Prepare to meet thy Maker Movement

A global network of small-scale artisans, combining cutting-edge technology with design, is attracting followers in Madrid

The day is fast coming when we will no longer need to buy phones. All anybody wanting the latest generation cellphone will have to do is drop in on the corner shop to print themselves one up: a couple of hours, and hey presto - as simple as handing over the design and having access to a 3D printer and a member of the local branch of the fast-growing Maker Movement.

The Maker Movement started in the United States, and is about using new technologies to, well, make things by combining them with more traditional skills such as woodworking, engineering and metalworking. The approach is now making its presence felt in Madrid, with the appearance each month of a new workshop, coworking space or design studio in what its enthusiastic proponents are calling the third industrial revolution.

A couple of blocks south of Atocha railway station, in front of the Palos de la Frontera Metro stop is Makespace Madrid. The interior is like something out of Star Wars, with cables, unfamiliar-looking machines connected to computers, microprocessors and boards scattered around the place. The founders, Sara Alvarellos, David Rodríguez, Ricardo Merino, Gabriel Herrero-Beaumont and César García, have been in business for just a couple of months, and are confident that they can meet the needs of small businesses and the general public.

Maker culture is based on a principle: to share knowledge freely without patents

For anybody unfamiliar with computers, everything spoken between these four walls will sound like Greek: Arduino, CNC, free software and hardware, 3D, laser... But maker culture is based on a fundamental principle: to share knowledge freely without patents. It has been described as the Do It Yourself of the 21st century. For example, any maker worth their salt uses Arduino, an open-source hardware platform based on programming language. That's to say, a device that just about anybody can use and that is connected to the physical world via the virtual world. "Thanks to shared knowledge we can build just about anything, so let's stop being a service-oriented economy in Spain and start being producers!" says Alvarellos.

Makespace Madrid already has around 70 partners, but hopes to bring together around 200, a figure that would make the enterprise sustainable, so it wouldn't have to rely on either subsidies or private capital. "As a rule, they are industrial designers, engineers and people who understand machines and how they work," explains Alvarellos, while at the same time emphasizing that there is also room for artists, scientists, and even doctors in the Maker Movement. "It will take some time to get up and running, but we'll get there," she says confidently.

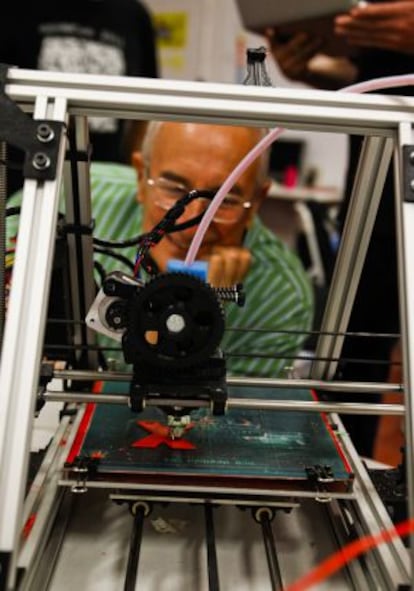

Juan González, who has a Ph.D in robotics, agrees that the Maker Movement is here to stay, and is no passing fad. "I am convinced that this is the future," says the creator of the Clone Wars project, a community of more than 1,500 members that offers practical advice on how to build 3D printers by using open source programming. González, better known to his friends as Obijuan, in homage to the Star Wars character known for his wisdom, says that makers build because this is their way to understand the world they live in.

Movers and makers in Madrid

- Makespace Madrid. This group develops creative projects and prototypes at Calle Pedro Unanúe, 16.

- MADfab. A free hardware and digital manufacturing space located at Calle Canillas, 13.

- Los hacedores. This digital workshop-cum-school is to be found at Calle Bárbara de Braganza, 4.

- Estudio Buenos Días. A group of designers and artists with their own laser cutter. Calle Molino de Viento, 30.

"We are campaigners, in a way, for the right to knowledge, the right to be able to access the knowledge that makes our world. We want to be able to see inside the machines, to touch them and to change them if we want." What's more, González says it is no longer necessary to be able to speak English to be part of the technological world: "All this stuff is available in Spanish now, so there is no reason for people in this country not to get involved."

Clone Wars is not so much about making things as building new, better and cheaper 3D printers. "We want people to build their own tools and their own models. I have four at home, but that's pretty unusual," says González, who insists that for him, the important thing is not about making something that looks nice, but something that works.

The philosophy at Estudio Buenos Días is very different. This tastefully decorated coworking space tucked away in a tiny ground floor office in the newly fashionable area north of the Gran Vía that has come to be known as Triball is home to six artists and designers who apply the new technologies to the traditional arts and crafts.

"We are artisans and we like to make useful things that are also nice looking," says 25-year-old Jaime Martín, who set the space up.

Álex Fábregas, a dyed-in-the-wool maker, and Martín's partner, describes a three-stage working process: the idea; looking for personalized products; and then using the tools to make them.

Let's stop being a service-oriented economy and start being producers!"

"A maker is somebody who designs and makes their own products using technology," he explains, adding that knowledge is global, and production local.

Martín and Fábregas are the only people in the center of Madrid with their own laser cutter. The machine looks distinctly 20th century, as is the technology that makes it work, but this is one of the latest models, and works like a dream. It will cut wood and plastic, and is capable of turning pretty much any idea into a working reality. "In just a few moments you can create the pieces required to make a speaker, a bicycle or a lamp," explains Martín, pointing out that such cutters are rapidly falling in price, and can now be bought for little more than a thousand euros. Members of Madrid's Maker Movement believe that the current economic model is finished. "It's time for a change," says Adam Jorquera, the founder, along with Javier Gordillo, of Los Hacedores, the capital's only school dedicated exclusively to teaching the skills required to build things using 3D technology. "The production line process created by Henry Ford will eventually disappear, thanks to 3D printers," Jorquera argues.

The pair are almost evangelistic about spreading the 3D message, and decided to give up their jobs to join the movement and teach others. "People are amazed at what these machines can do, but you have to learn how to use them," says Jorquera, adding: "This is the first time in history that it has been possible to turn a complex design or idea into reality in just a few hours," he says.

Gordillo and Jorquera say they can empower just about anybody with the skills needed to operate 3D printers and other high-technology machines using simple programming. "Our next goal is to get schools involved in this: to get kids to pick up from an early age how to use these toys that so fascinate us," says Gordillo. They currently run workshops for young people.

Gustavo Ferrari and Juan Pascual have worked in electronics all their lives: Ferrari helped to build the first 3D Clone Wars printer. He points out that open-source coding has its roots in the plans that appeared in the build-it-yourself practical electronics magazines of the 1950s. "The only difference is that in those days you had to be able to understand English. The internet has obviously also made the whole process much easier."

The pair run MADfab, which unlike the majority of Maker Movement operations, is a privately run enterprise. From their tiny premises in the north of the capital they make analogue radios using digital technology.

"It's our way of making ourselves known: making something old out of technology. We are makers but we have been doing it for 30 years now," says Ferrari.

The Maker Movement is now a global reality, and its acolytes believe that within a few years, anybody who wants one will have their own 3D printer at home, after all: back in the 1980s, who would have thought that every household would have a computer?

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.