“Your real parents abandoned you”

The majority of children adopted from overseas suffer racism Most find they have to come to terms with who they are and where they come from alone

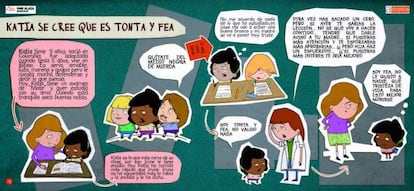

"Your parents abandoned you because you were stupid and they didn’t love you.” “How can you support Atlético Madrid if you’re black?” “Where are you from?” Up to 70 percent of children adopted from overseas by Spanish families say that they have been discriminated against or been the butt of xenophobic or racist comments, according to a survey carried out by Ume Alaia, an association that represents families who have adopted children in the Basque province of Vizcaya.

By the time that they have reached eight, many children have already been told by a classmate that their mother and father are not their “real” parents, says the organization.

Contact between children from different countries is a relatively recent phenomenon in Spain, a country that is still overwhelmingly homogeneous in comparison to other European Union states in the west of Europe (between five percent and 10 percent of pupils are from other countries, according to EU statistics, while in France, the United Kingdom or the Netherlands the figure is double that). International adoption was not regulated in Spain until 1993, and only began to take place toward the end of that decade. Since then, some 50,000 children have been taken in by Spanish families, above all from China, Russia, Colombia and Ethiopia, according to the Health Ministry, most of whom are now approaching adulthood.

María Cardona (who prefers not to use her real name), now 18, knows what it is like to be different. “I was the first overseas child to be adopted in Spain, and what’s more, I was Chinese. My parents say that everybody on Ibiza wanted to see me.”

María was adopted at the age of four, in 1998. “As far as I know, I don’t have any brothers and sisters. People would come up to me and ask who they were, and I would tell them that they were my mummy and daddy, and they would tell me that my parents had abandoned me.”

Laura, who is now 32 and works as a personal assistant to the head of a company, says that the sense of being different never goes away.

By the age of eight, many have been told their mother and father are not “real”

“As soon as you set foot outside your front door, because you are adopted, you cannot be anonymous. Everybody knows that those people you are with are not you biological parents, and you stand out. When you are aged eight, you don’t care, because the only thing you’re interested in is playing; but by the age of 11, you feel a bit strange, and by the time you reach 14 you don’t want to go to the movies,” she explains.

Laura’s parents, a Croat and an Austrian, adopted her when she was a small baby, in the Colombian capital of Bogota. She has two younger brothers, still living in Colombia. The experts say that her not wanting to go out in public is a recognition on her part that there are unbridgeable differences between her and other children.

Adolescence is a particularly difficult time for adopted children. A survey by the British Association for Adoption and Fostering on the long-term effects of adoption shows that the hostility many adopted children experience during childhood continues into adult life. Not all those interviewed in the survey (72 women from Hong Kong adopted by British families in the 1960s) see themselves in the same way: half consider themselves Chinese; 19 percent as British; and 15 percent call themselves British-Chinese.

A similar survey carried out in Sweden by a group of universities highlights the way that the degree of rejection or racism exercised by the host society depends on how different you look: the vast majority of Africans say that they have experienced racism, as have around 30 percent of Chinese, and just 11 percent of Latin Americans in that sample.

Adopted children tend to start asking about who they are and where they came from during the first years of middle school, when they are aged between 10 and 12, and their curiosity typically continues until their late teens. Laura, who has been trying to find her biological mother for the last three years, describes her situation as a “constant coming and going of horrible emotions.” Her family moved from Austria to Madrid when she was 10.

Laura believes that adoptive parents have a responsibility to tell their children the truth, and to confront any difficulties head on: “They have to explain that people are looking at you because you are black, and not pretend that it is because you are more attractive than the others […] I’m sure that families who do this are acting with the best intentions, but the really important thing here is for them not to deny that the child is different.” She says that the best thing parents can do is to strengthen children’s self-esteem, for example by forming friendships with people from the same region or country as their adopted charges. “The people that the parents form friendships with, especially if they are different, become important figures in the child’s life. Nothing makes an adopted child feel more proud than to know that his or her parents have friends like them.”

Psychologist Óscar Pérez-Muga, co-author of ¿Todo niño viene con un pan bajo el brazo? (Or, Are all children born with a silver spoon in their mouth?) says that at the two extremes are children who know about their origins and those that have no information at all about their early years or whether they have any living relatives. Somewhere in the middle, a large number of children experience what he calls “partial reparation,” in other words they know that they have been abandoned, but are aware that they have also been given protection and human warmth. A fourth group is made up of those young people or adults that have been to find out about their past, but who are more confused than ever because so much of the information seems contradictory.

Laura says that she has stopped digging into her past for the moment for fear of finding things out that she may not be able to deal with. The NGO La Voz de los Adoptados (The Voice of the Adopted) says that Spain is woefully lacking in programs or specialists able to help adopted children come to terms with their origins. Pérez-Muga says that the social networks have made it easier than ever to dig into the past about one’s origins, but that doing so without prior preparation or the help of a mediator can be very dangerous.

