If you want something changed, sign here

Single-issue campaign groups and online petitions have enjoyed exponential growth But is all this frenetic energy diminishing the opportunity to create a front against powers-that-be?

The usual procedure in grassroots organizing is as follows: find a cause that you think is worth fighting for, then create a website explaining the problem that needs solving and request online support. It could be anything: preventing a school from shutting down, fighting against the privatization of a water utility, or keeping a bus route running.

This type of informal civil association always champions very specific requests, and it is a very well-established system for effecting change in the United States. Elsewhere in the world, eroding confidence in the political class and a lack of institutional response to certain problems has made grassroots organizing suddenly popular, too.

In Spain, the leading example is the Mortgage Victims Platform (PAH), an association whose members stand to lose their homes to the bank, a situation that many jobless Spaniards find themselves in these days. Against all odds, this group managed to get the dramatic issue of home evictions on the congressional agenda, giving hope to others who feel that, just maybe, they too can make things change.

"We are seeing a proliferation of citizen groups," says Jesús Casquete, a professor of history of thought and social movements at the Basque Country University. "The most important reason is political parties' loss of credibility when it comes to finding solutions to people's problems."

We are tired of fighting for causes like hunger with no solution in sight"

Francisco Polo, director of the Spanish branch of the popular website Change.org, agrees. "A yawning gap has opened up between the political elite and the street. This is in addition to an erosion of trust in other institutions, like the unions. People feel that these are no longer working to defend their needs."

This rift between the leading classes and the people is made worse by the current economic and institutional crisis. "At times of recession, no one party is going to be able to satisfy the demands of citizens. Instead, they are forced to make cuts," says Manuel Jiménez, a sociology professor specializing in social movements at Seville's Pablo Olavide University.

The institutional disrepute, combined with government measures that rile voters, fuel the protest movement. "More and more groups will dare to do something to effect change," says Rafael Cruz, a professor at Madrid's Complutense University. Cruz believes that this year could see a rise in protests led by grassroots movements.

"In periods of recession it is normal to see momentary protests to preserve acquired rights. During times of economic expansion, it is more frequent to see long-range social movements to demand new rights," adds Professor Casquete.

The anti-eviction PAH is a turning point in terms of organization"

The rise and success of this type of organization is due, say the experts, to the fact that they support a specific cause (making the goal more accessible), that they are spontaneous (responding quickly to a given problem, compared with the slow response time of traditional organizations), and that they have a short lifespan (until they either solve the problem or fail to do so).

"People have gotten tired of fighting for big causes like hunger or poverty and seeing no solution in sight," explains Polo. "But these problems also manifest themselves locally in one's village, neighborhood or street. And that's where it's easier to effect change. For instance, people know that the environment is important. But the conservation of nature is a very broad cause. Yet if people come together to stop the construction of a large hotel in a protected beach and they manage to do so, then they see results."

Casquete agrees that it is easier to act on time- and place-specific causes like home evictions than on abstractions like the economic crisis in general.

"The anti-eviction group PAH was a turning point in terms of people organization. There is a before and an after. They proved that reality can be changed," says Polo. Jiménez adds that the secret to PAH's success lies in its dual activity. "They stop evictions; in other words, they solve an individual problem, and they have also made a place for themselves on the national political agenda, as an alternative to current legislation on housing policies."

It is a spontaneous group, and if the problem gets solved, we will disappear"

Jiménez adds that an essential factor in PAH's success is that it managed to "mobilize broad sectors of society which are not in principle directly affected by home evictions, but who might consider themselves morally affected, because they feel that an injustice is being done and they feel the moral obligation to act."

The PAH managed to collect over 1,400,000 signatures, with help from unions and other social organizations, to back what is known as a Popular Legislative Initiative (ILP) in Congress. Several parliamentary groups have already expressed support for the bill, which supports retroactive deed in lieu of foreclosure (handing over the keys to the house and walking away without being further indebted to the bank), a freeze on evictions and more subsidized rentals. But everything seems to indicate that the ruling conservatives of the Popular Party (PP) will use their absolute majority to prevent the bill from becoming a law.

Experts say that the most common occurrence is for these groups to remain at the local level. "It is easier to achieve changes because mayors are more sensitive to citizen demands. The political cost of ignoring them can be more immediate," says Jiménez. And even though the model is most commonly seen in the US, these days newspapers from all over the world are echoing micro-local petitions that sometimes take on national importance. But it is only when a conflict becomes generalized, such as the case of evictions, that success at the national level occurs.

People have realized that they can change things in their immediate surroundings, Polo explains. That is just what Antonio Vas thought. Vas is deputy president of the parent association of the Mérida Conservatory, a music center threatened with closure. Vas's group is asking the education department of the regional government of Extremadura to take over management of the conservatory as soon as possible - the way things stand, this will not happen for another six to seven years. Meanwhile, the city of Mérida has already stated that it lacks the money to keep the conservatory open.

