Madrid exhibitions turn the final page on tale of Spanish ship’s treasure

New shows tell story of the Mercedes’ 1804 sinking and the legal battle to recover its hoard

On the morning of October 5, 1804, a British naval squadron came across a group of four Spanish frigates off the southern coast of Portugal, close to the port of Cadiz. The two countries were not yet at war, but the British, aware that Napoleon would soon force Spain into a conflict, engaged the Spanish forces, capturing three of the ships, while another, the Nuestra Señora de las Mercedes, sank after her magazine exploded, killing an estimated 265 people and taking a vast hoard of bullion down to the seabed.

And there she would remain, forgotten for more than a century, until US deep-sea treasure hunting company Odyssey located the vessel in 2009 and removed around 600,000 mainly silver coins, along with other items.

When the story broke, the Spanish government of the day, under Socialist Prime Minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, immediately claimed ownership, and the affair soon became a matter of state, rallying the two main political parties in a rare display of unity.

Two new exhibitions in Madrid, one at the National Archeology Museum, and another at the Naval Museum, not only provide historical context to the sinking of the Mercedes, but also tell the story of the legal battle to get the coins returned.

From a legal point of view, the affair ended two years ago after the Supreme Court ruled that as the Mercedes was a warship on a mission of state, the treasure aboard her was Spain’s. Two Hercules military planes were sent to an army base in Tampa to bring the coins back. The Culture Ministry decided that the best place for them to be seen was at ARQUA, the National Sub-Aquatic Archeology Museum in the Mediterranean port city of Cartagena, where a permanent exhibition area has been created.

The exhibition at the Naval Museum tells the story of Diego de Alvear, the second-in-command of the Spanish squadron, whose wife was aboard the Mercedes, along with seven of his children. He was later compensated by the British for his loss. He went on to remarry, tying the knot with an Irishwoman called Lisa Ward, and have another 10 children. One of his sons from his first marriage fought for Argentinean independence a decade later. Several personal items belonging to Alvear are also on show, including his telescope, a portrait of his second wife, a saber and a theodolite. At the time of the encounter with the British, Alvear was returning to Spain with his family, and had been appointed second-in-command of the squadron by José de Bustamante, the commander of the convoy.

At the time of the sinking, Spain was not officially at war with Britain, having signed the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, along with France and the Batavian Republic. Taking advantage of the truce, the Spanish government of the day had sent the squadron to the Americas to bring back badly needed silver and gold. The original treaty document is among the papers included in the exhibitions, and was used by the Spanish authorities in their fight to recover the bullion taken by Odyssey.

When the Spanish squadron, led by Bustamante, left Montevideo for Cadiz, it was assumed that Spain’s neutrality in the latest French-British conflict would be sufficient to allow it safe passage. But the British feared that the money the squadron was carrying would be used to pay the French. Spain had signed the Treaty of San Ildefonso with France in 1796, pledging to become allies and fight Britain. In the meantime, Spain was obliged to pay the French until it declared war on Britain. The British were waiting for the four vessels – the Fama, Medea, Clara and Mercedes – as they approached Cadiz. The battle that followed is explained from the perspective of 10-year-old Tomás de Iriarte, a boy soldier, and illustrated through 30 watercolors. The British first invited Bustamante to surrender, which he refused to do, and so fired a warning shot across the bow of the Medea, and then, at close range, opened fire on the Mercedes.

Iriarte carried gunpowder for the cannons, but was soon told to go below deck with the civilian passengers. Soon after, a cannonball hit the Mercedes’ magazine, which exploded and sank, taking with it its bullion, 1,500 kilograms of quinine that would have been used to combat a yellow fever epidemic in Spain, along with wool, cocoa, and other products.

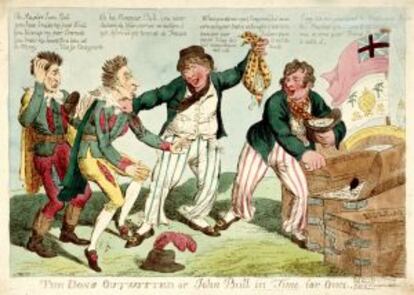

The three other vessels were captured, and taken to the British port of Gosport. Their haul was even greater than that of the Mercedes. The encounter made headlines in Britain, and engravings and newspapers from the time are included in the exhibitions. Shortly afterward, Carlos IV would declare war on Britain. A year later, the combined French and Spanish fleets would be destroyed at the Battle of Trafalgar, close to where the Mercedes was sunk.

Among the 200 items on display at both exhibitions (borrowed from 27 collections, including that of the National Portrait Gallery) are a 1799 encyclopedia of American fauna from the Museum of Natural Sciences, a scale model of the Mercedes, a collection of drawings depicting the battle, and the centerpiece, around 30,000 restored silver coins piled up in a mirrored case.

Carmen Marcos, the curator of the exhibition at the National Archeology Museum, and an expert on coins who advised the Spanish government during its legal battle to get the hoard returned from the United States, explains that the silver pieces, extracted from mines in Spain’s colonies, were “the driving force behind the modern economy.” A number of examples of coins that were restamped with the image of Britain’s King George III are also included. “These were the dollar of their day,” says Marcos.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.