As soon as you set foot outside your front door, you can’t be anonymous”

“I had my mother’s name and her identity card number, but I had to find out on my own that she was still alive and that she was still living in Colombia. My dream now is to go to meet her at Easter: my big fear now is that she will disappear first,” says Laura. She also knows that she has siblings, but is unsure whether she wants to meet them. “The person I was talking to seems to be putting me off. They only reply to my mails every couple of months. I don’t know who to turn to,” she says.

María Cardona says that she is still in touch with three friends she knew at the orphanage in China, although she has forgotten her time there. The three arrived together in 1998. They live in different cities, but have kept in touch over the years. But in Ibiza, she knows no adult Chinese. “Apart from my Chinese teacher, I don’t know any Chinese people, only the people who run the convenience stores,” she says. She is also unsure as to whether she wants to go to China. “I think that I was abandoned. I don’t know anything else. Some of my friends remember things, and others remember nothing. The orphanages don’t have much information about our families either. I have forgotten everything from that time, which makes me suspect that we may have suffered some kind of abuse. Of my friends, the only one who remembers anything, the oldest, hates everything to do with China. She hates the Chinese, if you like,” explains María. Others, says Laura, have “mythologized their background,” and need to go to their parents’ countries to see it and experience it first-hand.

Ricard Domingo, who has an adopted child from Ethiopia, and is president of AFNE, a Catalan-based association that represents children from the East African country, says that it is important for children to “return to their birthplace.” He has worked with some 20 families that have adopted Ethiopian children, and says that the process can be “tough” but that if a trip is made before children reach adolescence, it helps them avoid many identity problems. “If families cannot afford to pay for such a trip, then at the very least, we recommend them to gather as much information about their adopted child’s country of origin as possible and to share it with them.”

“It can be through the language, food or music, but creating a link is fundamental in helping adopted children come to terms with who they are and to be able to build an identity. At that age, anything that sets you apart from the others can provoke an identity crisis. That is why, for example, adolescents often dress the same. It is very unsettling for them to be asked where they are from and not to be able to answer, or to not know anything about the country where they were born,” says Domingo.

Cristina Negre, a psychotherapist who specializes in adoption, says that the ostracism many children adopted from other countries experience at school is not necessarily is ill- intentioned: “Children resort to discrimination as part of the process of constructing their identity, by comparing themselves and others with the group.”

The important thing is for parents not to deny that the child is different”

The main difference between the racism adopted children and the children of immigrants suffer is that the latter have cultural references at home, along with a protective environment. “Immigrants believe that their families understand them, and that they face the same discrimination as part of the adaptation process,” says psychologist Alberto Rodríguez, who co-wrote the Ume Alaia report.

“Adopted people need to come to terms with the fact that there will be unanswered questions throughout our lives; otherwise, you will always think that people are whispering about you behind your back. Your biological parents can give you the tools, but white people have never experienced this kind of discrimination,” says Laura. “To begin with, you tell them about it, but later on you realize that you are only bothering them, and you end up keeping your feelings to yourself.”

“We hear insults about black people every day,” says Javier Álvarez-Osorio, who has adopted two African children and is the president of the Association of Adoptive Families in Castilla y León. “People don’t want to admit it, but if you sit down and talk to them, you realize that you don’t have to scratch very deep to find racism, and it is much more widespread than you would think.”

Not many studies have been published about the racism that adopted children from overseas suffer, but a study carried out in 2010 by the University of Barcelona, shows that 75.4 percent of adoptive parents say that their charges do not think about their biological family, suggesting that many adopted children feel that their parents do not understand them. The experts say that the need to know where we come from is widespread, and far from limited to those who have been adopted in childhood.

It can be tough but a trip to the country of origin can prevent identity problems”

Montse Lapastora, a clinical psychologist who specializes in adoption, insists that there is a big difference between the rejection that a child who wears glasses or is obese might feel, and the alienation that adopted children can be made to experience, which addresses deeper identity issues.

“I had a Chinese patient who wanted to tear her eyes out, and another, from India, who had dark skin, and wanted to undergo treatment to make herself whiter. Others, from Africa, used to scrub themselves when they were children to see if they could change their color,” she says.

“Anybody who was an outsider, Gypsies, blacks, foreigners… they were all my friends. When my classmates used to go out clubbing, I would go to bars that played funk. My brother went through a phase when all his friends were Latinos,” says Laura. María says that one of her best friends when she first started high school was a boy from Ecuador.

To the feeling of abandonment, many adopted children must also live with the knowledge that they are different. “Around the age of six or seven, children begin to be aware that they are individuals, that they are different. This is a process that must begin early if they are to learn to deal with being different to most other children, but by the time they reach adolescence, and are looking to establish relationships with people who share similar physical characteristics, they realize that they are white, but are trapped in a black body,” says Cristina Negre, who says that many children born abroad but brought up in Spanish families have no way to establish links to their country of origin.

“I have friends that have actually told me that I am lucky not to appear to be Colombian. And this prompts many questions: why? Is it wrong to look Colombian? And what about if you are Colombian? Are people who look Colombian bad? And what would happen if I were Colombian?” asks Laura.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.