The 1,001 faces of Nikola Tesla

Madrid’s Fundación Telefónica devotes a major show to the multifaceted scientific icon

It was the three-year-old Nikola Tesla’s cat that famously first introduced him to the marvels of electricity. “In the dusk of the evening, as I stroked Macak’s back, I saw a miracle that made me speechless with amazement,” he remembered later. “Macak’s back was a sheet of light and my hand produced a shower of sparks loud enough to be heard all over the house. My father was a very learned man; he had an answer for every question. But this phenomenon was new even to him. ‘Well,’ he finally remarked, ‘this is nothing but electricity, the same thing you see through the trees in a storm.’”

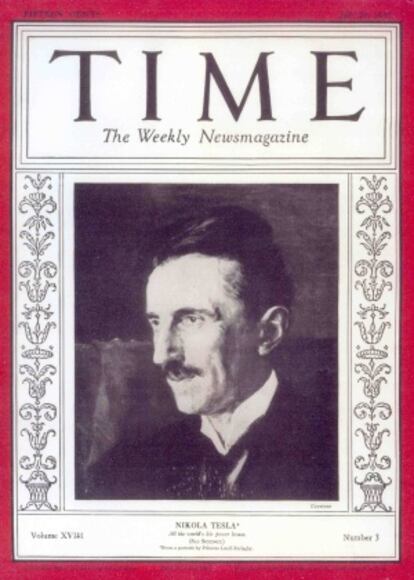

Over a century later, and Macak the cat has his own Facebook and Twitter accounts and Tesla (1856-1943), the father of the modern alternating current electricity supply system, is a pop icon. The Fundación Telefónica’s new exhibition, Tesla. Suyo es el futuro (or, Tesla: His is the future), which runs until February 15 and claims to be the biggest to date on the scientific genius, reveals both the iconographic face and the many others of this celibate inventor who has captured the collective imagination.

“We wanted to show Tesla as a living person, not as a historical fact,” says exhibition curator Miguel Ángel Delgado, who has also written several books on Tesla. A stroll round the display highlights the prophetic side of the inventor, with each of the 13 sections making up the display – “The archeologist of light;” “Tesla pop;” “Tesla, ideas like lightning” … – introduced not with a text by the curators, but in Tesla’s own words: “The progressive development of man is vitally dependent on invention;” “The future, for which I have really worked, is mine;” “It should be possible to project on a screen the image of any object one conceives and make it visible.”

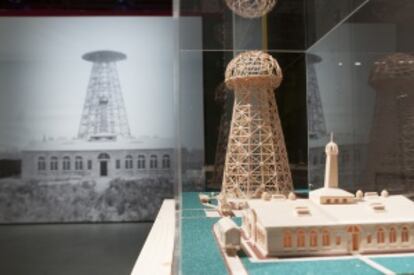

Tesla’s most radical predictions come in the section devoted to Wardenclyffe, the first of the innumerable towers he built in order to try to generate a “World System for the transmission of electrical energy without wires.” His own description of the project makes it sound like a carbon copy of the modern internet: “It makes possible not only the instantaneous and precise wireless transmission of any kind of signals, messages or characters, to all parts of the world, but also the inter-connection of the existing telegraph, telephone, and other signal stations without any change in their present equipment. […] An inexpensive receiver, not bigger than a watch, will enable him to listen anywhere, on land or sea, to a speech delivered or music played in some other place, however distant.” The exhibition also includes a model, graphic archive and a three-dimensional recreation of the Nikola Tesla Museum in Belgrade.

But the curators also wanted to show his fallibility. “In his later years his mind went and he said absurd things,” says Delgado. “Tesla is someone who is very human.” Among those foibles was his way of dressing. As soon as you enter the show you’re presented with a glass case containing his shoes, bowler hat and gloves – all made to measure and ready to be thrown away. He was obsessed with neatness, forever replacing barely worn gloves with new pairs: “He used 20 napkins per meal,” says co-curator María Santoyo.

Tesla was also obsessed with the number three and, despite his success with women, became voluntarily celibate so as to be able to carry out his research peacefully. “He was pigheaded. He never believed in the theory of relativity,” says Delgado. Oddly, though, Einstein never held it against him: on the occasion of Tesla’s 75th birthday the German genius devoted these words of praise to him: “I congratulate you on the great successes of your life's work.”

The exhibition mixes the fruits of that devotion to invention with details from Tesla’s biography, age and legend. “We have laid out the show from a conceptual point of view, making it clear that Tesla was a man of his time, not isolated from it.”

That aim is best displayed in the most important section of the exhibition: the one devoted to Tesla’s inventions, “The laboratory.” A circular cell, which evokes his laboratory in Colorado Springs, plays host to an overview of his inventions: a remote-controlled steam boat, his induction motor, his alternating current research, the Niagara hydro-electric power plant, his designs for a vertical take-off aircraft … But there, too, are his excesses, which include a death ray, which he announced in 1934 and offered to the US government, prompting a The New York Times front page.

Concluding the show is the “Tesla Pop” section, an anything-goes collage that surveys how he has been represented in films and videogames and how he has been reinvented by multiple fans. Everything from cupcakes to interviews with the likes of director Terry Gilliam and Christopher Priest, author of the novel that filmmaker Christopher Nolan adapted into the movie The Prestige, is here. Nevertheless, the curators are keen for visitors not to lose sight of the gap separating myth from reality: the second section, “The archeologist of light” features a sand pit with several light bulbs that turn on in front of numerous mirrors that multiply their shine – a recreation of a famous scene in The Prestige that features in the film’s trailer. Next to them, though, is a photograph showing what really happened: Tesla did indeed manage to send a current through the earth to illuminate some light bulbs – but just three of them.

Nikola Tesla. Suyo es el futuro. Until February 15 at Espacio Fundación Telefónica, C/ Gran Vía, 28, Planta 7ª, Madrid (entrance at C/ Fuencarral, 3, Madrid). http://espacio.fundaciontelefonica.com

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.