“Silence is relegated to religion”

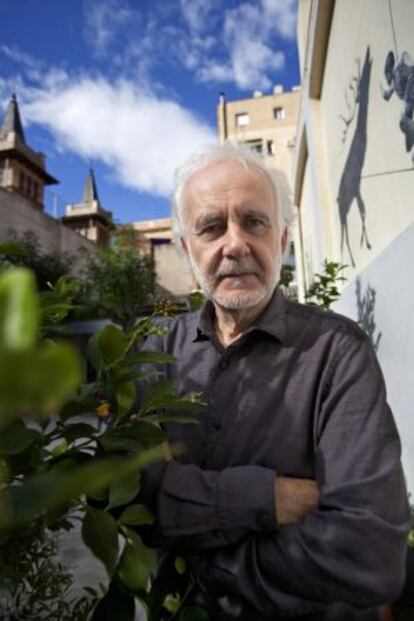

Essayist Ramón Andrés fine-tunes his eclectic themes in a Barcelona convent

Ramón Andrés's workspace is fitting for someone who makes silence one of the pillars of his oeuvre. The owner of one of the most unique voices among Spain's contemporary essayists sits inside a cell at a former convent-turned-artist-center in Barcelona's Gràcia neighborhood. It is here that he chips away at such ambitious tasks as his recently published Diccionario de música, mitología, magia y religión (or, Dictionary of music, mythology, magic and religion), a 1,750-page compendium of cross-disciplinary knowledge, expressed directly and without fanfare - the kind of endeavor that seems impossible for one man to achieve alone.

Every morning at daybreak, the 58-year-old writer, poet and creator of aphorisms cleans the community courtyard, a peaceful spot where the interview took place. Andrés talks in a slow, precise manner that is as devoid of stridency as his prose. His latest demonstration of brilliance is El luthier de Delft (or, The luthier from Delft), an exploration of music, science and culture during the Dutch Golden Age, with a special focus on Spinoza.

"To me, he was a central philosopher," he explains. "I have studied him a lot, he practically represents an ideal lifestyle. I am tremendously interested in that balance."

The book begins with the contemplation of a painting by Carel Fabritius, "a student of Rembrandt's and one of Vermeer's main references," titled View of Delft with a musical instrument sale stand. The craftsman who absentmindedly waits for a client to show up is the cue that allows Andrés to reflect on matters such as the art and science of the era, or on the nature of work itself. "Back then it was associated with the notion of a trade, something one learns with a goal in mind. But these days it is only seen as the opposite of unemployment," he notes.

Knowledge should be alive, since it is an argument against death"

With eclectic aplomb, the author jumps from compositions by Dutch composer Sweelinck to advances in optics, from the relation between the perfection of musical instruments and a flourishing overseas trade, which provided the best woods, not forgetting the role of women and Jews in all of this. It is a tale of erudition, even though the author is wary of those who fly that flag. "I am not convinced by the figure of the learned person; he is like an entomologist pricking at his knowledge with a pin. And I think that knowledge should be alive, since it is an argument against death." Andrés, who is often and erroneously mistaken for a musicologist, began writing essays after nearly 10 years as a professional singer of medieval and Renaissance music.

"Traveling was not my thing," he says by way of explanation. "I am rather sedentary." He might also define himself as a firm believer in the benefits of silence, at a time when noise has come to define the information overdose that assaults us every day. Andrés dedicated one of his more fine-tuned works, No sufrir compañía (or, To not suffer company), to the concept of silence.

"Silence is an inner issue, a mental state. The problem is that silence is not productive, and it raises questions. That is why it is not encouraged. Lay society has not managed to create spaces of silence; we make too much noise. Silence has been relegated to religious moments, to sacred things. And it shouldn't be so. That is another defeat for civil society."

A native of Pamplona, Andrés arrived in Barcelona three decades ago, but he still seeks the refuge of the valleys of Navarre when he wants to work. The Catalan capital, once a cultural and societal hotbed, now seems like a place on the run, which wishes to be something else. And the contemplation of this phenomenon and other current events in Spain has made Andrés somewhat pessimistic.

"Enough of the deception. It seems to me that the world we live in is the result of a giant confusion, a tremendous misunderstanding on everyone's part. I used to think that we were in the hands of madmen, but now I am convinced that we are governed by very vulgar people. There is no solution to Spain. It is a country of brutality."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.