Have road crash victims become just another statistic?

As the death toll on Spain's highways comes down, families of those killed feel neglected

Road crash victims feel they are nothing more than a number without a face - a cold statistic that no longer makes society feel a single pang of distress.

"We don't have a name because we don't all die together," they claim. While Spain shuddered at news of the recent train accident near Santiago de Compostela, which killed 79 people, or at the 2008 Spanair plane crash that resulted in 154 fatalities, this summer's 239 road deaths are being described in positive terms. This, says the association Stop Accidentes, is because the death toll is gradually going down, as fewer people die in car accidents each year.

"But the grief of all victims is equally intense, and their problems equally severe," says Paco Canes, president of the State Association of Accident Victims (DIA).

The Cabinet recently approved regulations that will offer comprehensive support to the victims of air crashes; just days later, when the Santiago train derailed, this support was also extended in the case of railway accidents. But not road accidents - people involved in the latter only have a Victims Attention Unit to turn to. Created by the state traffic authority, it keeps offices in all provinces, but its role is merely to provide information.

Although associations consider it an important first step, they demand a protocol that will help provide guidance to families in the first moments after an accident. "If you don't know where to find victims units or associations, it's as though they don't exist," says Canes, adding that something as simple as a brochure at hospitals, courthouses, police precincts and funeral homes would solve a lot of problems.

Ana Novella, president of Stop Accidentes, goes further and argues that there is the need for a secretary of state's office to assist victims of any type of accident.

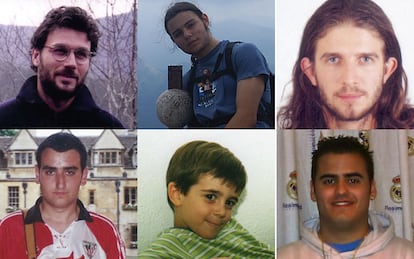

From the year 2000 to September 1 of this year, road collisions resulted in at least 51,453 deaths, which is as many as the population of Cuenca or Ávila. Another 251,046 people were seriously injured. The following are the stories of seven road accident victims and their families.

JOSÉ MANUEL, 23. "It's the price to pay for progress"

"My son was killed on the road," says Charo. José Manuel was 23 when an articulated truck from the milk company Leche Pascual skidded out of control. "It jack-knifed and took four cars with it." Three people died, including Charo's son and his friend, who was in the passenger seat. "That boy was in a coma for three years and ultimately died, but the insurance company pressured his mother into dropping the criminal charges in exchange for paying for his treatment," she recalls. Charo did not drop the charges, although it was seven-and-a-half years before the trial took place. The truck driver "lacked expertise" and was going over the speed limit, says Charo, who is demanding that transportation companies hire drivers with better training. But the court did not take the expert report into account, and the man who was responsible for her son's death was sentenced to pay a daily 10-euro fine for a month - a total of 300 euros. "The worst part is seeing society accept accidents that could have been prevented," she adds. The insurance company told her that it was "the price to pay for progress."

SANTIAGO, 33. "His belongings were in the car pound"

Jeanne's son "inaugurated the 21st century." "Santi died on January 1, 2000 in what was nearly a head-on collision" while he was returning home from a New Year's Eve party, says Jeanne, who is one of the founders of Stop Accidentes. "The first thing they told me was that it was his fault," she explains. Yet blood tests showed that he had drunk nothing but coffee. "How can they say something like that without even reading the police statement first?" she asks. Those initial comments, she says, "are the ones that hurt the most, and they remain imprinted in your memory forever." At first she was incapable of thinking clearly, but 15 days later Jeanne realized that nobody had given her son's car keys back. The Civil Guard told her to go to the pound. That is where her sister-in-law found the keys, still in the ignition. Santi's jacket was still in the car, too. "Why weren't they more careful?" she asks.

PABLO, 4. "The judge told us we were making him nervous"

On October 27, 2001 an underage driver was clocked doing 95km/h on a Valencia street with a speed limit of 50; he ran through several red lights, lost control of his vehicle and skidded on to the sidewalk, killing four-year-old Pablo. "It happened right beneath my house," says Ana Novella. Her other son, who witnessed the accident, gave her the news. "At that initial moment they give you a sedative to calm you down, then they send you home, and that's it," she explains.

It was four years before the trial was held. "My husband and I would take turns to go to court and see how the case was going, until our lawyer told us that the judge had asked that we stop going so often - it was making him nervous," says Ana indignantly. So they started going every day.

According to the president of Stop Accidentes, some victim support offices run by the Justice Ministry are starting to assist road accident victims. "But there are still lots of places where they are either not operational or people don't know they're there," she explains. "When you lose a child, you're walking around like a zombie, and could use some guidance."

YASSER, 25. "When they're young, it's like they're looking to get killed"

Rosa cannot forget the face of the forensic expert who would not let her hug her dead son. "I neither forgive nor forget," she says. Yasser was 25 when he crashed into an all-terrain vehicle. "We don't know what happened, but I always think that I lost my son and that at least he didn't take anyone down with him, because I could not live with something like that weighing on my conscience," says Rosa very serenely.

"There is nothing quite as cold or horrible as the aftermath of an accident," she recalls. "And when the victim is young, it's even worse. Nobody listens to you, it's as if they think that they were out looking to get killed. But what young man full of life is going to go out seeking his own death?" she asks. According to Rosa, "the relatives of young victims get the worst treatment, when perhaps they are the ones who have the worst time of it because their children had their whole lives ahead of them." Rosa was unable to get back her son's CDs or the sports bag he had in the car.

