Last stop Tangier

Morocco has taken on the role of guarding Europe's southern frontier Thousands of men and women's only chance of making it into Europe is by reaching Spanish soil

The Moroccan city of Tangier is now Europe's southern frontier crossing, doing the dirty work that the authorities on the other side of the Mediterranean are so desperate to avoid. The Spanish government has just published data that suggests that the number of migrants entering Spain fell in 2013 by 31 percent. The Interior Ministry admits that Morocco has played an important role in this, but fails to point out that its figures are in large part based on those which the authorities in Rabat have amassed on the number of men and women who have made their way from all over Africa, and who now wait for their opportunity to get into Europe.

Many organizations who work with migrants question the validity of those figures, which in any event do not show how many die trying, nor reflect the appalling living conditions of migrants, nor on how many die trying to escape from the police, as 16-year-old Cédrick Bete allegedly did in December by jumping out of a fourth-floor window in Tangier to his death. His friends collected his lifeless body and carried it to a border crossing, throwing it down at the feet of the dozens of armed police officers at the port who came out as they approached. Earlier this month 15 sub-Saharans died during an attempt to pass from Morocco into the Spanish exclave of Ceuta via the sea, a tragic incident which has put the spotlight firmly back on this migratory crossroads.

To the men and women who make their way into Morocco from all over Africa, when they arrive in Tangier it must seem as though they have already arrived in the first world: a modern, bustling city divided by wide, modern avenues lined with office blocks, and home to new residential suburbs like Boukhalef, on the way to the international airport. Laid out on a grid, it is still under construction, and many of the homes in its white apartment blocks have been paid for with money sent home by migrants working in Europe. According to official figures, growing numbers of the 2,000 apartments here, have been let out to men and women trying to make their way into Europe, while others have simply been squatted. What was planned by the city's authorities as a neighborhood for Morocco's emerging middle class has been turned into a multi-cultural refuge for would-be migrants, many of them, like Cédrick Bate, still in their teens, often without papers or passports.

Cédrick was well known in Boukhalef, spending much of his time at the makeshift telephone booth centers used to make cheap calls back home. Not everybody here has made their way by crossing the deserts on foot, or trafficked by gangs of organized criminals. Many reach Morocco by plane, or by bus and train. But they now all now face the same problem, and must decide whether to try to cross the Strait of Gibraltar to Europe in a rickety fishing boat or inflatable dinghy, make a bid to rush the fences surrounding the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, or make a life in Morocco, where they will be subjected to constant harassment by the police.

Cédrick Bete's death last year on December 4 was the third time an African migrant had died during a police raid. The outpouring of anger that followed was unprecedented in the country, bringing hundreds of men and women living in Boukhalef out on to the streets to protest.

The atmosphere in the weeks that followed was tense, and the police had clearly been told to avoid confrontation after video footage of their violent response to the protests was posted on the internet and picked up by the European media. Those living in Tangier enjoy a little more protection from the authorities compared to the men and women surviving in the woods and hills outside Ceuta and Melilla. There are stories of night-time raids, of police brutality, arbitrary arrests, and even murder. But in the city, word spreads fast, and the would-be migrants are increasingly prepared to confront the authorities.

Frank Elangue, aged 20, says he knew Cédrick. He lives in a tiny Boukhalef apartment with seven other people, among them a couple with a seven-month-old child, sleeping on a mattress on the floor.

Frank has little idea of what he would do if he were able to make it into fortress Europe, other than that he would like to work in Germany. Along with another young man who calls himself Kevin, he keeps a close eye on the weather forecasts, waiting for a calm sea. He has had to abandon one crossing, but said in January that he would attempt a second in the coming days aboard a small inflatable Zodiac dinghy, costing between 200 and 400 euros, and known among migrants as a "toy."

Rafael Lara of the Andalusia-based Human Rights Association says that last year saw an increase on 2012 of around 1,000 migrants making it to Spain, mostly in Cádiz province, on the Atlantic. "There has been a five-fold increase in arrivals there; and this despite the coastline undergoing increasing militarization. At the same time Morocco is collaborating much more with the Spanish authorities; the Interior Ministry there says that it has prevented almost 20,000 attempted crossings, but I think that is an exaggeration."

Binda is a young woman from Senegal who has moved from the hills around Tangier down into a tiny room in the city's historic Medina quarter. She waits there with her seven suitcases, knowing that she will have to sell their contents before she leaves. The only thing she needs is the inflatable dinghy she has bought. She has already made one crossing, when she was pregnant; she will now have to make the journey again with her baby.

Binda receives help from the Catholic Church in Tangier: she has learned how to make bracelets, which she sells to scrape a living. Clergy and lay helpers assisted her move from the makeshift camps in the hills outside the city, where she faced the constant risk of sexual assault. In the absence of Doctors Without Borders, which no longer operates in Morocco, the Church is the only institution that helps migrants. "We don't provide them with meals, because in Morocco, anybody can afford to eat," says Inmaculada Gala, described by her boss, Santiago Agredo, as a "guerrilla nun."

"We provide blankets and clothing, above all for the most needy, the people living out in the open in the hills," says Agredo, who has repeatedly expressed his opposition to the Spanish authorities' immigration policies, and who believes that the fences surrounding the exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla should be torn down and the borders with Europe opened.

He and his colleagues have to tread carefully in Morocco. "We cannot be seen to be proselytizing in a Muslim country; all we can do is to allow Catholics to receive communion, but when it comes to providing help, we make no distinction on religious or racial grounds. This is a very different approach to the Muslim Brotherhood, which only works with local Muslims; it doesn't help migrants. They would prefer it if we took the same approach, and only worked with Catholics," says one priest.

