Up against a brick wall

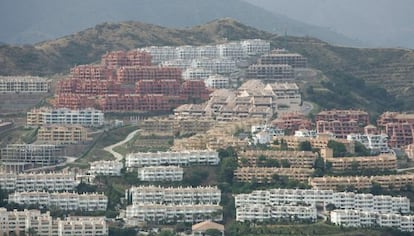

During Spain's decade-long property boom, thousands of buildings were illegally constructed in protected areas Getting them demolished is proving a challenge

Five years after Spain's construction bubble spectacularly burst, the Environment Ministry says that it is facing "serious problems" when it comes to demolishing thousands of buildings throughout the country that contravene planning laws, but that were given the green light by local councils often in cahoots with property developers.

The ministry says owners of condemned properties are using delaying tactics to put off the arrival of the wrecking ball for as long as possible, hiring lawyers to pursue every approach, to look for loopholes or to try to take advantage of legislative changes, such as the recent amendments to the law on properties built close to coastal areas. Cash-strapped city halls and local councils, whose job it was to apply town-planning rules in the first place, say that they now lack the funds to pursue lengthy court cases. "We are up against a brick wall here," says Patricia Navarro of Cádiz City Hall's environment department.

The Environment Ministry's report on the extent of illegal construction in Spain for 2012 highlights a "paradoxical" situation whereby appeals against demolition orders are handled by local and provincial courts that do not share the same criteria in assessing them.

Legal chicanery

When it comes to stopping a demolition order from going ahead, the courts have discovered that people will go to just about any lengths. In the four years that on average it takes to carry out a demolition order, officials say that they have come upon a wide range of ruses, from the case of an illegally constructed property on agricultural land that the owner said was the offices of his bee-keeping business, to more complex scams such as faking photographs to make it look as though a building had been knocked down.

"We have come across the weirdest situations," explains activist Ángeles Nieto, from Ecologists in Action. "There are developers who ignore an order to stop construction, so that when we move in to demolish it, the building looks nothing like the description when the sentence was issued."

In Colmenar Viejo, a village some 40 kilometers to the northwest of Madrid that has become a dormitory town for the capital, an architect who had built a property on protected land dressed up as a bee-keeper at court hearings, says Juan Manuel López, a lawyer working for an association to defend the local area. The architect had chosen a spectacular spot, amid an area set aside for the protection of imperial eagles. The 200-square meter property was closed off on three occasions.

"He tried to argue that the building belonged to a company set up in his wife's name, and that because of the complaint made about its illegal construction, he had been expelled from the company and was no longer responsible for it," says López.

After further lengthy arguing, the environmentalist group managed to get the court to put a claim in for the regional government of Madrid to cover the cost of demolition. "We really had to fight this one out: the defense kept coming up with delaying tactics, requiring us to say how much of the building needed to be knocked down; the impression in court was that the defendant's word counted for more than what the judge was saying," López says.

In nearby Guadalix de la Sierra, it took eight years to get an illegally built property demolished, but in the last three years, López and his colleagues have managed to get seven other properties razed to the ground. "Some of the owners saw that we were serious about this, and decided to demolish the buildings themselves, thus saving the court costs and a stiffer fine," he says.

On another occasion, in Garganta de los Montes, also nearby, the owner of an illegally built house in a specially protected area had painted it green in a bid to avoid detection. In Pontevedra, Galicia, the owner of an illegally built property presented photographs purporting to show that it had been demolished to the court overseeing the case. "It was a fake," say sources at the local environmental office.

A similar case recently came up in Madrid, where documentation had been faked in an attempt to show that a property had been demolished.

Javier Leiva, a member of the association set up by the owners of properties due to be knocked down in Mijas, Málaga, says that fighting to save his home has come at a personal price, setting aside the legal costs. "There are a lot of people here suffering from depression and stress," he says.

His home is built on land zoned as rural, as are many others. He says that he believes in the end the houses will be approved. "You would go to the town hall, which in those days was run by the Socialists, and they would tell you that yours was borderline, but not that they would knock the place down," he says.

Leiva says that all his taxes and other contributions on the property are up to date, and that his property figures on his tax declaration. But the building is not on the list of the 4,000 of the community's 8,000 illegally built homes that will be spared. In 2008, the local council began to issue fines amounting to 10 percent of the value of the property on people who had not carried out the demolition order.

At that point, some 2,000 homes were slated for demolition. "Other ways to deal with the paperwork" were discovered and the fines stopped. Things are calmer now in Mijas, but the court orders are still waiting to be carried out. "Any day now, the council could just turn up here and knock my house down," says Leiva.

