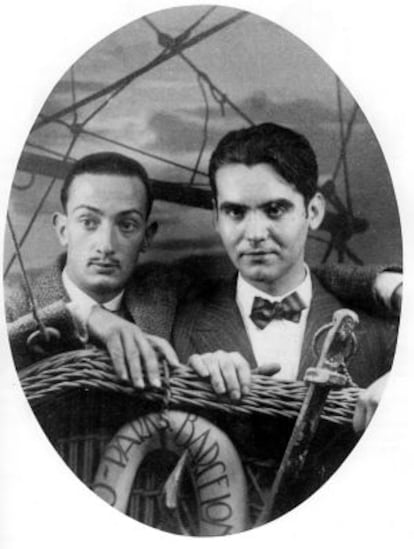

Dalí and Lorca’s games of seduction

'Querido Salvador, Querido Lorquito' is a new book compiling the passionate correspondence between the two young geniuses from 1925 to 1936

"You are a Christian storm and you are in need of some of my paganism [...] I will go get you and give you some seaside medicine. It will be winter and we will light a fire. The poor beasts will be trembling with the cold. You will recall that you are an inventor of marvelous things and we will live together with a portrait machine..."

These are the passionate lines that Salvador Dalí wrote in the summer of 1928 to his close friend Federico García Lorca. Their relationship was something more than that, "an erotic, tragic love, out of the fact of not being able to share it," the painter himself would explain in 1986, in a letter to the editor published in EL PAÍS and meant for the Lorca historian Ian Gibson, whom he accused of underestimating his bond with the poet, "as though it had simply been a sugary sweet romantic novel."

The relationship between both geniuses lasted, with all its ups and downs, from 1923 to 1936 (the year of Lorca's execution at the onset of the Spanish Civil War). Besides the artistic partnership, the link gave rise to an intense exchange of letters that can now be read entirely, for the first time, in Querido Salvador, Querido Lorquito , a compilation by the journalist Víctor Fernández.

Fernández skillfully and meticulously gathered these letters, as well as the ones Lorca sent to the painter's father and sister, Ana María Dalí, and a woman named Lidia de Cadaqués, an extravagant character once described as "a paranoid erotomaniac" who served as inspiration for Dalí's "paranoid critical method."

It is not that many exchanges after all. Around 40 letters from Dalí to Lorca have survived. Only seven from Lorca to Dalí were preserved. Fernández has an explanation for this: " Cherchez la femme ." Or in this case, two women. "One is Ana María, who sold a lot of her brother's archival material after the Civil War; the other is Gala [Dalí's wife and muse], who destroyed many others out of jealousy. Among García Lorca's documents, there was a note that said: 'I don't like Gala.' Later it emerged that Lorca was an unwelcome topic at the Dalí household when Gala was around; the painter's papers include letters from Lorca that have been cut out with scissors; precious few people had access to those documents, and one of them was the painter's wife," explains Fernández.

One is trying to catch the artist in his spider’s web, the other lets it happen"

Behind all this, says the journalist, is the shadow of a homosexual impulse. The correspondence is "a game of seduction: Lorca is giving the best of himself, using his words to try to win over Dalí, who in turn wants to be at the same intellectual level as the poet. One is trying to catch the artist in his spider's web, the other lets it happen up to a certain point," says Fernández.

There is nothing explicit in the letters, not even a mention of a young woman named Margarita Manso, with whom Lorca had sexual relations at the request of Dalí, a voyeur at an encounter that the painter imposed as a condition to agree to relations with the poet. Yet García Lorca's sacrifice was useless because Dalí continued to resist, especially during Lorca's second stay in Cadaqués, in 1927, as the painter later revealed in a vulgar interview with Max Aub.

But the Surrealist painter knew he was attractive to the poet, and played with sexual references repeatedly. This is the case in a letter dated September 1928, written in the context of a piece of tough criticism from Dalí of Lorca's newly published Romancero gitano . Some scholars point to this letter as the beginning of the end of the relationship.

"There was no break, just a drift," says Fernández. The gap left behind was filled by Luis Buñuel, who was jealous in his own way and "acted as a sapper in that relationship." The filmmaker, who until then had had little intellectual and popular impact, would end up writing the script of Un chien andalou with Dalí. Lorca, who was from Andalusia, always felt the title was a reference to himself.

But after Lorca's death, he began to reappear in Dalí's drawings, explains Fernández, noting that each influenced the other's work. Lorca wrote Ode to Salvador Dalí , published in the journal Revista de Occidente . "Lorca never did anything like that for anyone else," the journalist notes. Meanwhile, Dalí allegedly reflected the poet in his paintings La academia neocubista ( Neo-cubist academy ) and La miel es más dulce que la sangre (Honey is sweeter than blood). And of course there is the play on which they collaborated together, Mariana Pineda .

Dalí always had the feeling that he might have been able to prevent Federico's death. "He felt he didn't insist enough to get him to come to Italy with him in 1936," says Fernández.

When Gala died in 1982, Dalí regressed mentally to his student days in Madrid, where he first met Lorca and Buñuel in 1923. In the end, when he was refusing to eat and was down to 34 kilograms, one of the nurses who cared for him said that in all the time he was in her care, she only understood one sentence that he said: "My friend Lorca."

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.