you’re an adult, it’s too late,” jokes Meltzoff.

But Professor Viorica Marian of Northwestern University says it’s never too late to learn a language. She grew up speaking Romanian and Russian, and her third language is English, although she can also get by in Spanish, French, and Dutch. She accepts that language learning is easier in childhood, and that the earlier we learn, the less of an accent we will have, for example, but she insists that we can also improve our control of the brain’s inhibition function “in a couple of months,” allowing us to learn another language more quickly.

Meanwhile, the University of Washington’s Institute for Learning and Brain Sciences, in Seattle, is working along similar lines in partnership with the Madrid regional government’s education department, and will be undertaking a study at several schools in the Spanish capital next year to assess the way infants under the age of three learn languages.

Both teams are focusing on the parts of the brain that speakers of one language activate, compared with those set in motion by fluent speakers of two or more languages. The study carried out by Dr. Marian of Northwestern was on individuals aged between 18 and 27 chosen by the University of Houston. Of these, 17 were bilingual in Spanish and English, while the remainder spoke only English. “We chose those languages because that form of bilingualism is more common in Texas, although we suppose the results would be similar for other languages,” says Marian.

The research, carried out over three years, was based on a simple experiment. After hearing a word in English, read by a man with a neutral accent, members of both groups were shown a drawing with four objects: two that were pronounced similarly in English, and another two that sounded totally different. For example: clown and cloud; candy and candle; or pig and picture. While the participants decided which was the correct term, the team looked at their brains’ behavior using magnetic resonance imaging.

The more oxygen and blood that flowed to the area of the brain involved, the more work was being carried out in that part of the brain. The inhibitory control areas were more active in the case of those who only spoke one language, as opposed to the bilinguals: “The monolinguals had to work harder to come up with the answers,” says Marian.

So what advantages do bilinguals enjoy? Professor Marian says children who can speak two languages fluently are able to concentrate better, a facility that stays with them throughout their lives: “If you are driving, or performing surgery, it’s important to be able to focus on what you’re doing and cut out extraneous noise,” she explains.

The brain of somebody who speaks two languages is much more flexible, it’s more used to complexity” University of Washington researcher Patricia K. Kuhl

The Seattle-based researchers, led by Patricia K. Kuhl and Andrew N. Meltzoff, are also looking into the brain activity of their own children, all of whom are bilingual. “The brain of somebody who speaks two languages is much more flexible, it’s more used to complexity, and so looks for the best solutions and as a result ends up more agile,” says Kuhl, who along with Meltzoff, was in Madrid at the end of September to visit several of the city’s bilingual schools.

Most of Spain’s regions are now moving toward a bilingual, English-Spanish education system. Earlier in the year, a Spanish delegation comprising, among others, Education, Culture and Sport Minister José Ignacio Wert, along with secretary of state for education Montserrat Gomendio and Lucía Figar, the head of the Madrid regional government’s education department, was in Seattle to visit the project.

Kuhl and Meltzoff have presented their research to the US Congress: “Our findings should help society to overcome its fear that a child who grows up with two languages does so at the expense of their maternal tongue, and also that this has a negative impact on other studies,” says Meltzoff.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.