The problem is further exacerbated because the State Prosecutor's Office has no exact figures on how many demolition orders have been issued. Neither is there any census on how many buildings there are in Spain that do not meet planning requirements. But the majority of them will be in Andalusia, where the regional government estimates around 300,000 — in Málaga alone there are 60,000. Meanwhile, Greenpeace says there are at least 50,000 houses along the coast in Valencia that are lacking the necessary permits or that contravene zoning laws. And in Cantabria, where building rules were regularly flouted during the construction boom, there are currently 663 demolition orders waiting to be carried out, says the regional government.

It is hard to make sense of the reasons given by provincial courts when hearing appeals against demolition orders. In Seville, one court official described an "irreconcilable disparity" in the number of court cases. While three judges in the provincial court tend to carry out orders "reasonably frequently," another "doesn't, as a rule," apply them, says a source there. In some cases, the owner of a building has been sent to prison for refusing to accept civil responsibility for the demolition; i.e. that they must pay for it.

Jaén, in the interior of Andalusia, stands out for the "extraordinary reticence" of its judges to carry out demolition orders. Of the 72 rulings against zoning infractions, only two have so far been carried out. One of the most flagrant cases of impunity is a housing development built close to the Puente Tablas archeological site, in an area of the city declared an Asset of Cultural Interest. The neighborhood is littered with illegally built houses; demolition orders have been issued for some, but not for others. The owners of those waiting to be knocked down accuse the local authorities of "judicial insecurity" and are doing everything possible to delay proceedings.

In Cáceres, the prosecutor's office complains that some judges have displayed a lack of "the most basic knowledge of judicial procedure" regarding demolition orders, while in Valencia, prosecutors say that the courts no longer systematically apply demolition orders, or routinely appeal against carrying them through. While the demolition orders may be piling up, the good news is that they are being approved with greater frequency: in 2011 the figure was 37 percent; in 2012 it rose to 63 percent.

Last year, the Supreme Court attempted to provide some clarity, issuing a ruling in June recognizing the main arguments of the State Prosecutor's Office on the need to carry out demolition orders, saying that this was the only way to repair the damage caused by the offense. "Demolition is a civil responsibility issue," says Antonio Verger, the Environment Ministry's coordinating prosecutor.

State prosecutor Patricia Navarro asked the Supreme Court to clarify its position by lodging an appeal regarding an illegally constructed building in the upscale Puerto de Santa María yacht marina in Cádiz that had still not been carried out. The Supreme Court accepted that demolition in such cases should be the "general rule" and not the exception, a decision that has set a precedent and is reflected in Article 319 of the Penal Code.

There are some 40,000 properties in Cádiz that lack the necessary paperwork; at the end of 2012, there were just 70 demolition orders waiting to be executed. "In Chiclana, Chipiona, or anywhere along the coast, there has been rapid growth: the presence of an illegally built property tells other people they can do the same," says Navarro. She says that she has demolition orders on her desk dating back to 2007 due to legal chicanery.

"People will file for a pardon, which is just not applicable in these kinds of cases, because we are not dealing with a sentence," she says. Owners of illegally built property are now hoping that they can use the national Coastal Law, which was amended this summer to reduce the number and extent of protected areas along the country's coastline. They may also hope to benefit from the decree issued earlier this year by the regional government of Andalusia regularizing 90 percent of properties without the required permits; there are also plans in many towns and cities to simply change local legislation.

In the Valle del Almanzora, in inland Almería, the largely foreign owners of some 12,000 properties built illegally have lodged a collective appeal with the European Court of Human Rights against a demolition order. For the moment, the judge in Almeria's provincial court has suspended the demolition of one of the properties, owned by a British couple, until Strasbourg has reviewed the case. Gerardo Vázquez, the group's lawyer, says that changes need to be made to Spain's land laws, and that building procedures need to be simplified. "The procedures are Byzantine, and it's clear from the number of properties built that the law has been interpreted freely," he says.

"Many of these are homes purchased in good faith in the period from 2000-2006 when the valley witnessed an uncontrolled construction boom. Today many are without mains water and electricity; many more have dubious electricity connections and lack a final habitation certificate," reads the group's website.

Further down the coast, in Mijas, Málaga, there are some 8,000 illegally built properties. The regional government's recent decree offers hope that around half will be given a reprieve. The owners of the remainder are desperately looking for legal loopholes. Several properties have already been demolished in the community, and the Popular Party-controlled local council says that there is nothing it can do to stave off further orders.

Meanwhile, in Navarre, just five demolitions have been carried out, which have also involved freezing the accounts of the owners to cover the costs. Like many other areas in Spain, owners of agricultural buildings on farm land in areas close to towns have gradually extended them into full-size homes. The typical procedure has been for the local council to issue a fine and then, on a fait accompli basis, approve the construction.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.