“My pardon request was lost but this is not being investigated”

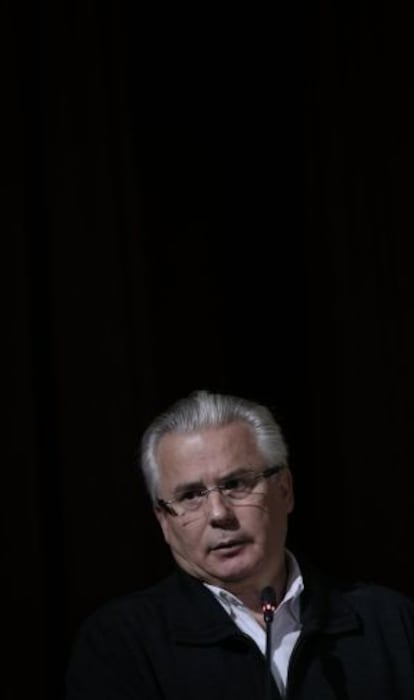

Baltasar Garzón talks about the state of the judiciary in Spain and his commitment to freedom of information and WikiLeaks

Baltasar Garzón, a High Court investigative judge suspended from his duties for 11 years for wiretapping Gürtel corruption network suspects and their lawyers in prison, speaks to EL PAÍS about the situation with ETA, the controversy over whether or not Princess Cristina should walk up the steps to court next month and the Justice Ministry mislaying a petition for his pardon for almost 18 months.

Question. What do you think happened to your pardon request?

Answer. The petition was filed by Medel [European Judges for Democracy and Liberty]. I replied within the required timeframe and told the Justice Ministry that I believed there were objective causes and that I was grateful for the petition. From that point, I disconnected. Later I learned that the file had been lost. The question is whether it was a mistake or there was intention behind it. The Justice Ministry, the Supreme Court and the Attorney General’s Office need to investigate. It is not acceptable that it was in limbo for a year and a half and it needs to be cleared up. The Gürtel lawyers oppose a pardon and I hold out little hope because the desire to aid justice has not been the driving force [in this case]. I will continue to keep fighting to show that no crime was committed, although I find it very depressing that in the face of such serious cases of corruption that are still being aired, there are those within the Popular Party making excuses.

If this had happened during a trial, there would be an immediate inquest"

Q. Has Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón called you to explain what happened?

A. No, and he has no reason to. And it’s normal; he has enough on his plate with his troubles and the decisions he has to make to call me. What is not normal is that it not be investigated. If this had happened during a trial and a document was lost for a year and half there would be an immediate inquest, with the General Council of the Judiciary involved.

Q. If you are pardoned, will you return to the bench?

A. My title remains magistrate-judge. When the period of suspension expires or there is another circumstance that ends it, I will make a decision from there, which will not be necessarily to continue as a judge. I am doing other very interesting things in the sphere of justice, including trying to see how a profound change within the system from the point of view of victims and lawyers can be brought about, to detect the deficiencies that exist and to fight against judicial corporatism, which is one of the biggest cancers in the judicial profession. I am also involved in criminal and right-to-information processes. I conducted the defense of Julian Assange and WikiLeaks and I believe this a field where it is absolutely necessary to find a balance between the rights of citizens and of the right to a presumption of innocence.

The princess's lawyers and the Royal Household have not done what is best for the public"

Q. Has the Nóos case involving Princess Cristina and her husband, Iñaki Urdangarin, demonstrated that justice is not equal for everyone?

A. Every case can demonstrate that justice is not the same for everyone. It depends how it is treated, how the investigation unfolds on the part of the judge and the prosecutor… There are times when the public importance of the news can lead to the resolution being influenced. That a judge has had to produce a legal treatise of 220 pages in order to call a witness is not normal; something isn’t working. It should not be necessary because naming someone as a suspect is merely information, all of their rights are guaranteed and they have access to all the documentation. But in other instances people are named as suspects without quite knowing why. Judges have an obligation to impart justice equally. This is not to say that they should be harder on people with more resources or softer with the more vulnerable but that they should apply the law as they find it and that, unfortunately, is not always the case.

Q. Should the princess be made to walk through the front door of the court when she testifies?

A. That doesn’t interest me particularly; what is important is what happens inside. In this case, her lawyers and the Royal Household have not done what is best for the public; there has been no transparency, but in general what concerns me is the stigmatization of the people involved. Nobody should pull their hair out because they have been asked to give their version. […] How one enters a courthouse depends on security, mobility… the judge must decide. I have authorized people to enter through the garages when the investigation has been under secrecy orders or when there were protected witnesses. But once inside, all people are equal. The chief of security should make his decision and that should be the end of it but in this country we make a joke out of everything and create problems where they don’t exist, starting with Minister Gallardón who, for reasons I don’t understand bites off more than he can chew. The minister should do his job: being the justice minister.

Q. What do you make of ETA’s latest pronunciations, that its inmates have accepted penitentiary jurisdiction?

A. We have now witnessed two years without terrorist violence. I believe that this is the moment for us to move toward the definitive end of ETA. We must ask ETA and its supporters to keep taking steps and we must also take steps. In a solution of transitional justice the victims must be present; they must participate. But we must also not lose sight of the fact that there are decisions to be made to move toward a definitive peace. ETA prisoners have taken this step, but then there have been acts of homage [of terrorists]… I believe that when a sentence has been served, a sentence has been served. We are not going to befriend the terrorists but we cannot be constantly saying that they have not paid a sufficient price. They have paid the price the law says they had to pay.

Q. What should the government do to accelerate the process?

A. There have been no attacks and I am led to believe there is no longer extortion or other means of intimidation. It is true that some satellite groups may have a mistaken idea of this process and there ETA has to perform a pedagogical task. And the abertzale left should speak less of the state as torturer because this offends the victims. There are many steps to be taken, and there are people within the abertzale that can perform these tasks. What is important is that the victims do not feel marginalized and the government is able to take its own steps to ensure that this terminal situation advances definitively. There are weapons to hand over, demobilizations to perform….

Q. What issues are you drawn to or worried about in the political sphere?

A. The lack of communication between politicians. It is a dialogue of the deaf. [Prime Minister Mariano] Rajoy says that [Catalan premier Artur] Mas will not listen, but he is also deaf to subjects that matter to everyone. The justice situation also worries me, especially that victims of Francoism are being forgotten. The politicians display their greatest cynicism when voices like the United Nations tell them: listen, compensate the victims, and they do nothing. I find it incredible that they select victims: some they reward and others they push to the side after they have been asking for justice for 70 years.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.