Female pioneers in the literary adventure

Spain's national library attempts to atone for its own discriminatory past with a major exhibition on the women who broke down the book world's barriers

Teresa of Ávila, the saint and mystic, also believed in being frank about her feelings. At the beginning of her seminal book Camino de perfección (The Way of Perfection), written for her community of nuns - the Carmelites, which she discalced and guided down the path of austerity (Angela Merkel would have liked her: a southern woman with a northern spirit) - Saint Teresa confesses her profound weariness: "There are few things which obedience has dictated to me that I find so arduous as writing now about issues of prayer."

The nun's head had been filled with a stormy sound for the last three months, and she felt "weak." This confession to her sisters can be read by anyone who visits the exhibition El despertar de la escritura femenina en lengua castellana (or, The awakening of women's writing in the Castilian language), at Biblioteca Nacional.

The national library is honoring literary pioneers who lived in historical times that did not look kindly upon writers who were not born male.

Things have changed, of course, but not too fast. This very institution was for a long time off limits to women. "The Biblioteca Nacional has a very sexist tradition behind it," says library director Glòria Pérez-Salmerón. "[King] Felipe V only allowed men inside, and women were unable to visit the premises until 1837, and then only on Saturdays." In fact, it was not until 1990 that Biblioteca Nacional finally had a woman director (Alicia Girón), and it was certainly not for lack of candidates.

The exhibition will partly atone for this past. Some 40 books, culled from the library's extensive archives and selected by curator Clara Janés, a poet and women's writing scholar, prove that adversity is not always an insurmountable obstacle. Going against the tide has always been an option for some.

Cristobalina Fernández de Alarcón would often anger the famous writers Quevedo and Góngora - whose conceit was as enormous as their talent - because she routinely won all the poetry competitions that she entered. Lope de Vega loved her, though. Lope liked women - in a specific and in a broad sense. During a speech he gave in Madrid he expressed joy "to see that a woman could accomplish so much that, discalced, she built a giant's career within the militant church" - that of Saint Teresa. The curator of the show notes that Lope paid tribute to many other female authors of his time in his own works.

Lope's own daughter occupies a prominent position within the exhibition. Sor Marcela de San Félix joined the Trinitary sisters, whose convent was just one step away from the family home. "They say that Lope went to see her every day," explains Janés. Sor Marcela was one of the very few female authors to choose theater as a form of expression (she had genetics working in her favor), although her plays were performed within the convent walls and always versed on religious topics.

Poetry was the preferred genre for most women, although they tried their hand at everything, from essays to novels and scientific papers. Little is known about María de Zayas y Sotomayor, even though she was a prolific writer. Her Novelas amorosas y ejemplares (Amorous and exemplary novels) were published and translated on 14 occasions between the 17th and 18th centuries, and the work is known as "the Spanish Decameron." On one occasion she said that "souls are neither men nor women."

While it has been insinuated that María de Zayas y Sotomayor was actually a man, Clara Janés rejects this hypothesis. "She concealed herself well, probably because she was a noblewoman and felt she would be in danger if her identity were to be revealed." De Zayas was a feminist back when there was no such thing as feminism, just bold women who challenged the norms.

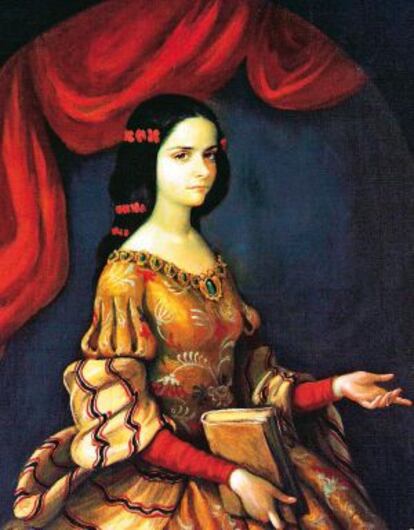

But the most important feminist of all was Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who was born in modern-day Mexico in the 17th century but thought like a 20th-century woman. A voracious reader, she fantasized about going to university disguised as a man until her family put a stop to her plans by introducing her into the court of the Marchioness of Mancera, wife of the Spanish viceroy.

Juana Inés had talent, intelligence, looks and an aversion to marriage. She was given the only option there was at the time: taking her vows and entering a monastery. The hyeronimite nuns gave her the freedom she needed: she kept her scientific instruments, her books, her clothes and her maids. She defended women's right to education. She invigorated intellectual debate so much that following her Carta Atenagórica , she was persecuted and punished by Church leaders, who forced her to renounce everything she had ("I, the worst of all women" she wrote in penance).

The Inquisition effectively dealt with them all, beginning with Saint Teresa of Ávila and continuing with her disciples Ana de Jesús and Ana of San Bartolomé, who both fled to Belgium. Even for someone like Clara Janés, who has been exploring the history of female writers for years, Biblioteca Nacional concealed surprises like the work of Sor María de la Antigua, a nun from Seville who left over 1,300 notebooks behind. She is the only sister who appears in a drawing next to the discipline -- a hemp whip used for self-punishment -- in the collection of illustrations also on display.

Were nuns the only women who wrote? No, says Janés, but convents were the only refuge for those restless minds who were born in oppressive times, and the only places that preserved their writings.

El despertar de la escritura femenina en la lengua castellana . Until April 21 at Biblioteca Nacional, Paseo de Recoletos 20-22, Madrid.www.bne.es

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.