Groups can go into hibernation mode, then return when a new problem arises

"We created a blog and began to drum up support," says Vas. In just a month they collected 10,000 signatures through street campaigns and the internet, and handed them over to the regional assembly on March 7. Even the famous soprano Ainhoa Arteta has supported the cause in a letter.

"It should make politicians stop and think," says Vas, who also turned to the ombudsman and met with other city representatives. "This is a spontaneous group, and if the problem gets solved, we will disappear," he adds. This transitory nature is, in fact, one of the chief characteristics of grassroots organizations. It happened with the groups that formed to fight the closure of night-time health emergency services in Tembleque, a small municipality in Castilla-La Mancha.

"When a decision is consolidated, either to close down the services or to keep them open, then these groups lose their raison d'être," says Jesús Casquete, the Basque university researcher.

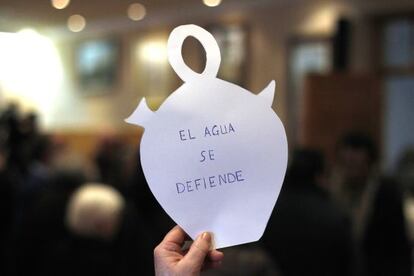

But occasionally, these groups go into hibernation mode, then come together again when a new problem arises in their field of expertise. A case in point is the group against real estate speculation in Candeleda, a village in southern Ávila. A few of its 5,000 residents got organized in late 2006 to halt construction of a large residential estate with over 400 homes. They finally got their way, but not before going to court. "It would have been a catastrophe for the village's environment," says Pilar Diego, one of the group leaders. Then in January of this year, the organization got together again to stop plans to privatize the water utility despite widespread protest from local residents. "Protesting is hard work, but those of us who get involved can no longer look the other way," Diego adds.

A lot of people complain over their coffee," says the art scholar Casado

This type of proactive attitude towards problems is what Antonio Casado, head of the library at Castilla-La Mancha University and art history scholar, prizes most highly. "A lot of people complain over coffee, but they do nothing about it," he says. Last January, when he found out that Castilla-La Mancha regional premier María Dolores de Cospedal supported the city of Toledo's decision to move the National Museum of El Greco to the provincial museum of Santa Sofía, he did not hesitate to create a grassroots organization to stop it.

"This made me particularly angry," he recalls. "I talked it over with friends, history professors and city artists, and some of us figured that this decision was barbaric. It means wasting the six million euros that were invested in refitting the El Greco museum. And the paintings would lose context."

The group against the transfer of the El Greco museum was born on March 6, and the first things it did was create a blog, open accounts on social media to spread the message and start a petition to collect signatures. Their demand has already gained support from neighborhood associations, businesspeople and former city mayors. "Now we will start knocking on politicians' doors, to see whether they will hear us out," says Casado.

Traditional protest methods - street demonstrations, sit-ins or petitions - now combine with the power of new technology to multiply their points of pressure and their chances of success. Polo, chief of Spain's Change.org, has seen a rise in the quantity and quality of web petitions. "At first people didn't know how to make a petition," he says. "They have to be short, clear messages expressing what one wants to change and why." But these days, users need fewer guidelines. The website registers over 1,000 petitions a month, the company says. "Many end in victory. That's almost one victory a day," says the site's director, himself a former Socialist party activist.

This is wasting the six million euros invested in the El Greco museum"

These websites reflect petitions from large organizations like Amnesty International or the Red Cross, but also from any angry citizen. "With the internet, people no longer have barriers to becoming leaders of change and can mount a campaign without a lot of money," adds Polo. But some users say the websites are useful not just to raise awareness about their problem, but also to collect enough signatures to pressure the person in charge of a decision, since every show of support translates into an email sent to the person in question.

In a way, information technologies eliminate the need for formal organizations to coordinate action, says Jiménez. These days, supporting a cause is as easy as a click of the mouse, with no need for membership cards or attending meetings. This in turn raises questions about the legitimacy of some demands that lack any known association behind it. It is frequent to see petitions for one thing and for the exact contrary arise at the same time, notes Polo. Which is the correct choice? "It is up to citizens to decide whether they support a change or not," says Polo. "It is fantastic to see people participating beyond the vote every four years. That's what being a citizen is all about."

But some people think that this explosion of groups and petitions is destroying the chance of a united front against the established political class. If each group of citizens fights for its own cause, then efforts get diluted. To prevent this, last summer José Luis Rodríguez decided to bring all these citizen initiatives together into one umbrella group, - plataformaciudadanaya - a solid bloc able to face down bipartisan politics during elections. "We don't want to be just another group that serves to create greater separation," he says. "Instead of saying 'join us' we're saying 'let's all join together.' His only tools are a blog, a website and a Twitter account.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.