Spain’s forgotten jet-engine genius

If he had not become a victim of the Civil War, Captain Leret would now be in the history books 78 years after his death, a model of his invention has gone on display in a Madrid museum

On the day they killed him, Virgilio Leret was 34 years old and on the verge of making history. Today his name, which doesn’t even appear on a headstone as nobody knows where he was buried, would be in the encyclopedias and perhaps even on the odd town square if he hadn’t been shot at the start of the Spanish Civil War on the night of July 17, 1936 – “the first shots that would ignite the world,” in the words of his widow, the Mexican writer Carlota O’Neill.

In 1935 he had been granted the patent for his invention, “the turbo-compressor continuous combustion engine” – the first Spanish jet engine. The prime minister of the Republic, Manuel Azaña, had given the order for production to begin in September 1936 at the manufacturing plant of Hispano Suiza de Aviación, but by then Leret had already been dead over a month.

Seventy-eight years later, his daughter Carlota has finally managed to get his creation exhibited in a museum – though she had to pay for the model out of her own pocket.

Had he not been shot, “his engine would surely have become a reality, with the resulting honor for its creator and for Spain,” wrote the aeronautical engineer Martín Cuesta in the 2002 issue of the Ministry of Defense's specialized publication Aeroplano, after carrying out a detailed study of Leret’s plans.

“He was one of the most brilliant officers in the armed forces,” wrote Hispanist Paul Preston in his book The Spanish Holocaust.

Captain Leret was commanding the Atalayón hydroplane base in the Spanish north African exclave of Melilla when the Regulares (volunteer units of Moroccans in the Spanish Army who joined Franco’s rebellion) launched a surprise attack on July 17, 1936. He defended it knowing it was a lost cause – many men were on leave owing to the fact it was the height of summer and a Friday – until the ammunition ran out. Then, Leret was executed by his own soldiers, who were forced to shoot their captain in order to strike terror into everyone else.

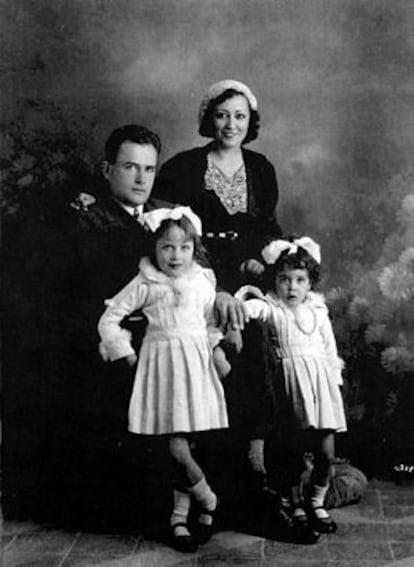

Only a short distance away, Leret’s wife and two daughters had been listening to the gunfire the whole afternoon. They had arrived 15 days before to spend the summer with him on a boat anchored in front of the base. They didn’t even have time to say goodbye. “My father took his gun and cap and left. We never saw him again,” remembers Carlota, who was then just a child.

“Virgilio rowed and rowed, getting further and further away from me,” her mother wrote in her memoirs. “I stared at him and thought: ‘I want to look him hard in the face because I am not going to see it any more.’

His widow was imprisoned five days later. “By mistake they gave her my father’s suitcase containing the plans for the jet engine inside,” her daughter remembers. “Horrified by the idea that they might fall into the hands of the Francoists and used in the war against the Republicans, my mother hid them and finally got them out of the jail with help from two prisoners.”

One of the inmates who helped her mother was Ana Vázquez, who had been jailed for prostituting her daughters. As she knew nothing of politics, she had been put in charge of watching “the reds,” O’Neill wrote. The three copies of the technical drawings were smuggled out wrapped in dirty laundry and collected from Vázquez by the son of an inmate sentenced to 30 years after her husband had been shot.

O’Neill was tried three times by a military court and finally sentenced to six years, serving five of them. During her time inside, she feared for her life when a group of Falangists came into the prison asking for some female prisoners to kill to “celebrate” the taking of Toledo. She spent the whole night hiding in a water tank – “The water was up to my mouth, but I had two alternatives: drown or let myself be killed, and I preferred the first,” she wrote. From her hiding place, she heard the prison director say: “It’s madness to get rid of them all in a heap. When you want to kill women, come and get them, but one at a time!” The Falangists “went off taking as many as they could carry in their hands,” O’Neill added.

In 1941, following her release, O'Neill went to the house where the plans had been hidden, under a floor tile, for the last five years. She thought her husband’s invention might be able to help the British defeat Hitler. She and her mother took one of the copies to the British embassy to give them to aviation attaché James Dickson, who was to die in an accident a short while later. She never found out what happened to that copy, but she never let go of the other two. Whenever she traveled away from Caracas, where she settled down as an exile after regaining custody of her daughters, she always took the drawings with her.

After her death in 2000 at the age of 90, her daughter Carlota started to show them here and there, hoping to find recognition for her father. Spain’s AENA national airports authority financed a documentary about the story in 2011, and the Museo del Aire aviation museum in Madrid is now displaying a model of his invention. But it has not been easy.

“They were excited at the museum, but told me they didn’t have the money,” Carlota says. She doesn’t want to reveal how much she has invested in building the model of the turbo compressor, which comprises 2,674 pieces and took 2,500 man hours to build: “I don’t want people to think I am crazy,” she says. A small part of the replica has been financed through the rights to O’Neill’s memoirs: 391 pages of prison, exile and poverty that are, above all, a long declaration of love for her husband, probably the first victim of the Spanish Civil War.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.