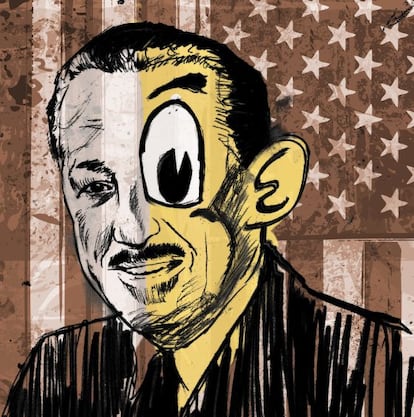

From Mickey Mouse to the opera house

Composer Philip Glass is bringing the dark side of Walt Disney to the Madrid stage

He was a misogynist, a racist, an adulterer and a megalomaniac with a fascist side... Such is the dark personality of Walter Elias Disney that writer Peter Stephan Jungk portrays in The Perfect American, a fictionalized biography of the Mickey Mouse creator that has been turned into an opera by the composer Philip Glass and is set to receive its world premiere at Madrid's Teatro Real on January 22.

The story - "built on many biographies and some elements of fiction" - reflects the uglier aspects of the founder of the Disney empire through the eyes of a disgruntled ex-employee.

Opera director Gerard Mortier commissioned the work from Glass when he was working at the New York Opera, though the production never premiered there.

The well-known composer of minimalist music had never been faced with a story about a fellow American, and he was manifestly afraid of participating in a project that made the leader of the powerful Disney corporation look bad. "He feared the Disney factory," summed up Mortier.

I see Walt Disney as an icon of modernity," says Philip Glass

As a result, there was constant tension throughout the project over just how to reflect the novel's harshness. "When I started out, people thought I was going to laugh at him," says Glass. "But I see Walt Disney as an icon of modernity, a man able to build bridges between highbrow culture and popular culture; just like Leonard Bernstein, who could jump from a Broadway musical to a Mahler cycle."

Then came the call from the Disney studios. "We would rather you didn't do this," he was told. But there was no going back. So Glass found himself a trusted librettist and a first version of the novel was translated into opera form. The libretto was sent to the Disney studios and there was no reply.

"That means a green light," recalls Jungk, the writer of the source novel.

Meanwhile, Mortier was busy trying to prevent The Perfect American from being watered down and to preserve the darkness of a character who was obsessed with his kingdom and the possibility of its disappearance once he died. "He reminds me of Cocteau and his Orpheus because of this notion of immortality," says Glass.

Walt Disney endured a terrible childhood growing up on a farm in Marceline, Missouri. Raised in an environment that seemed taken right out of a William Faulkner novel, including a strict father who often enforced corporal punishment, he was made "of the stuff of great Americans like Henry Ford or Thomas Edison," as the fictionalized Disney himself says in the book.

And therein lies the perfect balance of the story. Disney was a genius, but also, posits the novel, a ruthless hypocrite who turned in Charlie Chaplin during the Communist witch hunt even though he admitted that Chaplin was the main inspiration for his imaginary kingdom. He was a self-made man who embodied the rags-to-riches myth, yet was also deeply resentful of the working class (even though his father was a Socialist) as a result of the 1941 cartoonist strike at his studios.

The main characters in the opera are Wilhelm Dantine, a former studio employee who becomes Disney's nemesis, and even shares the same initials; Hazel George, Disney's masseuse and lover; Disney's wife Lillian; Andy Warhol, who identifies deeply with Disney; and an Abraham Lincoln robot at the Disneyland theme park in Anaheim, California, which in both the novel and the opera has a wonderful exchange with the mogul in which the latter expresses admiration for Lincoln but also notes the deep discrepancies dividing them that oblige him to shut the machine off.

"You feel a marked sympathy for blacks, now there's something we cannot agree on," says Disney in the novel, questioning the abolition of slavery. "Was the Black Panthers what you wanted? Martin Luther King?" According to the novel, Disney did not allow African Americans to work for him and refused boxer Muhammad Ali entry to his theme park.

Obsessed with science and the possibility of cryogenization, the opera ends with Disney's cremation - nobody in his family respected his last wishes. He had become the one thing he feared: a company. When he learned that his lung cancer would let him live another two years at the most - he smoked three packs of Lucky Strikes a day - his brother told the doctor: "Two years? He's got work built up for a lot longer than that." The exploiter had become the exploited. He was a man who built a matchless empire with the inestimable help of anonymous workers, who only allowed his female employees to color in the cartoons. He was a perfect American who did not do any of the actual work for which he became so famous - even his trademark signature, reproduced time and again, was done by someone else.

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.