A republican in Hassan II’s court

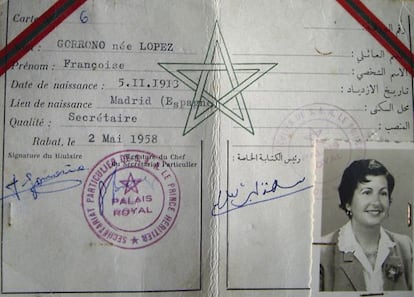

After fleeing Franco's Spain, Paquita Gorroño took refuge in Morocco She ended up working for the future king, but never came round to the idea of monarchy

A little less than a century ago, a woman was born in Madrid whose life would turn out to be long, difficult, and filled with adventure. Born into a wealthy family, Paquita Gorroño was expected to marry, raise a family, and enjoy a comfortable, peaceful life.

But things turned out differently. Today, she is a minor celebrity in the city where she lives, Rabat, the Moroccan capital, and where she expects to spend the days leading up to her 100th birthday. Gorroño insists that she has no wish to return to the country she was forced to leave some 74 years ago, when Franco rose to power. This is the story of an atheist republican who ended up living in a country where the monarchy is sacred, and where the head of state is also the head of the national religion: Islam.

She describes the summer of 1936, when her life changed: "Everything was going absolutely swimmingly. My only concern was where we were going to spend the summer. Against my mother's wishes, I wanted to work. She thought I was crazy, but I decided to apply for a job with Iberia, which was about to open a route between Madrid and Paris and was looking for French-speaking young ladies to work as cabin crew. I spoke French fluently because my parents had sent me to study in Paris. I would have been one of the first hostesses on that route, but the Civil War interrupted everything," she says.

Gorroño fled Madrid after the July uprising, heading first to Valencia, and then to Barcelona. "In 1939, Franco's troops entered the city, and I fled with little more than the clothes I was wearing." While en route to France, a truck loaded with men was attacked several times by fighter planes. The lorry was picking up the wounded, and they ended up in a French concentration camp, Le Boulou. "There were thousands of Spanish soldiers there; the camp was a transit point for other camps. The French soldiers told me that they had been told that the Spanish troops were little more than bandits, communists and anarchists who killed and pillaged wherever they went. But instead they found themselves looking after women, children, and old people. There were no latrines in the camp, and it was chaotic because the French and Spanish didn't speak each other's languages. One day I saw this very long line, and so I asked what it was for. They told me that the French authorities were handing out safe-conduct passes to leave the country. I asked the French authorities where I could go. They said Morocco or Algeria, if I could prove that I had family there."

Gorroño's husband had an uncle in Morocco, and so she decided to write to him. The reply came immediately via telegram, sent by his wife, saying that he had just died. "The French official said that we would be able to use the funeral as a reason to go to Morocco. In return, they asked me to help translate for them. And that's how I got to Morocco."

Now it is the country where she wants to die, but at the time, it was the last place she wanted to be. "I always associated Morocco with tragedy. Next to our house in Madrid, there were barracks where Spanish troops departed for [colonial wars in] Morocco. We used to see the mothers throwing themselves on the ground and hugging their boys to try to stop them from being sent away. The police would have to intervene, and it was impossible not to feel sympathy for those women. My grandmother used to say that it wasn't the Moroccans who were killing our boys; it was the Spanish government. The Moroccans were simply defending their country."

Gorroño found a job as a nanny, and then worked in a cork factory. But when the French surrendered in the summer of 1940, the French authorities ordered women back into the home, and foreigners were not allowed to work. She managed to get by, until one day, a prince came into her life. Through a friend, she found a job in the Royal Palace as a typist.

"I met Prince Hassan when he was 14. The first thing he asked me to do was type some invitations to a party at the Royal Palace. His father, Mohammed V, was very strict, and he made him study during holidays. I felt sorry for him, thinking that my child was on vacation, but that the boy who would become king was working."

When the prince became Hassan II, Gorroño accompanied him to the Spanish exclave of Tétouan to review Franco's troops. "It was a bit surreal, but in every tragedy there is always a comic element."

She was unable to return to Madrid, refusing to have her passport stamped by the military regime now running Spain. "Hassan understood," she says, adding: "When Morocco won its independence, he wanted to merge the two armies, from the north and the south, and he needed somebody bilingual. I reminded him that I was a political exile, which he had always known, and he told me that this was not a problem because his people had nothing to do with Franco."

Mohammed V was very strict, and he made him study during holidays. I felt sorry for him"

Once the merger of the armed forces was carried out, Hassan asked Gorroño if she would like to be his personal secretary. "In the palace, everybody's a spy of one sort or another. When the prince spoke with somebody, there were 50 pairs of ears listening, although they didn't know that they in turn were being listened to."

A few years later, Gorroño grew tired of the atmosphere in the Royal Palace and decided to look for a new job. "There are people who speak badly of Hassan, and they have their reasons, but he was always very kind to me. When I left, he told me that I would always be welcome in his home, and that if I needed anything I just had to ask. I only went back to see him once, many, many years later, when I was threatened with being thrown out of my house. The owner wanted to increase the rent, and even told the court that he needed the apartment for a family member. I called the palace and told them who I was. Five minutes later they called me back, saying that a car was on its way to pick me up. I told the king about the situation, but he must have misunderstood me, because when I was leaving, the man that was escorting me asked how much money I owed. I told him that I didn't owe any money. He then told me that the king had told him to pay my debts. We eventually cleared the matter up, and when I went to court, the owner of my apartment didn't even bother to show up."

Gorroño has remained in the apartment to this day. For the last 12 years, she has been looked after by her Moroccan carer Fátima. She has separated from her husband and is currently single, although she says that there was a time when she considered accepting one of the many marriage proposals she received. Her son now lives in Prague.

Only once has she thought seriously about returning to Spain: "When the Allies won the war, all the exiles in Rabat came out on to the streets to celebrate, waving republican flags. We were convinced that this would be the downfall of Franco. My husband and I even went on holiday, touring Morocco, thinking that we would be leaving forever. But Franco didn't fall. After he died it was clear that Spain wasn't really going to change, and so I never went back. I will die without ever having seen Ávila, which is just 100 kilometers from where I was born."

Gorroño's television is tuned to just two channels: Euronews and Russia Today. Nevertheless, she is well informed about events. "Recently I read that 49 women had been incarcerated in El Salvador for having had abortions," she says, continuing: "I like the fact that a woman is running Germany, even if she is a right-winger... This safari the king went on, it was obviously to shoot elephants, because it's the biggest animal out there, and so he knew he couldn't miss."

Asked about the heir to the Spanish throne, Prince Felipe, her reply is simple: "He's very tall."

Gorroño has been living in Morocco for 74 years now, but has not been won over by the monarchy. With a laugh, she says, "They used to call me La Pasionaria of Rabat."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.