Learning to drive the long way

Frustrated by the monopoly of driving schools, Gabriel Lucas went it alone

There is nothing odd about a 30-year-old man getting his driver's license. But Gabriel Lucas, a computer engineer from Madrid, happens to be the first Spaniard to obtain it without going through a driving school first - at least since 1981, when a legislative reform made it harder to do so.

It took him four years of research and red tape to obtain his license through self-study, not to mention a total cost of 2,500 euros compared with the average 740 euros that people spend on driving lessons.

Lucas even had to adapt his car, which now has six pedals (three on the passenger side), as well as convince his mother to act as his driving instructor.

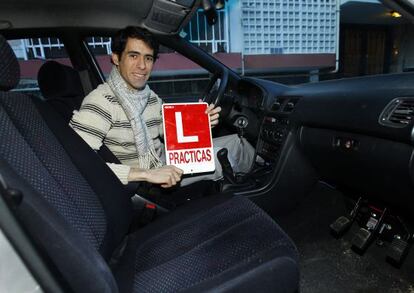

Now he looks back affectionately on the long journey that ended last November, when he finally obtained his prized 'L' learner's sign to display in his rear window for his year at the wheel - only after that will he be considered a fully fledged driver.

The requirements for taking a driving test without going through a driving school first include getting a car fitted with three extra pedals

For Lucas it was a matter of principle, not money. "I disagree with the fact that a common good such as learning how to drive is being monopolized," he explains. "I think you have to be consistent. If you want to change something, why not do it?"

The requirements for taking a driving test without going through a driving school first include getting a car fitted with three extra pedals and two rearview mirrors on the passenger side, so the instructor will have control of the vehicle; insuring the specially fitted car for the purpose of training; and finding someone who has had a license for over five years and not received a traffic violation for the last three years to act as your instructor.

Lucas knew nothing of this at age 19 when he signed up for regular driving lessons "like just about every other youngster." But he fell ill, and was unable to attend class for seven months. When he went back, his enrollment fee had expired and the school wanted him to pay again.

But Lucas did not have the money, and he dropped his plans to drive. Until four years ago, that is, when he began toying with the idea of taking the unconventional route. Not even the employees at the DGT traffic authority were able to help him until he showed up with the law in his hand. He had discovered the relevant legislation on an internet blog.

Lucas installed a dashboard camera to document the process

But after passing the written test ("it was relatively easy"), the real trial began. Lucas decided to take things easy. The 1998 Honda Accord that his uncle gave him as a gift became his new ally. He took it to an auto repair shop and got the extra pedals fitted. But finding a company willing to insure it was harder. Aware of the difficulties, he wrote to his own insurer and informed it he was planning to do driving practice with that car. The company was not interested. Five other insurers also turned him down.

That was when he discovered Consorcio de Compensación de Seguros, a public institution that accepts cases rejected by the private sector. "All I had to do was show up with two letters proving that my case had been turned down. That, and convincing my father to sign the insurance papers. 'Why can't you do things like normal people do?' he asked me. He thought it was all too weird. But in the end he agreed." By then, though, it had been too long since he'd passed the written test, which he eventually had to take twice more. All the while, he was looking for someone with a spotless driving record to act as his instructor.

"How do you find out if the people around you have been fined?" he asked himself. A friend of his could not do it because "he'd once parked on a street corner and been fined."

In the end, Lucas turned to his own mother. The DGT gave them a permit and an eight-month time limit for the in-car driving practice.

As though they were playing a video game, the pair proceeded by levels of difficulty: first, driving in a closed circuit (a university parking lot on a weekend); then, driving through Majadahonda, a residential suburb of Madrid; later came the more complicated routes.

Lucas even installed a camera on the dashboard to document the entire process, which he has been telling the world about on his blog.

Finally, the big day of the road test arrived. And, like so many other applicants, he failed on his first attempt. "I got nervous when they asked me to park," he recalls.

After that, he and his mother spent an entire weekend parking "in all possible ways."

In the end, it was down to the wire: on the day his special DGT training permit expired, which is only issued once, Lucas passed the road test.

Now, he wonders why his case should be so exceptional.

"Before 1981, the DGT used to loan out cars, which made it easier to get your driver's license without going through a driving school," he says. "Now the business is monopolized, and they even set prices, around 30 euros for 45 minutes of driving practice."

The National Driving School Confederation recommends that all applicants go through a school in order to receive "the kind of experience and training that only a driving instructor can provide."

Lucas does not claim they are wrong, and admits that his own driving style mirrors that of his mother, which is why he hired a professional driving instructor to give him two lessons right before the road test.

"The goal is to drive well, to create good habits," he says. "I know a lot of people who boast about the fact that they took very few lessons. I drove for many hours and went into the test feeling very self-confident. In the end, that's what it's all about."

So now what? For now, the truth is he does not do much driving at all. His Honda Accord is parked in Majadahonda, at his parents' house, while he lives in downtown Madrid, "where you don't need a car."

Besides that, he hates the pollution that cars cause.

But his initiative may encourage one of his three younger siblings - or 15 cousins - to follow in his footsteps. The car is there for any one of them to practice in.

Lucas, who works as a computer engineer for the city of Madrid, wants to see some legislative changes. That is why he created a forum that he hopes will generate a public debate on the way that Spaniards obtain their driver's licenses.

In the meantime, his next goal is to create a driving manual that would be available for free and "less boring" than the one offered at schools. "It took me so long to pass the written test because I kept falling asleep in front of the book," he recalls.

Eventually, he would like the whole experience of getting a driving license to be less "traumatic" than it is for a lot of people these days. He is already driving towards that goal.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.