The Guerrilla Girls fight on

A retrospective in Bilbao brings together the work of this female collective, which has been campaigning against sexism in the art world since the 1980s

One morning during the Reagan era, buses in New York City were seen carrying bright yellow billboards informing passersby that less than five percent of the work on display in the Metropolitan Museum's modern art sections was made by women, while 85 percent of the nudes hanging from the walls were female. A copy of Ingres' famous nude Grande Odalisque, wearing an incongruous gorilla mask (the group's symbol), asked itself: "Do women have to be naked in order to get into the Met museum?"

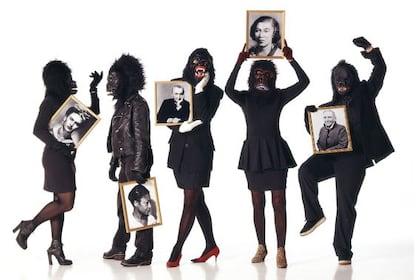

That skirmish with one of the sanctuaries of culture was a milestone for the Guerrilla Girls, a group of feminist artists that was founded in New York in 1985 to protest against sexist and racist discrimination at art galleries and museums. Wearing gorilla masks at all public events, flaunting their feminist status and using urban guerrilla tactics, they soon began chalking up the scandals. Their working tools were high heels, paintbrushes, posters, strategic espionage and, above all, razor-sharp sarcasm. It was as underground as it gets. In the midst of a conservative counter-revolution, the Guerrilla Girls managed to draw attention to inequality in art using an explosive combination of cheek, humor and figures. You could attack their members, but their statistics were untouchable.

Some of the "advantages" of being a female artist, they said ironically, included being able to work without the pressure of success; being certain that one's art is always going to be described as feminine; being able to choose between a career or motherhood; and not having to deal with the embarrassment of being called a genius.

Their entire artillery, from the group's foundation to present times, is now on display at Bilbao's La Alhóndiga center, which last week inaugurated the first retrospective focusing on a collective that has attracted 50 or so members over the years, and whose work already hangs in museums.

The visit provides a good opportunity to see how much has changed in the art world in the last three decades. "Things have changed a lot, but I couldn't say whether for better or for worse," says one of the two anonymous members of Guerrilla Girls who came to the opening, and who goes by the nom de guerre of Frida Kahlo. "The good thing is that museums and galleries can no longer leave out female artists or artists of color, but at the same time there are new forms of discrimination. There is a glass ceiling in art: there are many women curators, but not many directors, and artists can only get so far. And then there is the crux of the matter: women make a tenth of the money that male artists make."

Both she and the artist who goes by the name of Käthe Kollwitz, who also traveled to Bilbao, belong to the group of founders — there are fewer than a dozen of them — and have successful careers as individual artists. "You can't change everything at once, but we are doing something that we believe in, in our own slightly crazy and creative way," says Kollwitz. "The mask is what a feminist has to wear in the world of art in order to be taken seriously."

Knowing the real names behind the masks has always been a popular demand, and so on one occasion the Guerrilla Girls announced their real identities — despite concealing them among a list of 500 artists. For another campaign, they recruited colleagues such as Richard Serra, John Baldessari, Sol Lewitt and Alex Katz in an effort to get gallery owners to show more work by women and black artists.

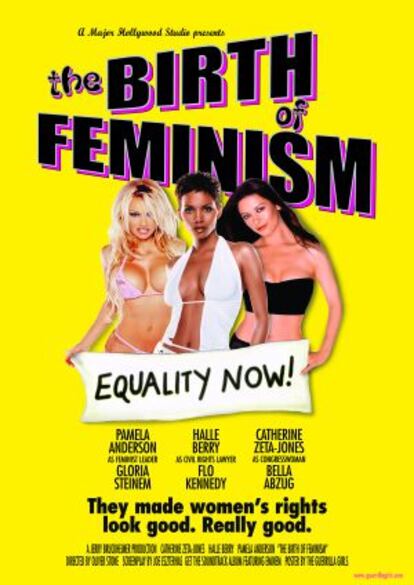

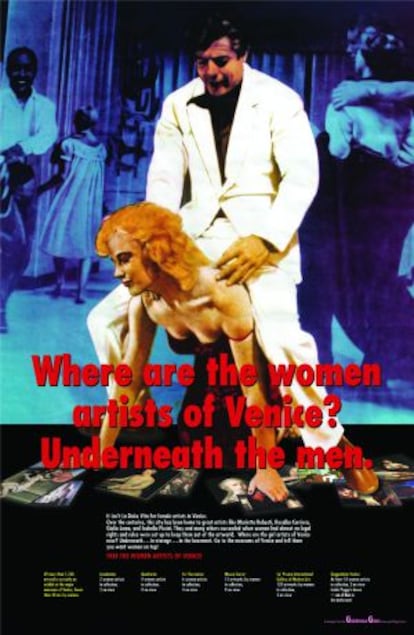

In 2000, the campaigns began to reach out to the movie industry. One of them claimed that "even the US Senate is more progressive than Hollywood" (14 percent of senators are female versus four percent of film directors). The group also looked beyond the US borders, showing up at the 2005 Venice Biennale with ironic posters congratulating the city's historic museums for having paintings by women in their holdings — albeit locked away in the basement. "Of the more than 1,238 artworks currently on display at the major museums of Venice, fewer than 40 are by women," read the poster. In 2009 they made a piece for Montreal in memory of an anti-feminist murder at École Polytechnique, an engineering school. Their campaign took issue with sexist remarks made by famous thinkers and artists throughout history: "One hundred women are not worth a single testicle," (Confucius); "Nature intended women to be our slaves. They are our property," (Napoleon); "There are only two types of women: goddesses and doormats," (Picasso).

"We're bothered that it has always been OK to make denigrating public statements about women, and shocked by the violence and abuse this language continues to provoke," they said about that project.

For better or for worse, the Guerrilla Girls' work leaves nobody unmoved, judging by some of the messages they have received over the years: "As a woman I am tired of your stupid, lesbic feminazism," or: "Dear Guerrilla Girls: I work for Tony S. He's on one of your posters. You're right. He's an asshole. Here's $25. Keep up the good work."

Guerrilla Girls 1985-2013 . Until January 6, 2014 at Alhóndiga de Bilbao, Plaza Arriquibar 4, Bilbao. www.alhondigabilbao.com

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.