When it comes to getting into Europe, there really are only two options open to the thousands of African migrants growing in number in Tangier: scale the three-meter fences put up by the Spanish authorities around Ceuta or Melilla, or risk their lives aboard an inflatable dinghy. In reality, the numbers of people coming into Europe this way are insignificant compared to those arriving by plane, but they make far more headlines, giving the impression that Europe is besieged by desperate hordes of men and women that have been trafficked by criminal gangs.

In this context, European authorities feel justified in beefing up borders, militarizing the coastlines, and, in the case of Spain, subcontracting out to Morocco the job of policing its southern flank. Nobody knows how much money the EU or Spain pays Morocco to carry out this task. "There is absolutely no transparency on this," says Mikel Araguás, the secretary general of Andalucía Acoge (Andalusia Welcomes), an NGO that works with migrants who have made it into Spain. "It is difficult to make any estimates, because we don't know how the money is spent, or on what. There are so many funds within the EU that it is impossible to know where Spain's foreign policy in this regard ends and the EU's begins. For example, the military planes that Mauritania received a few years ago were listed officially as development aid. It makes no sense."

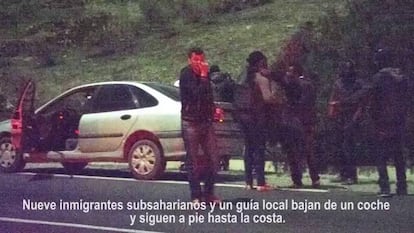

The beaches outside Tangier are now patrolled by military personnel. And just getting there is an expensive and risky business as a group of nine men found out one night in January. Aside from the cost of the inflatable dinghy they have already bought, they have had to pay 30 euros a head to a taxi driver who has stripped his Renault Laguna of seats to squeeze them all in. It may even be necessary for them to bribe the soldiers supposedly guarding the beach.

On this occasion, the group has been left half a kilometer away from the beach, and must make their way through the fields by moonlight down to the shoreline. They stop half way to drink some water, put on their life jackets, and stuff their phones into condoms to keep them dry, strapping their water bottles to their bodies. Two of the men carry oars, a couple of buckets to bail out the dinghy, and a pump to inflate the craft when they make it to the beach.

Every few meters they stop, led by a guide who knows the way, until finally they reach the beach, from where the lights of Gibraltar can be seen just 14 kilometers across the water... Europe.

They line up in two rows, the procedure familiar to many, who will have tried and failed to make the crossing before. One of the group begins to inflate the dinghy. As they wade out into the water and begin climbing aboard the fragile craft, the guide calls the Spanish coastguard service, warning of the imminent arrival in their waters of the latest group of migrants. But this strategy is no longer any guarantee of being picked up and taken to Tarifa. The Spanish authorities will no longer enter Moroccan waters to rescue vessels adrift in these busy shipping lanes, although no explanation has been given for the apparent change in policy.

Instead, what now seems to be happening is that that the Moroccan coast guard is working with its Spanish counterparts, and will instead pick up migrants. Fewer and fewer dinghies are making it to Spanish waters.

On this evening, the bid fails. Before the occupants of the dinghy can even begin rowing out to sea, a Moroccan military patrol arrives. There is no drama to the event; nobody tries to flee, instead they simply allow themselves to be rounded up and brought quietly ashore. Only the guide has the wits to bolt, disappearing into the darkness.

The nine men know what awaits, them: interrogation, and a long drive out into the desert, where they will be dumped somewhere at the expansive border with Algeria.

Survival in the hills

The woods and hills outside the Spanish exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla are home to hundreds of destitute men and women awaiting their opportunity to scale the fences that guard Europe's last outposts in Africa.

Bellyournech is a wooded area, part of a huge natural park, that rises upland in the area around Ceuta, and from whose hills mainland Europe can clearly be seen, a few kilometers across the Strait of Gibraltar. It seems a peaceful place, a haven, but venture inside and it soon becomes clear that its forest glades and caves are a temporary home to migrants from all over Africa trying to make their way into Europe. Nobody knows how many.

The woods are divided up along ethnic lines, with groups of Senegalese, Cameroonians, and other nationalities each occupying their own areas. There are two kinds of camp here: temporary ones that can easily be located by the Moroccan military, and others, scattered deeper within the forest, often in rocky outcrops and caves, that are more secure. There are people living here who have been trapped in Morocco for several years, with many failed escape attempts behind them, and who have now run out of money: people with no future, and with nowhere to go. "Everybody trying to make it to Europe is part of a family project," explains Migueles of NGO Aljaima, and who has worked with migrants for many years.

"The journey tends to take around three years, with the cost shared by all members, who have often invested everything they have," he says.

The only help the people living in Bellyournech receive is from volunteers like Migueles or Juanma Soria, who spends many hours each week trekking through the woods to distribute blankets, clothes, and medicine.

But word about attempts to storm the fences reaches Bellyournech, although the Moroccan police are always on the lookout for groups of men and women filtering out down the hillside to the border. "The police will park buses ahead of a raid, and will then drive people down to the south of the country to the border with Algeria. But it is an expensive business for the Moroccan authorities, and there are growing problems with Algeria," says one member of a local NGO.

In response, the inhabitants of Bellyournech keep a watch on the patrols, and have learned their routines and timetables, developing other strategies to avoid detection in what has become a game of cat and mouse.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.