Minister saw light at end of the tunnel

New book outlines how Madrid owes its underground rail routes to Republic Public Works chief Indalecio Prieto's idea was met with ridicule at the time

The underground train line that finally opened up Madrid's blocked-up rail network toward the end of the Franco years owes its existence to the efforts of the public works minister in the Socialist government of the Second Republic, Indalecio Prieto, according to a new study.

In his recently published Indalecio Prieto y los enlaces ferroviarios de Madrid (or, Indalecio Prieto and Madrid's railway links), Antonio García Pérez lays out the details of a project that sank its roots into the minds of engineers, architects and technicians in the third decade of the 20th century. Both Prieto and Prime Minister Manuel Azaña were concerned about the obstacle that the mountains surrounding Madrid imposed on railway access to the city. The location of the so-called Estación del Norte at the bottom of the Cuesta de San Vicente - actually in the west of the city - determined that the lines went through the west and avoided the slopes that surrounded Madrid from the west round to the north and east. Atocha, the main railway hub for passenger and freight lines into the city, was in the capital's southeastern corner.

The development of Madrid was cut off by its own railway, which cut across the town, creating insurmountable urban barriers sprinkled with industrial areas close to the tracks to link them with freight routes, all with adverse effects for Madrid's population and economy. So Prieto and Azaña decided to circumvent it. Noting that the city was expanding toward the north of Madrid, along the axis of the Paseo de la Castellana thoroughfare, they decided to start planning the area. They arranged to move the main central government offices to the massive building in Nuevos Ministerios designed by Secundino Zuazo, which in 1929 already included plans for the Chamartín-Atocha underground rail route and a huge station beneath the Nuevos Ministerios complex.

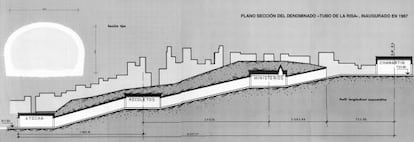

Prieto decided that the proposed underground route would connect Chamartín to Atocha by means of a link that took into account loop lines for freight trains, light-rail routes connecting to outlying residential areas and long-distance lines.

Resistance to the innovation led to the more reactionary sectors christening the idea the Tubo de la Risa (The Tube of Laughter), after a fairground ride of the day - a nickname that has stuck to this day. Nevertheless the Republican government maintained that the proposed infrastructure would satisfy the growth prospects of a populous and dynamic city like the Madrid of the time. They were not wrong, but it would be three decades before the project saw the light of day. The Civil War erupted and it wasn't until 1967 that the Chamartín-Atocha line finally opened.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.