"I wanted to keep his soccer uniform, but the tow truck people tell you that the ambulance people took it away, and the ambulance people tell you to go ask the tow truck people," says Yasser's mother, who never did find out what happened to her son's belongings.

JONATHAN, 17. "The ambulance didn't come - they thought it was a joke"

Jonathan Blanco had left the house at 8am on January 8, 2001 to take a bus to school in Castro Urdiales (Cantabria). "A female driver slammed into him, sending him flying for 60 meters, and then she drove off," says his mother, Maribel. It took them an hour to locate him, but the emergency services would not come out until the body was found. By then he was already dead. "They thought it was a joke," she explains, because it was the day that school was starting again after the Christmas holidays.

The impact was so hard that the car that hit him broke down "three or four kilometers later." The driver - who is the daughter of a Socialist politician - returned to the scene of the accident with her family. "When I found out it was her I asked her why she didn't stop, but she didn't even apologize: she just turned around and walked away."

Jonathan's mother says she felt "dead." She had lost a shoe while she searched for her son's body, but it was not until three days later that she noticed the splinters that had lodged in her foot.

Her lawyer "left me in the lurch on the day of the trial." And the court proceedings only increased the pain. According to Maribel, the police report said the driver admitted that she was very familiar with the spot where she hit Jonathan, yet the judge ruled that "she could not foresee someone being there." The court did not take into account the fact that it was a hit-and-run, or that a fellow student confirmed on the same day of the accident that Jonathan was already at the bus stop when the accident happened, and not crossing the road, as the defense claimed. "They told us we had manipulated him," says Maribel, who still cannot understand why the court found Jonathan entirely to blame for his own death.

ENAITZ, 17. Sued by the man who hit and killed their son

Rosa's son was hit by a car in 2004 while he was riding his bike. "We were at a campsite in La Rioja, and an Audi A8 sent him flying through the air," his mother explains. There wasn't even a trial because the judge ruled a claim preclusion. "They wrote the report to fit the driver's needs," says Rosa.

Enaitz Iriondo's mother managed to obtain a reconstruction of the accident. The Civil Guard showed that the driver was going over the speed limit and that he hit the teenager when the latter was already on the road, not as he was coming off the entry lane. Although Rosa has appealed to the Constitutional Court and the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, that original ruling has closed all doors. In the meantime, the driver of the Audi A8 sued his victim's parents for the damage to his car.

MIGUEL ÁNGEL, 20. "They didn't test his blood alcohol content"

Miguel Ángel was driving down a road when he found a car stopped right in front of him. When he veered to try to avoid it, he found an all-terrain vehicle right in his path. Nobody ever explained to his mother, Angelines, exactly what happened. What she does know is that the vehicle rammed into his son's car, pushing it into a vertical position. "When it fell back on the ground, the damage to Miguel Ángel's brain was such that it killed him." The judge did not accept that the driver was talking on the phone, even though a list of his calls shows that at the time of the accident he was calling his wife.

Angelines also criticizes the fact that the driver did not get tested for alcohol content in his blood. "And these things keep happening," she warns. "Fifteen days ago, a lady was hit and killed, and the police did not run any tests on the driver."

The stories behind ghost bikes

If, strolling around the streets of Madrid, one were to come across a white bicycle chained to a tree with a small sign next to it, chances are the casual observer would think nothing of it. Perhaps the owner is very protective of his property, and has taken all available precautions to ensure it does not get stolen. But the reality is very different. In recent years, the capital has been joining a movement that has already sprung up in other major world cities: using "ghost bikes" to raise public awareness about cyclist deaths caused by motor vehicles. Right now, there are at least three such bicycles in Madrid.

The idea for the ghost bikes is reported to have originated in St Louis, Missouri in October 2003. It is attributed to Patrick Van Der Tuin, who placed the first white bicycle on Holly Hills Boulevard after witnessing an accident in which a car hit and killed a cyclist on a bicycle lane. The idea caught on and soon there were more than 15 ghost bikes in the city. From there, the practice spread to other US states and other countries.

The first time a ghost bike showed up in Madrid, it was after an accident that took place on March 19, 2010, where Avenida de Andalucía meets Alcocer street, at 9.30pm. The driver of a sedan hit two bikers, killing the youngest one, Matías, aged 17.

The other two bikes are for victims who died much more recently. While the debate was raging over whether cyclists should wear helmets within Madrid city limits - a measure championed by the DGT traffic authority - a 54-year-old Italian man, Mario P., was run over by a National Police patrol car, which was on its way to the Arganzuela precinct. The accident occurred at 10.30pm, and the report stated that the cyclist was wearing no vest, no helmet and no lights on his bicycle, and was crossing the road at the wrong place. There is a white bicycle marking the spot, chained to the fence on Ronda de Toledo.

The last case is, if anything, even more dramatic. Óscar Fernández Pérez, 37, a resident of the northern Madrid neighborhood of Barrio del Pilar, was on his way to work in Cuatro Caminos on August 7 when he was run down by a white Ford Focus. The driver, Mauricio Eduardo Apolo Granda, 26, had already had his driver's license revoked until February 2017. The signs on the road suggested that Granda dragged Fernández and his bike several meters but did not brake; the cyclist was left lying on the curb, badly wounded, until another driver came across him and alerted the emergency services. But Fernández had been dead for some time already. The police arrested Granda that same day, but he refused to make a statement. A judge released him on condition that he show up at court every Monday; his passport was also taken away as he was considered a flight risk.

A white bicycle and a few red candles mark the spot where Fernández was killed. He always moved around on his bike, says his brother José Javier. A group of cyclists headed by the association Bicicrítica paid tribute to him on August 20, after staging a protest in front of the alleged hit-and-run driver's house.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.