The soccer player who blew the whistle on corruption in the sport

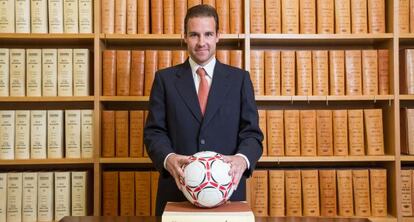

At 27 professional footballer Borja Criado decided to retire from the sport and study law Now a notary, he has chosen to tell his story about the dark side of the beautiful game

Five years ago, when Borja Criado turned 27, he decided he was tired of playing soccer for a living. He had just been sanctioned after being found guilty of doping: the substance in question was part of a treatment for hair loss. So he left his club, Granada 74, then playing in the Spanish second division, and began studying to become a public notary. After passing his exams in February, he has now decided to reveal some of the secrets of the dark side of the game. He has no evidence, and refuses to give names; but he hopes his story will make younger players think twice about the sport.

“I’m not trying to create a scandal, I just want to sound a warning and try to clean things up a bit. I enjoyed playing, but I just got tired of the corruption in soccer,” he says. “We need to talk about this – I mean, games will still be bought, but let’s at least get it out in the open.”

Criado’s career was that of a journeyman: the peak came between 2006 and 2008, when he played three games for Valencia; he was then sold to second-division side Ciudad de Murcia, and then to Granada 74. “It’s a tough world in the Segunda. Many of the club directors are friends. It’s not uncommon for team owners to agree that this or that club needs more points and to fix the match accordingly. I saw that a lot. It’s very easy to fix a match, even when a striker gets a clear chance on goal: he can boot the ball into the stands; after all, even a player like Benzema misses now and then. Or you can just stick your hand out when you’re in the goal mouth during a corner, and bingo, it’s a penalty: game over.”

“It’s not uncommon for team owners to agree that this or that club needs points and to fix the match accordingly”

He says that he personally never benefited from the corruption around him: “It’s impossible not to know what is going on, and then you feel like you are involved, like it or not. You would learn from somebody that this or that club was going to lose. I had teammates who would gamble online, some of them were winning as much as €6,000 a month from betting.”

On one occasion the owner of a club told him: “The most important thing in managing a side is to have enough cash to be able to buy a few games at the end of the season so as to avoid relegation.”

Javier Tebas, the president of the Spanish Professional Football League (LFP), does not deny that match fixing goes on: “Uefa president Michel Platini has said that match rigging is the biggest problem the game faces. It is still a minority of clubs that do it, but it’s like an infection.”

Emilio García, a member of Uefa’s Control and Disciplinary Body, agrees that Spain has a problem. “This is something that in Spain has traditionally been about avoiding relegation, rather than illegal betting. That said, the one can lead to the other, which is why we are working with the police to keep a very close eye on Spanish games,” he says. The LFP has organized an awareness and education campaign for the 42 clubs in Spain’s top two divisions that includes videos of Belgian international Jean-François Gillet, whose career ended in disgrace last year after he was found guilty of involvement in match fixing.

Criado decided to air his experiences on law blog www.hayderecho.com after Granada player Dani Benítez tested positive for cocaine. He says that even as a boy, he felt uncomfortable at the pressure the game put on players. “I was 17 when the Barcelona youth team called me. Iniesta, Sergio García, Valdés, Nano, Arteta, they were still kids, but they had multi-million-euro contracts. I told the youth team directors that I wanted to study law, and was told that what I had to do was focus solely on soccer.” His family supported him when he decided to turn down the offer.

Valencia then contacted him. “It was very different. They found me a college, and I studied in the afternoons. My teammates would spend the afternoons playing or shopping. I used to ask them what they would do if they weren’t successful, or when they retired. How were they going to be able to study later on in life when they had left school at 16? If at 22 you realize that you aren’t going to be Maradona, it’s too late to take up studies.”

He says he bought himself a car with his first salary, and then an apartment; a modest outlay at a time when soccer clubs were making huge sums of money from property development, regional government subsidies and television rights. Many young players let the money go to their heads, he says: “There was a goalkeeper in the team who spent €30,000 on a Porsche. His contract fee was for €35,000. When he realized that he had to pay taxes on it, he ended up having to borrow money from the bank to get by.”

Things were going well for Criado at Valencia, then being managed by Rafa Benítez. But after he moved to Espanyol he tore his Achilles tendon, and was out of the game for six months. “I lost my speed, and was never really the same after that,” he says.

His career quickly waned. In 2007, during a routine anti-doping test, Finasteride, a compound used to combat hair loss, was detected. The Spanish sporting authorities ruled that Finasteride could be used to hide other substances, and he was banned from playing for two years, which on appeal was reduced to three months. That was when he decided to leave the game and start a new life. He spent the next few years locked in his room studying 12 hours a day, and says that he never wants to see another soccer match in his life.

“I saw firsthand the corruption that goes on in soccer. I was injured, and then unjustly sanctioned for doping. I lived the dream in reverse. I idealized soccer, but now I realize I was looking at it through rose-tinted spectacles,” he says.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.