Where Spain’s foreign communities head to get their news

Newspapers aimed at Chinese and Romanian readers offer an alternative take on current affairs

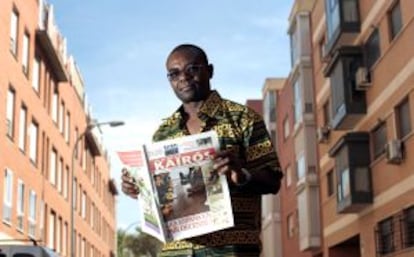

With headlines such as “The king gives up the throne before it gives up on him,” and “Podemos: The little parties grow toward the two-party system,” monthly newspaper Afrokairós tries to explain Spain to the country’s African residents. “The big media organizations don’t include our point of view,” explains its Congolese editor Bakala Kimani, under a sun shade in the small garden of the house in Aranjuez, 40 kilometers outside Madrid, that serves as the paper’s offices. “They only call immigrants when they are talking about immigration, but we are fully legal citizens and we have opinions on a range of issues.”

Set up a little over a year ago, Afrokairós is one of the latest publications for foreign residents and nationalized Spaniards from other countries to spring up in a sector that emerged in the 1990s, reached its peak in the middle of the 2000s, and has evolved alongside the communities it serves. “Now we are more integrated, we don’t talk so much about immigration,” explains Bulgarian Bogdana Maradzhiyska, who studied journalism at Madrid’s Complutense University and helped set up Romanian and Bulgarian weeklies Noi in Spania and Nova Duma a decade ago. “More than immigrants, I see our readers as self-employed workers who are most interested in tax policy,” she explains.

To help encourage integration, many of the foreign newspapers devote their front sections to stories about Spanish politics, which sit side by side with others with a more specific reach. For instance, the front page of freesheet El Periódico Latino recently led with a story about the death of former Spanish Prime Minister Adolfo Suaréz alongside a piece about Latin American participation in the World Soups Festival in Barcelona.

What are the subjects that most interest foreign residents in Spain? That depends on where they come from and where they settle down. The Latin American and Arabic press talks most about Catalonia’s sovereignty plebiscite because there are large communities of both in the region, while the Romanians and Chinese focus on economic stories that affect small-business owners.

Topics are always tackled from a certain viewpoint: a recent editorial in Arabic newspaper Andalus Press considered the right of imams to argue in favor of Catalan independence, while a special report about the European elections in El Periódico Latino focused on the “participation of the Latin American community.” Afrokairós underlines the silence from the African embassies over the immigration crisis in the Strait of Gibraltar and at the borders of Spain’s North African exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla. “Our governments are as responsible as the Spanish one is, but here the press doesn’t criticize them because it succumbs to a certain paternalism towards Africa,” says Cameroonian journalist Simon Nong.

What most of them do agree on is what doesn’t interest them. “We don’t get into the political rows, the minutiae going on in the party trenches, all that blah blah blah stuff that even bores Spanish readers,” says Said Ida Hassan, who was the Madrid correspondent for official Moroccan news agency MAP before he set up Andalus Press, which is distributed in consulates and mosques across Spain to keep the country’s second-biggest community of immigrants informed. (Of Spain’s five million immigrants, 771,427 are Moroccan and 795,513 are Romanian, according to the National Statistics Institute (INE).)

“Why is there so much about Pedro Sánchez [the new leader of Spain’s Socialist Party] on TV and on the front pages of the newspapers?” asks Bogdana Maradzhiyska. “The issue was overexposed. If Sánchez does something that affects the life of Romanians tomorrow, then we will publish something about him.”

Sánchez did sneak on to the front page of monthly Ocio Latino, which is now 20 years old and has a print run of 30,000 copies, thanks to one promise he made: that he would include immigrants on the next local and regional electoral lists. “Because of the language, Latin Americans are more exposed to the Spanish media. They already know who Pedro Sánchez is. We have to tell them how he affects them,” says the paper’s editor, José Luis Salvatierra. “Our publishing schedule means we cannot compete in the maelstrom of news; we have to link the story directly to readers.”

Podemos party leader Pablo Iglesias has recently had the most success in crossing the media frontier. His party’s success in May’s European elections was reported in almost all the foreign-aimed media with the same surprise as it was in the Spanish. “Pablo Iglesias, dark horse of the European elections,” read the headline in Chinese weekly Ouhua.

“We see politics outside of the field of play; we don’t take sides,” explains its editor Xinyi Tao. Ouhua has a solid nationwide distribution network made up of the stores and supermarkets owned by members of Spain’s 185,250-strong Chinese community. Economy and immigration policy are what most interests them, but the paper’s 80 pages have room for more: up to 60 percent of the content is stories about Spain, compared with around 40 percent international news (the proportions are the reverse in other publications). “The Chinese community isn’t as closed off as you think,” says Tao, whose editorial team – one of the biggest, with 18 staff members – works out of a modern Madrid office block. “We are very keen to integrate, we want to know about the country we are living in. We’re interested in everything from what laws there are, so as to comply with them, to what the festivities are like, so we can join in with them.”

The Spanish media only call immigrants when they are talking about immigration, but we have opinions on a range of issues”

The reality of a story such as King Juan Carlos I’s abdication depends upon the prism through which you look. “Your problems are ours, though we don’t feel some of them so closely: neither Romania nor Bulgaria are monarchies, so we didn’t get too crazy about that story,” explains Maradzhiyska.

But the monarchical handover did fill a lot of pages of Andalus Press. “For Arabs the monarchy is something untouchable. We wanted to explain that other types of monarchy exist, where kings abdicate and admit their mistakes, and that this could also happen in our countries,” says Said Ida Hassan.

Afrokairós headlined one of its stories: “Felipe VI turns his back on Africa,” accompanying it with a photo of the new king from behind. “He didn’t mention Africa in his speech and avoided the topic of immigration, and no media outlet criticized him for it …” says Simon Nong. “In Spain there was a pact not to touch the king dating back to the Transition, but we come from countries where you can only publish the official speech, so we are not going to censor ourselves here.”

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.